| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 5/4/2024 Posted: 4/23/2024 |

Page Views: 349 | |

| Topics: #Photography | |||

| The very unintuitive way to extract a decent photo from a newspaper clipping. | |||

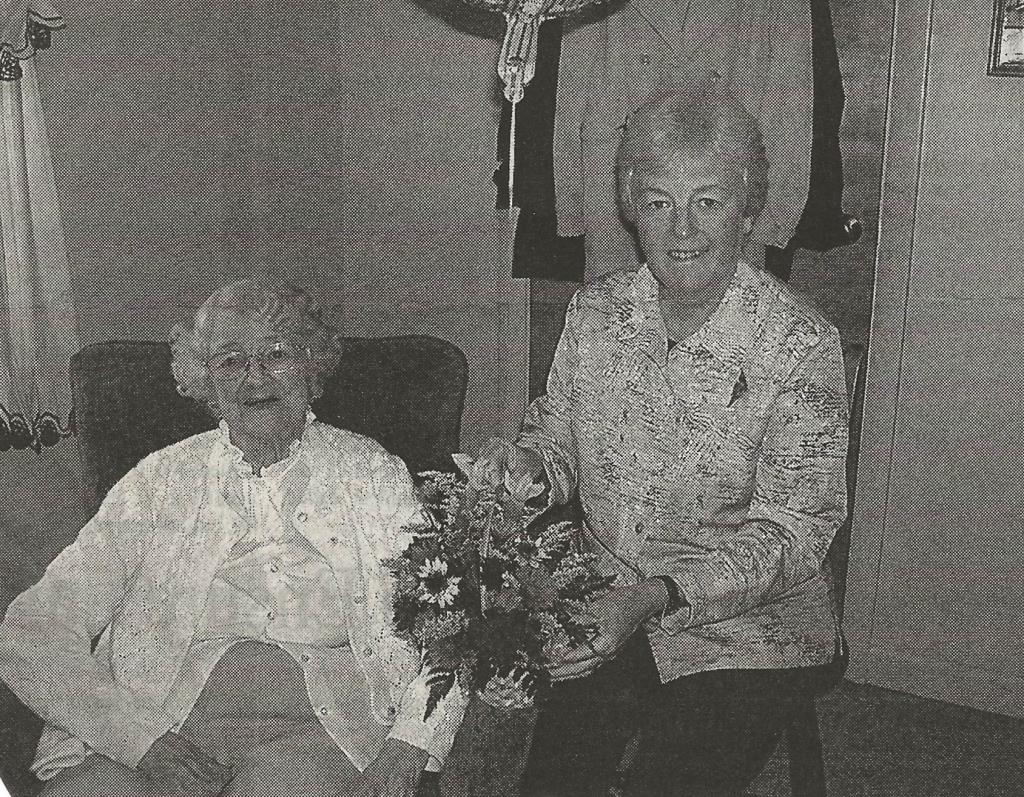

First, let me explain why I even care. My second grade teacher was Mrs. Alice McGinnis of Lyndonville, Vermont. I loved her. And when I grew up and returned to Vermont to visit, I visited her. On several different occasions. And we corresponded. So when a friend sent a newspaper clipping on the occasion of her 97th birthday in 2006, I kept it. (She has since passed on.) But, as you can see from the scan of the clipping, you can hardly make the poor woman out. So I decided to do my magic and get a decent restoration out of it. As a challenge.

All printing, even computer printing, uses something called halftone printing to render photographs. Halftone printing is a reprographic technique that simulates continuous-tone imagery through the use of dots, varying either in size or in spacing, to create a gradient-like effect. This method allows for the reproduction of photographs and intricate images using only one color of ink, with the dots' size or spacing modulating the intensity of the tone.

The human eye, when viewing these dots from a sufficient distance, perceives them as smooth tones, creating the illusion of a continuous-tone image. The halftone process was a significant advancement in printing technology, enabling the realistic reproduction of photographs in mass commercial printing, which previously relied on hand-carved blocks of wood or metal engravings that could not capture the subtle details of a photograph. The first successful halftone image was printed in 1880 by Frederick Ives, an American inventor.

Extracting a reasonable copy of the original photo from a halftone print presents challenges due to the nature of the printing process. Halftone printing translates the continuous tones of an image into a pattern of dots, which can be difficult to reverse without losing detail. Continuous tone copy, which includes photographs and other images with unbroken variations in tone, is more challenging and expensive to reproduce on a printing press. This is because printing plates are designed to print solid areas of color and cannot replicate the different shades of grey that make up a photograph. As a result, the halftone process is used as a workaround, but it inherently introduces limitations when trying to recreate the original continuous-tone image. The dots in a halftone image partially overlap and vary in size, making it complex to extract a clean, continuous-tone copy from the printed halftone without sophisticated image processing techniques.

Nowadays with AI-powered photo editing software, a halftone photo is considered noisy

and so noise reduction filters usually do the job. However, that would be with finer

printings, such as a magazine illustration. Newsprint is really cheap paper

and so the halftone dots have to be bigger. A halftone photo like this one

of Mrs. McGinnis is so extreme that you either have to dial the noise reduction back so far it does no

good, or forward to the point the picture is unsuitable, like this:

However, there's a very unintuitive way to get around this. You shrink the picture down to where the shrinking process blends the little dots together, making genuine tones of them. This is counter-intuitive because you feel like shrinking the photo loses information. But in the case of shrinking a halftone image, it doesn't really; because there isn't really that much information there.

.jpg)

Now that the photo has been shrunk, I can give it to Topaz Photo AI to do its thing. That's the same program that produced the first result. But check this out!

When I saw that result, my jaw dropped. I'd hoped it would help, but it actually gave me something I could work with! I did a little contrast leveling and spotting with Zoner Photo Pro (not an AI app but very capable) to get it ready for the final step.

That last step, currently, I must do on my phone, where the Colorize AI app runs. Once in awhile, that gives me a final result I'm happy with. More often, I use it as a good starting point but then basically paint over what doesn't work.

This can be anything from tweaking just a few colors, for example, with school uniforms the AI hasn't been trained on, to practically having to repaint the whole thing. Luckily that's rare. Here's my final product:

So now I have a finished product, ready to incorporate into a post here about my dear, departed teacher.