| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 5/17/2024 Occurred: 2/3/2003 |

Page Views: 1511 | |

| Topics: #18-Wheeler #TruckDriving #BigRigs #Schneider #TruckDriver | |||

| An entry from Alternate Roads: Paul S. Cilwa's Truck Drivin' Journal | |||

Monday, February 3, 2003

According to my log book, my current assignment started early this morning, about 1:30 AM, after my eight-hour DOT break. I actually received the assignment yesterday, after I picked up a trailer in Riverside, California, that turned out to be overweight. I left it at the Fontana Operating Center for them to deal with. Another assignment quickly came in: I was to bobtail to San Diego and pick up a trailer for Disney On Ice.

My first thought, of course, was that I was picking up Walt Disney's frozen corpse and moving it to another location. You may have heard the persistent rumor that Disney had himself dunked in liquid nitrogen at his death, thus freezing his body for eventual thawing and, presumably, revivification. The Disney estate has denied this rumor so energetically that it must be true!

But, no; this was an ice skating show at the San Diego Sports Arena with a Disney character theme. They were about to do their last show in San Diego and I was to assist in moving the props, costumes, and skates to their next venue in Sacramento, 510 miles away.

San Diego is about four hours from Fontana; Sacramento is ten hours' drive by truck from San Diego. So the only way I could legally perform this assignment was to sneak an eight-hour DOT break in between driving to San Diego and driving to Sacramento. (Did I mention the assignment specified a noon delivery? The next day?) In order to do this, I needed to arrive in San Diego by 2 PM for the 10:30 PM loading. Unfortunately, I received the assignment at 2:30 PM. I actually got to the arena at 6 PM. But, according to my log book, I got there at 4 PM, which meant my break would be over at midnight.

Now, you would think I would be unable to get away with this. Doesn't the truck's onboard computer know when I move the truck? If I loaded at 10:30, as I was supposed to, wouldn't the onboard computer complain that I had violated my break?

Well, yes and no. In theory, yes. However, I have discovered in the last few weeks that if I move only a short distance, say, across a parking lot, in reverse or first gear, the onboard computer doesn't seem to register it as moving at all. So, when I was coupled to the Disney On Ice trailer, I was careful to move slowly, in reverse, backing it into the arena's loading dock. And then, when the loading was done, I returned to my spot in the parking lot and shut down until 1:30 AM. I slept between 6 and 10:30, and between the conclusion of loading and 1:30. I wasn't as rested as I would have preferred, but I needed these miles.

Think of it as a magic trick. The important thing is, does it work? Not, how did it happen?

This was not my first brush with show business. Actually, my first stage experience should have scarred me for life. I was in kindergarten in New Jersey. (We have moved so many times, I associate the milestones of my life with the town and house I lived in when they happened.) Christmas was coming up, and the kindergarten was to form an orchestra, made up mostly of triangles, whistles, and drums, and Mother Superior had decided I would be the conductor.

Mother Superior was the principal of the Catholic grade school, and she was very intimidating, to the kids and the other nuns alike. My knowledge of English wasn't yet developed enough to wonder if there was a Mother Inferior and, if so, what was her job at the school? Did she also intimidate others or was she intimidated by them? Of course, I didn't know the word intimidate either. I just knew Mother Superior scared the pants off me.

Since I also didn't know what an orchestra conductor was or did, Mother

Superior had to show me. She had me hold a foot long baton in my right hand, and

stooped so close behind me I could feel her breath on my neck. She then enfolded

my right hand in hers, and forced me to waggle the stick in a rectangular

pattern. Just make a square in the air with the point,

she said.

Unfortunately, I didn't know what a square was, yet, either; and the

shape she was trying to describe in the air didn't seem to be much of anything.

I tried to anticipate where the baton would go next, but it was never where she

wanted it to go. As we wrestled for control of the baton, she struck me in the

nose with it, hard enough to make me cry. She fired me on the spot, telling my

mother later that I had an attitude

.

I felt far worse than I would have if I had never been asked to conduct the orchestra in the first place.

I don't feel that I have a particularly large nose, but the incident with Mother Superior wasn't the only time it got me into trouble.

We had moved to rural Vermont when I was in second grade; my father died a few months later. By the time I was in fourth grade, I had made some friends, not the least of whom was my teacher, Mrs. Howe. Mrs. Howe and I shared a love of books and stories and bonded, in spite of the fact that I could never seem to get my arithmetic homework completed on time. She didn't let me get away with it; she simply prepared a list of the assignments I had missed and allowed me to get them done and turn them in late, which I thought was eminently fair and practical. After all, it wasn't like I intentionally neglected my arithmetic. It's just that I spent so much time writing stories for English class, that there wasn't adequate time left for other subjects.

I bring this up to point out that I liked school. I have to point this out because I missed an awful lot of it.

According to my mother, I had allergies

. Certainly my nose ran a lot and I

often had a sore throat. In the late fifties, it never occurred to anyone that I

might be allergic

to my mother's smoking. She didn't smoke that much, but we

now know the poisons linger in the home atmosphere for hours and hours. She

tried taking me to Arizona, and later we moved to Florida, but my allergies

persisted. In fact, in Florida, where my cigarette-smoking grandparents moved in

with us, they got even worse.

But, in addition to my nose running, I hated to get up in the morning. This was probably because I had been reading in my bedroom, with a flashlight, under my covers, long after I was supposed to be asleep. But every morning was like hell. I discovered that I could make myself sick enough that Mom would let me stay home. By the time the school bus had come and gone, I would finally feel better. But then, of course, it was too late to go to school.

I missed so much school that the truant officer came to the house one day. And so, the next time I told Mom I was too sick to go to school, she countered that I would have to go to the doctor's—I couldn't just stay home. School or the doctor's; pick one.

I picked the doctor.

The doctor we went to see was Dr. Dixon. I don't know why we still saw him.

He was the man who had misdiagnosed my father's brain tumor as high blood

pressure.

But Mom has always been reluctant to change doctors. When we later

moved to Florida, she saw the first doctor she had an appointment with, Dr.

DeVito, for decades. In addition to being a general practitioner, Dr. DeVito was

the town's leading cardiologist, and Mom continued to see him until he died of a

heart attack in 1984. So it shouldn't be that surprising that we showed up at the

office of Dr. Dixon with my running nose.

Dr. Dixon was old and cranky, with stringy white hair and watery blue eyes that looked like there should be goldfish living in them. He listened to my mother describe my symptoms—he was the kind of doctor who preferred not to deal with the actual patient if it could be avoided—and reached for a little plastic bottle of nasal decongestant, such as you might see advertised on The Lawrence Welk Show along with preparations for the relief of hemorrhoids and irregularity. It was about one quarter full, and I wondered how he cleaned the nozzle between patients—because, obviously, I was not the first to receive this treatment.

He told me to hold my head back, and rammed the nozzle into my left nostril

and squeezed. Instantly, a wet, burning sensation filled my head. But before I

could react, he retracted the nozzle, jammed it into my right nostril, and

repeated the procedure. There!

he cried in triumph. My head was stuffier than

ever, but he seemed to feel he had accomplished something.

He turned his back to me for a moment, then turned back, holding a large

needle. Since you aren't in school today, you'll miss your DTP vaccination this

afternoon. We may as get it over with now.

My breath caught in my throat. I

hated vaccinations. My heart pounded and I looked for escape, but there was

no way out. He swabbed my upper arm roughly with alcohol, then jabbed the needle

into it with all the delicacy of a trunk falling downstairs. I caught my breath,

and the nasal decongestant suddenly started working. I sneezed, a great gob of a

sneeze, loops of freed mucous flying through the air and landing on Dr. Dixon's

white coat and sleeve.

He glared at me. Mom hadn't really noticed; I think she looked away when he

came at me with the needle. I thought the ordeal was over, but it wasn't. The

next day, when I walked into my classroom at school a few minutes late, there

was a sudden hush. The students all stared at me. What?

I asked. The kids all

started talking at once, but Mrs. Howe silenced them by holding out her palm.

Let's let Paul tell his side of the story,

she said firmly.

What story?

I asked.

Dr. Dixon was here yesterday afternoon for vaccinations,

she explained. He

told some of the students that you spit on him.

What??!

I was speechless.

Why don't you tell us what really happened?

Mrs. Howe encouraged.

So I did. I had to think first, because I did not associate sneezing and

spitting. But, when I was done, Mrs. Howe beamed. See?

she said. I knew

there was an explanation.

I will always marvel at the way Mrs. Howe never made up her mind on the basis of one person's story—even when that one person was an adult, in a highly-respected profession, and the other was a little kid. All I know is, without her fair treatment of me, I might have been so warped by the looks of disgust from the kids as I stood there, in the front of the classroom, still wearing my coat and holding my books, that I might never have been able to stand before a group of my peers again.

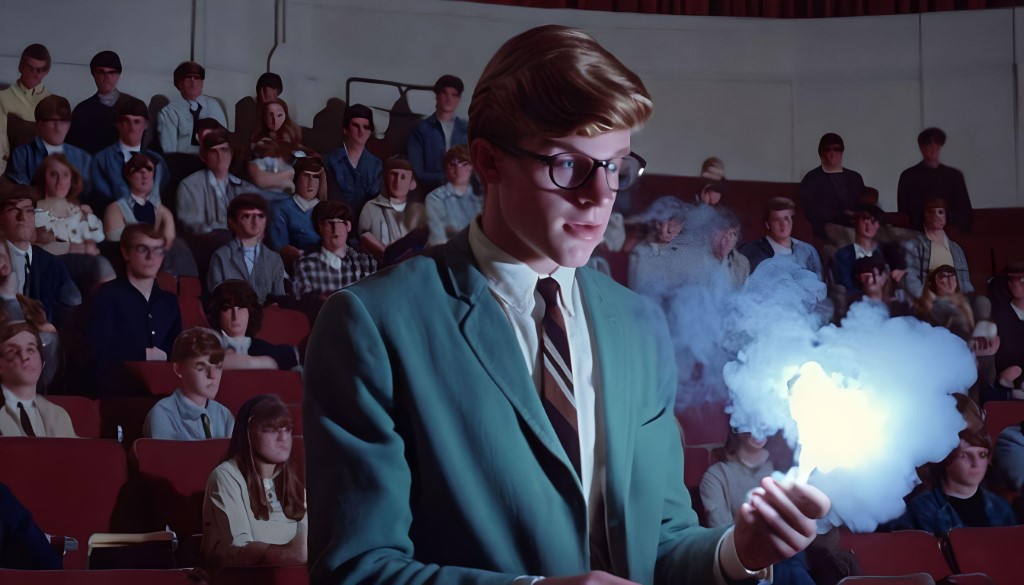

As it was, I didn't get the nerve to perform publicly until I was a sophomore in high school. By now, we lived in St. Augustine, Florida and I attended St. Joseph Academy. Sister Concepta, one of my teachers, decided a talent show would be fun and actually asked me to sign up for it. I took a deep breath and did so, even though I had no idea what talent I would try to display. I have no idea what talent Sister Concepta thought I had. She taught science and English, and she and I had had a major disagreement on Shakespeare—I had dared to criticize one of his plays. My only other experience with her was in running the school's movie projector—I was the only person in the entire school, student or faculty, who knew how—but I could hardly do that in a talent show.

Inspired by the fact that she taught senior chemistry, I turned to an old

friend: the Encyclopedia Americana in the local Public Library. I had discovered the encyclopedia in

grade school. What a find! In a single volume, one might

learn about carvings or George Washington Carver; about flintlocks or Douglas

Fairbanks, Jr. In the C

volume, I discovered chemical magic

, a subheading of

chemicals.

I knew about chemicals from comic books, but I thought one had to be from

Krypton or an arch-villain to obtain them. This article explained that certain

chemicals could be obtained from my local pharmacist, and gave a number of

examples of visually-impressive chemical feats, along with sample patter

the

chemical magician could employ as part of the act. In those pre-Xerox days, I

hand wrote the list of ingredients and notes on patter and went to the drug store.

What I haven't mentioned yet, is that I did all this the day of the talent

show. The article insisted that the magician practice the tricks at home,

first, which seemed like a good idea; unfortunately, I just didn't have the

time. I decided to practice with just one trick, the one that seemed most

unlikely to me: the Flaming Water.

The idea was to take one part rubbing alcohol, and three parts water, and put

the mixture in a large glass bowl so that everyone could see it was filled with

clear liquid. Everyone knows that water doesn't burn,

the magician was to say,

but let's test that theory.

The magician was to dunk a white handkerchief in

the liquid, then light a match to it and feign dismay when the handkerchief lit

on fire.

As I suspected, this trick was lame. The cloth did light on fire, but it was a very anemic flame—one that could not be seen past the first row, I was sure. My Mom had loaded my sisters into the car and was calling me to go as I tried increasing the percentage of alcohol. I went for equal parts, dunking and lighting. The flame was a little more pronounced, but still pretty faint. With Mom yelling that we were going to be late, and what kind of impression would that make, I made a last stab, going for one part water and three parts alcohol. The flame was much brighter, but still not very impressive. Still, I was out of time. I gathered up the ingredients and props and ran to the car.

We did arrive in time. Participants were to sit in the audience until the act before theirs began. I listened to classmates sing, watch them dance, even heard my Boy Scout pal Ricky Martin's band, although neither he nor his band mates attended my school and I couldn't figure out how he'd gotten invited to perform. The nuns must have really been desperate, I decided, which also explained why they'd asked me.

Finally, it was my turn to go backstage. I stood there, sweating, heart

pounding. What had I been thinking? I wondered. Obviously I had suffered

momentary insanity, agreeing to do this show, and now I would pay for it. If my

hands didn't stop shaking, I thought, I would never be able to handle the props.

Obviously, this was what people called stage fright.

I wondered if it was ever

fatal.

Then I was being pushed onto the stage of our old auditorium. I stood there, looking out at a capacity audience. That's not saying much; the school building was well over a hundred years old and the seats were old, folding wooden affairs that were fundamentally uncomfortable, so the people standing might have been doing so out of comfort rather than necessity. Still, looking out over this crowd—my teachers, my family, even Dr. DeVito (whose kids attended the school)—I was at once filled with a sense of power and of dread.

I remembered reading that, to overcome stage fright, all one had to do was look out over the audience and imagine them naked. I tried it. It didn't help. Actually, the thought of the nuns naked made me a bit queasy. I quickly mentally re-clothed everyone, though while doing it I did mentally create better outfits for some of the girls.

I'm going to show you some of the wonder of chemicals,

I said, amazed that

my voice actually came out. It quavered a little, but people seemed able to hear

it. I had brought my notes with me and placed them on the floor by my feet. I

suppose the audience wondered why I was looking at the floor so much, but I

found that once I reminded myself of a particular trick, doing it was

relatively easy. I announced I would begin by washing my hands with soap and

water. It wasn't really water and the bar of soap had been pre-treated, but the

audience didn't know that. My hands turned cobalt blue and I did a double-take,

about as subtle as Lucy Ricardo might make, at the results. The audience

laughed, and I looked out at them, startled.

Were they making fun of me? Laughing at me?

No. They seemed to be enjoying themselves. I had made them laugh, intentionally. They were in my power!

It was an amazing, overwhelming, emotion. I could hardly believe it. I felt like a super-hero. Good Humor Man, I thought. Able to leap over tough audiences with a single punch line.

Milking the joke, I wiped my brow with my chemically treated hand, leaving a

blue streak across it. The audience howled, and I took on a pained look.

Please!

I said in mock seriousness. Chemicals are a serious subject!

That

wasn't in the notes. I made it up on the spot, and the audience loved it.

I took off my glasses and glared at them. Look at this!

I cried. That last

demonstration didn't do so well, and now there is blue stuff on my glasses. I

shall have to clean them.

The stilted grammar had been in the notes, but the

audience seemed to enjoy that, too. I dipped the handkerchief in the clear

liquid and wiped my glasses with it. Immediately they were covered with a thick,

brown goo that glopped onto the floor. I made a face and recoiled, as if afraid

the stuff would get on me. The audience howled with glee.

As the laughter died down, I put my glasses on the table, ready for the piéce de resistance. Clearly I could have entertained this mob for hours, but my time was limited. I just hoped the flaming handkerchief would be visible enough to the people in the back to make a good finish to the act. On the spur of the moment, I thought—what the heck? Three parts alcohol to one part water had been almost good enough.

I filled the bowl with pure alcohol.

The other demonstrations haven't gone too well,

I said in mock misery. But

this is simple enough. It cannot fail. We all know water won't burn. All

we have to do is prove it.

I picked up a fresh handkerchief with a pair

of tongs and dipped it in the clear liquid. I lit a kitchen match. I held it to

the handkerchief for just a moment.

There was a foof! sound as the handkerchief caught fire. A pillar of flame leaped into the air, all the way to the curtain at the top of the proscenium arch above my head.

Dr. DeVito, in the back row, leaped to his feet. My God!

he cried. He's

setting the theatre on fire!

Suddenly aware that such a cry might well cause a

stampede, and not wanting to be at the tail end of one, he ran to the end of his

row, stepping over the people seated there, and out of the auditorium. Several

other people fled as well, but most, mercifully, did not. People in St.

Augustine, as a rule, were not an excitable bunch. A few years later, when the

mayor's ex-wife was hatchet murdered, people agreed it was a shame but not worth

missing their soaps over. So I had a few moments in which not

to complete setting the school on fire.

I lowered the tongs almost to the floor. The flame still rose ten feet into the air, but no longer touched the curtain; and I knew from the encyclopedia that alcohol does not make a very hot flame, though I could certainly feel the heat from this one. I did not believe there was any real danger as long as the flame didn't remain in contact with the curtain. I did not have to feign dismay, however. My dismay was quite genuine.

However, after the first moments of Dr. DeVito's panicky exit, when it became apparent to everyone that this was just another magic trick, the audience as one began to applaud, loudly and enthusiastically.

Except for Sister Concepta, who taught chemistry, and whose dismayed expression mirrored my own.

When the flame finally died out, I said apologetically to the audience,

Well, that concludes my chemical demonstration. I will now leave…if I can

find my way out.

I put on my glasses, still covered with the brownish goo, and

staggered off, stage right.

When I removed the glasses, I found myself staring at Sister Concepta. No

more chemicals next year,

she hissed.

Looking back, I'd have to say my second foray into show business was, in

spite of a near disaster, pretty successful. Even, considering that it was

flaming,

prophetic. And now, here I am, years later, a gay truck driver and

still managing, in a small way, to contribute to the entertainment of the masses.

Show business.

There's no business like it, I'm told.