| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 7/27/2024 Occurred: 6/26/1994 |

Page Views: 1266 | |

| Topics: #Rafting #WhitewaterRafting #PenobscotRiver #Maine | |||

| Whitewater rafting and camping trip on Maine's Penobscot River with the kids. Photos and text. | |||

Or, How to Drown the Kids

In June of 1994, I decided to take all the kids rafting.

This was quite a job; by this time, none of the kids lived with me…or, even, in the same state as me.

I wanted to do the rafting trip right, so I started with a travel agency-style flyer for "Cilwa Adventure Travel" and a schedule. I wanted to get the kids excited about the trip so they could enjoy the anticipation. I also wanted to convince the parents of John’s girlfriend at the time, Rachel, that she would be in good hands.

Originally, I planned to bring Dottie and her boyfriend (called "Slow Mo"), Karen and her boyfriend, DJ, Jenny and her boyfriend, Jimmy, and John and his girlfriend, Rachel. However, as soon as I had arranged for the tickets, Dottie and Slow broke up, as did Karen and DJ and Jenny and Jimmy! I was not pleased, but of course I couldn’t expect them to continue dating people they no longer liked just to accommodate my schedule. So there were some last-minute adjustments. Dottie brought her new boyfriend, Critter (honest, I don’t make these names up) and Karen and Jenny did not bring dates. This actually worked out for the best because I had arranged to rent a van for the trip and it would have been a bit crowded if the original group had all come.

Since I had by now rafted Maine’s Kennebec River twice (once with Dottie and twice with John), I wanted to "do" something different. After studying the brochures, I settled on the Penobscot River, which is run near Maine’s Baxter State Park. The drive time from Manchester, NH (where I lived at the time), is about the same; it’s suitably distant from civilization, and was said to be beautiful, peaceful—and wild.

I already knew I wanted us to go with Downeast Whitewater, the company that had taken us on both runs through the Kennebec. I’ve noticed the same tendency among other whitewater dilettantes: once you find a company you like, you tend to stick with it. It’s not that the other companies are inferior, and it’s not just familiarity, either. It’s more that rafting companies are like families, and the companies that run the same rivers are like far-flung branches of extended families. All the guides within a single company know each other well, and know the guides of other companies the way you probably know your cousins. I’ve never known a river guide who wasn’t fiercely loyal to the company for which he or she ran, and most can be induced, after an off-duty beer or two, to share gossip about the other companies.

River Runners

River runners are a special breed. Actually, they have something in common with me: we have both discovered careers we love. I have to make a special effort to not eat, breathe and sleep computer programming. For me, rafting is a way to escape the bonds of that love, to remind myself that, fun as it is, there is more to life. The guides are the same about river running. It’s such a part of their lives, they use river-running jargon to describe non-river-related events. One guide I know once referred to his relationship with a former girlfriend as "hydraulic". It was a while before I learned that a hydraulic is a place in a rapid where the water rushes in an up-and-down, circular motion. A swimmer caught in a hydraulic will pop to the surface, then be dragged back to the bottom, over and over. It’s a wild ride in which the swimmer will be given many false hopes; but in the end, without rescue, the swimmer drowns. I’ve known of relationships like that, but never had a good word to describe them, until now.

"Hydraulic" also applies to the life of a river runner, because the job, by nature, is seasonal. Many of the Maine guides become ski instructors for the winter. Some manage to turn their passion into a year-round job by running Costa Rican or African rivers during our winter months, but because there are many more U.S. rivers being run than anywhere else, this is not an option they can all choose. And, of course, the travel would be at their own expense. River guides do not make a lot of money. But the truth of the matter is, they don’t much care. They’d run the rivers for free if there was no other way.

The scary part is, I understand this. Yes, I love my job. But if I didn’t…or if I get tired of it…I could see myself becoming a river runner, too.

Or, maybe I should become an adventure travel agent. I got plane tickets for everyone, relying on frequent flyer miles and unused ticket refunds to bring the cost into this universe. My planning all had to fit into the few days I was home between teaching assignments, but I was very proud of the planning and I worked hard to do as much in advance as possible, hoping to keep things running as smoothly as possible. I made the reservations with Downeast; even reserved campsites at Pray’s Big Eddy Campground. That last had to be done by mail, since Pray’s is thirty miles from the nearest telephone. I found that to be its biggest selling point, in addition to the fact that Downeast would meet there at 7:00 am on the day of the rafting trip, and that’s awful early for me to have to find my way there from somewhere else—my brain doesn’t switch on until sometime between 9:00 and 10:00 am.

The Kids Arrive

The well-laid plans began going awry with the non-arrival of Jennifer’s flight from Florida, which had been canceled. Jennifer is a rather self-sufficient person to whom it never occurred I might like a phone call if her flight should be delayed or worse. However, I was able to determine from the airline desk when she would actually arrive—about three hours late, on another carrier. Dottie and Critter, arriving on another flight, were also delayed a couple of hours. And John and Rachel, scheduled to fly in at 11:25 PM, didn’t actually make it until about a quarter to one. While waiting for them, I was told by the airport security guard that their particular flight never arrived on time—hadn’t in the year and half he’d worked there, anyway. Sometimes it came in as late as 3:00 am, so I had to consider myself lucky.

Still, the first hurdle had been passed: everyone had actually arrived. I drove them to my townhouse where we were spending the night before leaving for Maine. Dottie and John hadn’t seen Jenny in about two years, so it was quite a reunion.

The next morning saw us up at the entirely reasonable hour of 9:00 am, packing the rented van. The kids had been given checklists: quick-drying shorts or bathing suit, river sandals, sleeping bag, tent, towel. At least we had enough tents. But three people (my daughters) didn’t have sleeping bags; four didn’t have river sandals; and only one person brought a towel. I had planned to buy groceries on the way, so I grit my teeth and figured on stopping at a K-Mart as well.

By 11:00 am, we were actually on our way. The van was packed full, yet we still hadn’t shopped. We wound up stopping at four different stores before we got to Bangor; by then the van was so full of clothes, food and new camping gear that I hadn’t expected to buy but suddenly realized we couldn’t live without, that the kids had to put their feet on each other’s laps.

I had considered flying everyone directly into Bangor to save four of the six hours’ drive; but the fares there were considerably higher than they were to Manchester which, while small, is still a major airport. . Bangor was our last sign of urban civilization. An hour later we left I-95, passed through East Millinocket and then the "real" Millinocket, which is a nice little town but no city; and then headed toward Mt. Katahdin, exactly one mile high and the highest in Maine. The area isn’t very mountainous, so Katahdin (pronounced Kah TAH din) rises like a Sphinx over the flat green forest. In addition to being tall, it covers a lot of ground; so when you look at it, you see layer beyond layer of tree-covered hill, each slightly bluer with haze than the one nearer.

Pray's Big Eddy Campground

We came to a gatehouse, marking the entrance to land owned by a lumber/paper company—Northern, the toilet paper people. We had to sign in and pay $4.00 entrance fee. We also had to tell exactly where we were going and why, and were given a registration for the campground to stamp to prove, I suppose, that we had actually gone where we said we intended to. For some reason lumber people seem to be really nervous these days.

"Pray’s Big Eddy Campground" seems like an awkward name until you break it down. The people who own it (lease it, actually, from the paper company) are named Pray. The campground is on the bank of the Penobscot, at a point where the current forms an eddy (a place where the water moves around but doesn’t actually flow anyplace). If you were to plant yourself in an inner tube, say, and push off from the bank, you’d slowly rotate out a ways, then back in, until you had returned to your starting point. Some eddies are small, but this one is large enough to have earned its own name: Big Eddy.

Have I mentioned that Maine is known for its insects? Especially biting black flies big enough to saddle? We all had to drench ourselves in insect repellant.

We had been assigned two adjacent campsites right on the river bank. One was smaller than the other; I took that for my own and also made the fireplace and neighboring picnic table our communal kitchen.

The kids pitched their tents on the other site, about twenty feet away from mine. Pray’s is a pleasant place, primitive, where there’s no phone and they make their own electricity as needed…which means, not all night long. Still, there were lights, hot water and showers until at least 11 PM when I turned in. However, I had forgotten that campgrounds such as this often charge for showers, using quarter-fed timers; and I had neglected to bring quarters. We had a few in our loose change. Fortunately, not everyone wanted a shower that night, and we knew we could get change from the office in the morning. Besides, we’d probably get wet enough in the river!

We had an early morning wakeup planned, but the kids, being young adults, saw no reason why that meant they couldn't stay up all hours partying. Even Jenny, who wasn't seeing anyone at the time, was able to find a random camper to hang out with us.

I had scheduled morning wakeup at 5:00 am, but it was nearly six before I stopped hitting the snooze button on my travel alarm. I roused the kids and started breakfast: Pork and turkey Sizzlean (like bacon, but less fat), scrambled eggs, orange juice and coffee cake. I found it interesting that, given a choice between fresh-squeezed orange juice and orange soda, most of the kids went for the soda. I couldn’t really say anything, though, since I myself had eschewed coffee in favor of Diet Coke.

It was not promising to be a hot day, and it wasn’t sunny. Several of the kids complained about being cold during the night, although I had slept great. I love sleeping outside (or in a tent). Something about the fresh air and the sounds of the night insects and early morning birds makes for a restful sleep. I had offered to rent wet suits for anyone who wanted one; only John and Critter decided to go without.

Jenny and Karen are so slim the smallest wet suits Downeast had were still loose on them. Downeast requires rafters to wear helmets; Karen wasn’t happy about that—she didn't want it to mess up her hair. Besides, the color of the helmet, she said, clashed with that of her wet suit. And, of course, the paddles we were assigned didn’t match at all. But, I thought, she still looked cute.

Safety Lecture

A guy named Larry gave the safety lecture. I had heard it before: what to do if you fall out of the raft, why we have to wear lifejackets, etc. It was difficult for me to concentrate, however, since Larry was a dead ringer for Charles Manson. Larry was also memorable for a demonstration—we were warned "not to try this at home"—in which he inserted the entire T-grip of a paddle into his mouth. That was something you don’t see everyday. Larry finished by thanking us for supporting the prisoner’s weekend release program.

Guides were then assigned to the various groups. We got A.J., a good-looking 22-year-old with eyes and dimples that reminded me of a young Kurt Russell . Since there were seven of us (in addition to A.J.), we made an entire crew and got our own raft.

Different companies do things differently, but Downeast rafts the lower part of the Penobscot first. That’s because the more difficult rapids are in the upper Penobscot. By running the lower river first, the crews have a chance to learn the skills necessary to run the upper river.

A.J. explained to us the commands he’d be issuing. "All ahead" and "All back" were self-explanatory. "Left back" meant that the paddlers on the left would paddle in reverse while those on the right would paddle forward; "Right back" was the inverse. "Take a break" meant we could quit paddling for a bit. The most interesting—and intimidating—instruction, however, was the "Oh, shit!" command which, A.J. explained, meant we were to hold the T-grips of our paddles with one hand while grabbing hold of a rope inside the raft with the other and holding on for dear life.

Our First Rapid

The first rapid we ran was called Nesowadnehunk Falls—class IV on a scale of I to V. (Rapids beyond V are considered unrunnable.) The first-timers among us, at least the girls, admitted to being a little nervous; but no one wanted to back out now. Jennifer was a first-timer but she’s always been fearless; so she volunteered to be one of the lead paddlers. That put her in the front of the raft, responsible for setting the pace of the paddlers behind her. Critter took the other front position. A.J. explained just how he planned for us to run the thing, including alternative plans in case his first plan didn’t work out. Of course, we didn’t really understand anything that he said, but it did give us the feeling that he knew what he was doing.

The thing was impressive, I’ll give it that. The roar was intense enough to feel. We could see the top edge of the fall, and the river nine feet below and beyond it. A.J., in the back, steered and shouted commands: All ahead! Left back! Right back! We fumbled some, but managed to make the raft do what he wanted it to do. The raft spent a brief moment poised on the edge of the fall, then began to drop into the frothing spray. A.J. yelled, "Oh, shit!" and we obediently made sure our paddles’ T-grips were in one hand while we held on to the raft with the other. It dropped the nine feet, barely missing the enormous hydraulic waiting beneath to swallow us, pulled out to the right and then went spinning past the chops into the calmer water beyond.

"I’m glad you all remembered the ’Oh, shit!’ command, A.J. said afterward.

Rachel looked embarrassed. "I didn’t," she confessed. "I thought you meant we were all going to die, so I just hung on tight."

A.J. nodded. "That’s why it’s called the ‘Oh, shit!’ command. It works whether you remember it or not."

The rest of the morning was filled with more rapids, including Pockwockamus Falls, a 900-foot roller coaster of standing waves, each scarier than the one before it. But there were more peaceful moments, too: drifting through a quiet spot, we encountered a mother moose and her baby. Mama glanced at us, obviously thought, "Oh, it’s just those weird floating humans," and led her baby across the river to the other bank.

And then there was a natural slide, where we could jump into the water and have it propel us down this smooth granite face, like Mother Nature’s Slip ‘n’ Slide.

The Cribworks

Finally we "took out" and boarded a bus that took us to a beautiful spot overlooking the wildest rapids we had yet seen. Downeast cooked and served steaks, "river rice" (stir-fried rice, red cabbage and onions seasoned with ginger) and cole slaw, washed down with lemonade and/or coffee. A.J. came by and asked us what we thought of it.

"It’s pretty wild," Dottie admitted.

"That’s the Cribworks," A.J. said. "It’s class V. We’ll be running it this afternoon."

Dottie just looked at her steak as if it might be her last meal.

The bus took us to our afternoon put-in at the base of a dam. (Many rafting trips start at the bases of dams.) The water rushing from the dam was contained by Ripogenous Gorge, making for instant rapids; but by now we were ready for them…or thought we were.

However, in running the Exterminator, Karen didn’t hang on to the T-grip of her paddle and it caught John on the knee. That took John out of the raft and limping back to the spot overlooking the Cribworks. He didn’t seem to mind too much, though; without a wetsuit, he was shivering a little anyway. He took the camera with him to take pictures of us running the Cribworks.

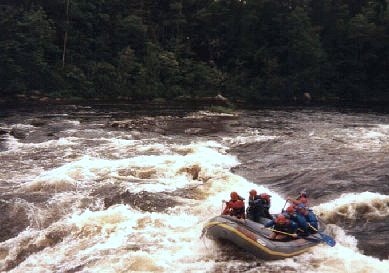

It was our turn to go, but a raft from another company butted in front of us. It served them right; they got hung up between a couple of rocks and it took over a half-hour for them to get free. No one was hurt, but of course John was panicky; he thought it was us, and, at that distance, couldn’t be sure one way or another.

A.J. decided to run the Cribworks in a conservative fashion, because we weren’t the strongest group he’d ever had—and now, John, one of our strongest members, was not in the raft. So we took an easier route through the water. It surrounded us; there were standing waves everywhere and there were rocks to avoid. It all depended on our obeying A.J.’s orders promptly—and that depended on our hearing them over the roar of 30,000 cubic feet of water rushing per second through a channel too narrow for the job.

But by now we were a team. If the two people in front could hear A.J. from the rear, everyone would follow their lead. And the people behind were quick to pass commands up to the front if it appeared they had not been heard.

All the planning was done in the quiet of an eddy, but now it was time. We pushed out into the current, felt it take us. "Back left!" Those on the right paddled forward, those on the left, back. We rotated counter-clockwise until we presented the angle to the Cribworks A.J. wanted us to have. "All ahead!!" Then, "All back!" That gave us the extra second we needed to drift a few feet further to the right. "Oh, shit!" We grabbed at the ropes in the raft, wedged our feet under the rubber gunwales. We had just seen a raft overturn here, and another one—that could have been us—lodge between two rocks. Usually it doesn’t matter if you fall out because we’re all wearing lifejackets and helmets. But a dunking here, while probably not fatal, would not be much fun—and you’d have to float through the whole thing, standing waves, hydraulics, and all, before you could be rescued.

This picture was taken by John of our raft running the Cribworks. On the port (left) side of the raft, from front to back, is me, Karen and Dottie. On the starboard side, Critter leads, followed by Rachel and Jenny. A.J. is in back steering for dear life. We are, at this point, moving backwards.

But we didn’t overturn, and we didn’t lose anyone. Next thing we knew, A.J. was directing us to continue paddling. We dodged a couple of enormous hydraulics, and then deliberately entered one. He got us to move forward in the raft; the rear end lifted into the air and we balanced on the edge of the tumbling water for a full minute before he had us return to our seats. The hydraulic spit us out and we continued down the river, into quieter waters and our take-out.

Everyone had a wonderful time—even John, whose knee healed pretty fast. Although we had reservations to stay another night at the campground, we would have had to awaken about 3 AM to get back to Manchester in time for everyone’s flight out; so we decided to go ahead and book. We did invite A.J. to share dinner with us in Millinocket, which he did.

Now that the kids are older and have jobs, it's such a major logistical nightmare to get them all together at once—even for something like Christmas—that it's not very likely we'll be able to have another family rafting trip. But, that's okay: We had this one, and none of us is likely to ever forget it.