| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 7/26/2024 Occurred: 7/26/2006 |

Page Views: 6884 | |

| Topics: #Music #PaulSimon | |||

| Review: Paul Simon's concert. | |||

Our friends, Barbara and Peter, offered to take Michael and me to a one-night-only Paul Simon concert as our upcoming anniversary present. The concert was last night. The four of us drove across the Valley to Sun City West, where the concert was being held.

Sun City, as you may know, is a retirement community (and the place where my novel, The Sun City Cannabis Club, written with Jock McNeill, takes place—plug, plug!) Anyway, Sun City was such a successful real estate ploy that its developers decided to construct an annex—but, by that time, the town of Surprise had developed in the only direction Sun City could grow (which no doubt surprised the hell out of the developers, hence the name) so, heading west, you have to drive through Surprise to get to Sun City West. But there's still lots of retirees. And it got me to thinking…how old is Paul Simon, anyway?

His and Art Garfunkel's hitThe Sound of Silence came outwhen I was in high school. Simon was born October 13, 1941, making him almost tenyears older than me. That means he's almost 65 years old—qualified to live in the Sun City retirement complex.

How did this happen? I've known quite a few old people through the years. They eat mild foods to avoid upsetting their ulcers; have screen doors on their homes so they can leave the solid doors open; they know the names of the parents of the Lennon Sisters and have opinions about the young men they married. They do not listen to, or understand, rock 'n' roll. So how can an official old person be Paul Simon, the writer of The Boxer, The Sounds of Silence, Mrs. Robinson, Bridge Over Troubled Water?

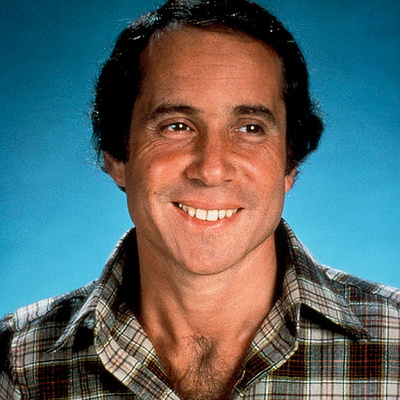

Paul Simon was really cute when he was young. I always thought that, of Simon and Garfunkel, Simon was definitely the sexiest. Garfunkel always had that hair thing going. Actually, Garfunkel's hair looked a lot like mine, and I hated my hair; so that may have had something to do with my assessment. But Simon's hair was straight and tousled and he usually wore jeans and a ball cap which I thought made him look really butch.

I remember where I was when the local radio station played Bridge Over Troubled Water for the first time. It was Tampa, Florida, where I was attending an electronics school. A station employee had flown into Tampa specifically to hand-deliver the freshly-pressed disk. I was driving on a cold winter day and I remember thinking, as the powerful piano chords began, that not many pop artists would have the nerve to write a song that wasn't rock 'n' roll. When they broke up shortly after, I wondered who would dare to innovate now that Simon and Garfunkel were no more?

A couple of years later, I myself was working in a radio station and often played Duncan, a newly-released single from Simon's first solo album. It never went very high on the charts (reaching number 52), but I liked it—a raw narrative of a young man's seduction by a female preacher not unlike The Boxer. It seemed that Simon had smoothly made the passage to solo performer. In the following years he would reinvent himself repeatedly.

And now, as we sat waiting for the opening act to end and for Simon to appear, it occurred to me that much of Simon's music—especially the stuff he's done since he and Garfunkel split—is almost intensely heterosexual. That is, it graphically and grittily describes the heterosexual experience. I'm not saying that only straights can enjoy his music; I'm saying there is an element in many of his songs that almost defines what it's like to be a heterosexual man in late 20th-century America, much as the internalized broken hearted themes of the modern musical theatre define the heart and soul of homosexuality. Compare a typical love song that gay men all know the lyrics to and would sing out loud at a piano bar:

There were bells on the hill

But I never heard them ringing,

No, I never heard them at all,

Till there was you.

Now, contrast that to these lines from The Boxer:

Asking only workman's wages,

I come looking for a job,

But I get no offers,

Just a come-on from the whores on 7th avenue

I do declare, there were times when I was

So lonesome I took some comfort there…

See the difference? The gay experience is all sparkly and magic and unreal. In Simon's gritty hetero narratives, you can only hope the protagonist has gotten his shots.

Listen to I Am A Rock:

I am a rock, I am an island.

And a rock feels no pain,

And an island never cries.

By his singing the story of the emotionally-stifled protagonist, Simon reveals that he recognizes the tragic plight of the man's man of the mid-twentieth century. Because such a man does feel pain; of course he does—but he denies it even to himself. And in film after film, John Wayne and Gary Cooper and their clones demonstrate to us all that that is the way to be. Every straight man knows that, right or wrong, this impossible state of imperviousness to pain or tears is what is expected of him. Every gay man imagines that straight guys can actually do this; and we know that our inability to live up to (or down to) this requirement is the main reason we could never be straight.

It's the conflict between this perverse masculine ideal and the reality that makes the situation inBrokeback Mountain so poignant. "If you can't fix it, you jes' got to stand it," says Ennis to Jack of their doomed love. He's quoting the unspoken Man Rule that Simon understood so well. A straight man who loved an unattainable woman would just become an alcoholic, as Ennis does, or shoot everyone who stood in his way. A out gay guy in love with an unattainable man will cry, moan, whine, agonize, and annoy all his friends until they become alcoholics, or bitch slap anyone who stands in their friend's way.

Anyway, the audience at the concert was curiously composed. There were the old folks I had imagined would show up, being that the concert was held in a retirement community; but they only made up about half the audience. The other half seemed to be the grandchildren of the first half. I saw very few fortysomethings in the audience, but lots of fifty- and sixtysomethings, and many, many twentysomethings and even teenagers.

Paul Simon's first major reinvention came with his Still Crazy After All These Years album. (Another hetero song—straight men brag about retaining their wild and crazy youthful impulses just as they reach the age when gay men have almost finished alphabetizing their extensive and complete collection of vintage Bruckner albums, or green Chinese pottery, or whatever that particular gay man has decided to devote his life to collecting.) His second came with his Graceland album, a huge hit which introduced World Music to the somewhat limited ears of straight Americans. So, I thought, I guess this performer is truly an artist whose appeal is to the ages. The teenagers would be hoping he'd sing The Boy In The Bubble while their grandparents would be looking forward to Kodachrome or The Boxer.

Or, perhaps, his core fans had been forbidden by their doctors to drive after dark, and they had to get their grandchildren to taken them. Certainly that was the case with the three Big Hair Women who sat directly in front of Michael, Barbara and me; their giggling granddaughters sat just down from them. It was annoying, too, because most of the audience had gone for the more expensive tickets, leaving a huge, empty, cheap seat swath in front of them.

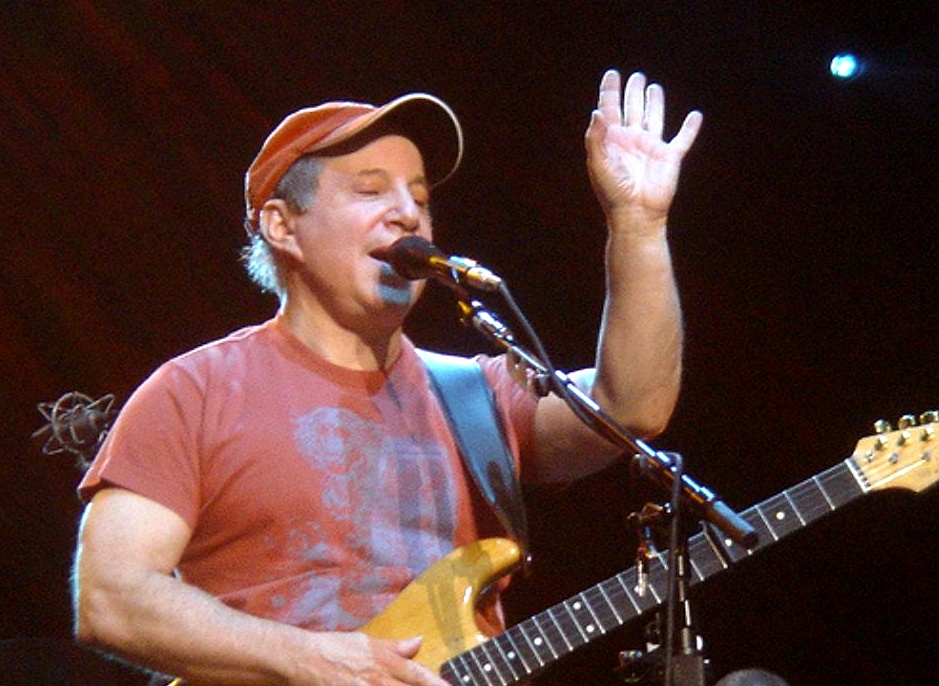

After an excellent performance by the opening act, Jerry Douglas, Paul Simon finally came on stage. The audience went wild, but I was dismayed. This was not the cute kid I remembered from my high school days. He was a cute old guy. In fact, as I saw his face enlarged on the twin television screens that flanked the stage, I could swear I had seen him personally—and recently. He looked for all the world like the guy who had been in front of me in line at the drug store a couple of days ago. The pharmacist had made a big deal over my needing to stand on the other side of the line of black tape that had been applied to the floor and labeled Privacy Line. "That's so you can't hear me give directions to other people," the pharmacist explained. "And they won't be able to hear what kind of medicine I give you, when it's your turn."

I promised to stay behind the line, even though my medicine isn't anything embarrassing—just a little something to control my high blood pressure, which I probably wouldn't have if the world wasn't rapidly filling up with taped lines telling us where to stand. But then this guy ahead of me turned out to be hard of hearing, so the pharmacist had to yell the instructions for his incontinence medicine so loudly that it could be heard all over the store.

Anyway, that guy looked an awful lot like Paul Simon looks now.

And that baseball cap? Puh-lease. Baseball caps are hot when you are not too old to play baseball. After that, they are simply code for, "I'm bald."

But I forgot all that when as Simon started singing. He did a three-number medley from, I assume, his upcoming album; yes, he sang The Boxer and Graceland and Slip Slidin' Away and Diamonds On The Soles Of Her Shoes. And he left and was brought back by the audience for three encores, one of which included a rock version of Bridge Over Troubled Water obviously done to be as different from the original, sung by Art Garfunkel, as possible.

And his voice isn't quite what it once was. I understand Simon quit smoking years ago when he saw what it was doing to his voice; and he still seems to have the range and purity of tone he always had. There's just not quite the same amount of control. But, heck, he's almost 65. I don't have that amount of vocal control now.

Except for the members of the audience who left after the first encore, hurrying, I assume, to get home so they could take their medication on time, when Simon finally left the stage for good the rest of us left the venue slowly—a good sign, I think, that shows we all really enjoyed ourselves.

As for me, I am pulling out all my Paul Simon and Simon and Garfunkel albums to give them a fresh listening to. Whether he writes about the "heterosexual experience" or not, Simon's music is also universal; and no matter how old he gets, I suspect I'll continue to enjoy it as long as I keep breathing.