| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 7/26/2024 Posted: 4/5/2006 |

Page Views: 5097 | |

| Topics: #AlienAbductions #GrandCanyon #WhitewaterRafting | |||

| The layers of people's personalities peel back just as Grand Canyon reveals its layers of geology. | |||

On the expedition's eighth day, we arrived at Phantom Ranch and said goodbye to the passengers who could only be with us for the first eight days.

The trip from Lee's Ferry to Pierce Ferry at Lake Meade is 280 river miles, and the rafts have to make the whole trip. However, the passengers don't; and many people can't spare the time for a eighteen-day trip—or the money. So O.A.R.S. divides the journey into three segments. The first is the "Upper Canyon" and runs from Lee's Ferry to Phantom Ranch, about eight days downriver. The second is the "Lower Canyon" and picks up where the "Upper Canyon" left off at Phantom Ranch, going another seven days to Whitmore Wash. The remaining three days is called the "Canyon Sampler" and runs the rest of the way to Lake Meade. The Canyon Sampler is the trip I had made with my daughter in 1992.

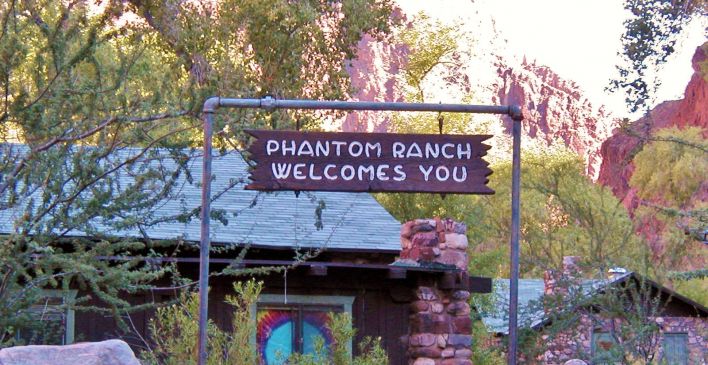

Phantom Ranch lies near the bottom of the Canyon on the Bright Angel Trail. Mules and humans travel that trail; no mechanized vehicles can traverse it. Phantom Ranch itself is a quaint, century-old lodge with a communal dining hall and dorm-like facilities. As the closest we'd come to civilization in a week, none of us passengers chose to remain with the boats rather than have a "civilized" lunch in the dining hall. We could also send letters and postcards that would be marked "MAILED BY MULE".

The fifteen passengers who were leaving would actually spend the night in the dorms, and begin their nine-mile hike up Bright Angel Trail before dawn. Meanwhile, as we all ate lunch, replacement passengers were hiking downward to the river. We expected them to arrive by noon.

Liz and Kathleen hugged me goodbye and I shook hands with a few of the departing guys. Even the gay doctors politely said farewell. Judy, on the other hand, ignored me as studiously as I ignored her. Anne had accompanied us to the Ranch to check her and Tony's mail; I noticed she walked stiffly, as if she were in pain. She couldn't bring herself to look Judy in the eye, either.

Wearing my new Phantom Ranch T-shirt, I returned to the rafts to find a few new passengers had already arrived. There was Larry, a stand-up comic from Los Angeles, and Matt, a fireman from San Francisco. There was, however, no sign of Rusty's generals.

"They'll be here soon," Rusty assured me. "They were all roommates at West Point."

"How do you know that?" I asked. "I don't remember a place on the reservation form for 'biography'."

"It's in the trip notes," Rusty explained. "O.A.R.S. must have talked on the phone with whichever one of them made the reservation."

I couldn't say he was wrong. My reservation had been made by my travel agent, so there'd been no reason for me to talk with O.A.R.S. at all.

By one o'clock all the new passengers but the generals had arrived. New passenger Larry knew exactly why they were late. "They said they had marched in Korea and they had marched in Vietnam and a silly little nine-mile downhill hike was no reason to get up so early," he reported. They had slept in while the other passengers began the trek. And now the others were here at the river, but the generals were not. So we waited.

About an hour later, a lone hiker, not one of the passengers, appeared on the bluff above us. "Hey, are you missing three old guys?" he called down.

"Yeah!" Robby answered. "Have you seen ‘em?"

"Sure have. They're about four miles back on the trail. One of ‘em is in bad shape." So Robby sent Tony and Rusty, our burliest boatmen, running up the trail. After another hour or so they reappeared with one of the West Pointers limping between them. Yes, these guys may have once been power walkers but now, after twenty years of holding down the desk they were not in such good shape. Butch, the guy whose legs gave out on him, was only 63 but he looked like he was gonna collapse any minute, and the other two weren't much better. I wanted to start a betting pool on which day of the trip Butch would die, but Robby talked me out of it.

In fact, he tried to talk Butch out of staying at all. Tony and Rusty had carried him to the river only because a helicopter couldn't land on the slope of the trail; and taking him down to be picked up made more sense than dragging him up to the rim. But both boatmen had assumed he would be flown out. Crippled, Butch would have no way to get to the latrine, much less in and out of a rubber raft.

But Butch's personal doctor was one of the other generals; and he vouched for Butch's rapid recovery. In the meantime, both of his companions would be glad to carry him to the latrine, and in and out of the rafts, as needed. So Robby relented and Butch stayed.

"Where's Schwarzkopf?" I asked Rusty.

"He couldn't make it," Rusty said, with a hint of disappointment. "I guess there's a war or something. But now's your chance. Go talk to those guys about UFOs." I just glared at him in return and made myself available to any of the new passengers who needed assistance closing their dry bags or fitting into their life jackets.

Another new passenger had special concerns. Her name was Virginia, and she was blind. I showed her by feel how to work her dry bag; she caught on more quickly than many of the sighted passengers. "I hope they don't make special allowances for me," she said. "I've done a lot of adventure traveling and I really don't need any." I decided to take her at her word.

When we were all packed, I rode with Larry, Matt, and a woman named Carol in Mike's boat. We went just a few miles downriver before stopping to hike. The new passengers, already overwhelmed by the beauty of the canyon, lined up eagerly to start out. Soon we were following Tony (and trailed by Brian), climbing several hundred feet above the river on a trail that followed the softly rounded edge of an overhang. Each of us tended to walk at a different pace; soon Tony was out of sight ahead of us and Brian was somewhere behind.

Suddenly, Larry slipped on loose gravel and fell, sliding down toward the edge of the overhang and a fatal drop. I had been right behind him, and threw myself to the ground so I could grab the strap of his day pack. That halted his slide, and Matt held my ankles firmly so I could pull Larry back to safety without slipping off myself.

Larry was furious. "This is dangerous!" he cried. "Why isn't there a guard rail? Why doesn't someone clean loose gravel from the trail?"

I burst out laughing. "This is a wilderness, Larry!" I said. "If you wanted a safe stroll, you should have taken your vacation in Disneyland."

Tony came jogging back. "Is there a problem?" he called, then, seeing the scrapes on Larry's knees, added, "Are you all right?"

"Yeah," Larry growled, "no thanks to the Park Service, who should have put in guard rails here."

"Guard rails?!" Tony snorted. "Oh, you're one of those guys who thinks there should be mile markers posted along the river, too, aren't you?"

"It would make the map easier to follow," Larry pointed out, aware that Tony was gently ridiculing him.

"Look, man," Matt interjected, "I'm a fireman. And I've got to tell you, you will never be completely safe, anywhere you go. No matter what you do. There can always be an earthquake."

"Or a meteor could hit you," Carol pointed out. When everyone stared at her, she said, "Well, I'm from Kansas, and at home a meteor is about as likely as an earthquake—and less likely than a tornado."

"Or you could be having a harmless little fling with a White House intern and be exposed by a busybody reporter," Tony added. "The point is, 'safety' is an illusion. One of the gifts of Grand Canyon is helping you come face-to-face with that illusion, so you can see it for the lie it is. Once you do, you'll be a better person for it."

"If I live," Larry grumbled, but I could see he was beginning to understand.

"Follow me," Virginia, the blind woman, suggested. "If anyone is going to slide it will be me; and that can serve as a warning that the path is slippery." We stared, not certain whether or not she was kidding.

When we resumed rafting, I decided to take Larry, Matt and Carol into my confidence. "Look," I said. "In that baggage boat. That's Rusty."

"What about him?" Larry asked.

"Well, there's this thing. See, he's going to tell you anyway. I'm an alien abductee."

Larry laughed out loud. I took it good-naturedly.

"Yeah, yeah," I said. "The point is, that's all Rusty wants to talk about. Every single night. So, I was thinking that, if you guys hang out with me tonight while we eat, when he tries to bring up aliens, you guys could, like, change the subject."

My three new friends agreed to help, and Mike the boatman added, "Give me a high sign if he gets stubborn. I'll take the pressure off you."

"How will you do that?" I asked.

"Oh, I have a trick or two up my sleeve."

When Phil handed out the tents that evening, the generals politely declined. "We have our own tent," one of them explained.

"That big old thing?" Cathy, the other baggage boatman, asked. "That heavy canvas thing I've been rowing around all day?"

"Are you sure you wouldn't like a modern backpacker's tent? We have a spare or two."

"We're sure," said Butch, who still couldn't walk. "We used that tent in Korea, and we used it in Vietnam. It's certainly good enough for Grand Canyon!"

As I predicted, Rusty joined Larry, Matt, Carol and me for dinner. He introduced himself and sat down on the beach with his plate of tortellini Alfredo. He hadn't taken three bites before announcing, "Paul's an alien abductee."

"Oh, puh-lease," Matt begged. "I'm from San Francisco. Alien abductees are a dime a dozen. Straight guys like me are rare."

Rusty refused to be deterred. "Have you ever seen a UFO related to one of your abductions, Paul?" he asked.

"I have a stand-up routine about UFOs," Larry remarked. "What's the difference between an intelligent man and a UFO?" We looked at him blankly, and he gave us the punch line. "I don't know. I've never seen either one!" We laughed, but he wasn't done. "Hey, where do dumb aliens go? Area 52! Y'know why cats hate flying saucers? It's too hard to reach the milk."

"Do you know how men are like UFOs?" Carol asked suddenly.

"How?" Larry responded.

She sighed. "You don't know where they come from, or what they intend to do. All you know is, just when you've gotten used to them being around, they take off!"

Larry laughed. "That's good! You can tell a joke!"

"I date Kansas men," Carol said primly. "Being able to tell a joke is the only way a Kansas woman can survive."

"But, seriously, Paul," Rusty insisted. "Have you ever had an anal probe?"

Matt snorted, "Most of my friends have. Some of them will even pay extra!"

It was clear that Rusty wasn't going to give up, so I caught Mike's attention across the campfire. He stood and banged on a saucepan. "Okay, folks, time for tonight's entertainment!" Everyone quieted down and give him their attention. "Some of you know I come from Alaska," he said. "Now, I don't know many Grand Canyon stories, but I do know an Alaskan story about the Cremation of Dan McGee." He put down the saucepan and began to recite—no, to perform—the Robert W. Service poem:

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee…

Everyone was spellbound. The story of the hapless Tennessean who found himself freezing in the long Alaska night only made the coolness of this night seem to penetrate to our bones. I gazed past the rapt faces of Matt and Carol and Larry to Rusty, who was frowning at me. I gave him a smirk and a wink, and returned my attention to my new best friend, the boatman from Alaska.

Rusty rose during the recitation; I saw him a little later with the generals as they put up their tent.

Mike finished and an enthusiastic round of applause reverberated between the canyon walls. When the echoes had died away, Mike said quietly, "Y'know, I really have seen a UFO."

"So have I!" Carol whispered in surprise. "I've never told another soul. What did yours look like?"

"Just a translucent disk or sphere," Mike said. "I was hiking in Yosemite and it flew overhead very fast, but at an irregular pace."

"Mine was more solid than that," Carol confessed. "I was just a little girl, maybe eight years old, when I saw this—thing—zoom overhead, just a dozen feet above the cornfield. Funny thing, too. I went to sleep after that, right there. When I woke up it was dinner time."

"Oh?" I voiced, eyebrow raised.

"Oh, no!" she replied vehemently. "I'm certain I'm not an abductee."

"That's what I said. After all, you wouldn't remember it."

"I'm certain," she said so intensely that I decided not to challenge her. "And even if I am," she added, "I'd rather live with the belief that I'm not."

"Shit, I haven't thought of UFOs in years," Larry suddenly announced. "I saw one of those, too!" Then he laughed. "Just kidding!"

After awhile the four of us said goodnight. I passed Tony coming back from the porta-potty. "How's Anne's back?" I asked.

"She's in pain," he replied. "She's got some pain medication but at this rate she'll use it up before we get to Lake Meade."

"I thought Doctor Warren said it wasn't serious?"

"Him." Tony snorted. "You know what I caught him and his friend doing the last night before Phantom?"

"What?"

"Remember, we were up on a bluff. I went down to the river take a leak," Tony said, "and almost tripped on the two of them. Fucking."

"Oh, really."

"No shit. Could you ever think of anything more disgusting?"

"Uh, sleeping with Judy comes to mind."

Tony shook his head. "They should be shot. I can't think of anything more disgusting than one man sticking his dick in another man's ass."

"You usually seem so tolerant," I observed.

"Not about that, I'm not."

If I'd had any temptation to "come out" to the new passengers, that put a damper on it.

The evening quieted down; most of the passengers were in their tents and the bonfire had burnt down to embers and the boatmen were asleep on their boats. I stretched out in my sleeping bag in front of my tent, not in it, so I could watch the stars wheel slowly overhead. I was just dozing off when I felt a warm pressure over my collarbone.

Good evening, Arcadia, I greeted, though I knew the words wouldn't carry to her. Where the hell were you last week? I had no way of knowing. But I counted on my fingers and realized it was, indeed, Tuesday night back in the real world. I wondered how the Support Group was doing without me.

Before I knew it, it was morning. We had breakfast and set off down the river in our rafts. This time I shared a raft with blind Virginia and two others; Tony rowed. We had occasion to run a couple of sizable rapids that morning; I noticed that Tony ran them on a different route than the other boats took. Our run was more sedate; we didn't get splashed so much. I didn't say anything then, but when we stopped for lunch I asked Tony about it.

"I thought I'd better take it a little easy on Virginia," Tony admitted.

"But she didn't want that," I reminded him. "She said she didn't want special treatment."

"Sure, she said that," Tony agreed. "But that's because she has the illusion she doesn't have a handicap."

"Or perhaps you have the illusion that she does?" I suggested mildly. I really liked Tony for his humor and sometimes brutal honesty; but I was beginning to see he had a few hang-ups of his own.

We had enjoyed perfect weather so far and the day was gorgeous as we tied up the rafts at the mouth of a wide stream. The canyon walls at this spot were steep, and granite pillars created a faux gateway through which the stream poured into the river. We had to tie the rafts to fallen rocks, as there was no beach onto which to pull them.

Robby gave us permission to wander freely. So I found a little spot with a big rock and stretched out to enjoy the sun. Before long I was asleep.

I was awakened by the crash of thunder. A storm had moved in; the sky was heavy with rain. I knew that in these side canyons, flash flooding is likely; so I hurried back towards the rafts. In a couple of minutes the sky opened up, a torrent of rain coming down so hard I could hardly see. The smooth rock trail became slippery. Every now and then I encountered another passenger caught by the storm; we helped each other over the slicker stretches. Finally we were back at the river.

The walls of the Canyon looked like they'd sprung leaks. A dozen waterfalls gushed out of what appeared to be solid rock. Robby made a head count and, once we were all present, he directed us to jump into the nearest raft—not to worry about whether it was the one we'd arrived in. Carol and I jumped into one raft along with Turtle, who set it free. Immediately the current of the side stream increased, flushing us out into the Colorado. We hadn't gone far when a wall of brown water gushed out of our rocky little side canyon. The stream had flashed after all—but we were safe, on the main river.

But Carol didn't seem to realize that. She was crying, and every time a thunderbolt rocked the canyon, she cried and recoiled as if shocked.

"Are you all right?" I called over the din.

She shook her head. "I know it's silly," she wailed, "but I'm afraid of thunder!"

I tried to be helpful. "But, listen to it!" I begged. "The canyon corridors each have their own resonant frequency and the noise of the thunder is selectively amplified."

She stared at me as if I'd just been speaking Hindi.

"It sounds like the deepest notes of an organ, doesn't it? Isn't that cool?"

To her credit, she tried to hear it as I described. The thunder did, indeed, sound like the foot pedals of a church organ. She nodded, but then another thunderclap hit and she screamed again.

Not knowing what else to do, I put my arm around her. It didn't much help, but it kept us a little warmer. Later Turtle found a narrow beach to pull onto, and we located our own boats and put on our rain gear before continuing downriver.

The rain continued into the evening. The first suitable camping place we came to was on a vast slab of granite that lined the river's south side. The West Point guys insisted on putting up their heavy canvas tent and I assisted. "So, where do you know Rusty from?" I asked.

"Who?" Ted, Butch's personal physician, asked.

"Rusty, the baggage boatman. I saw him talking to you last night."

"Oh, the baggage boatman," the general repeated as though I had said, "the insignificant private." "Yes, he helped us put up our tent last night."

"We don't know him, thought," Will, the third general, corrected me.

"We wouldn't need any help putting it up, if it wasn't for my damned legs," Butch complained from the side. "We put up this tent all through the Korean conflict, and Vietnam, too."

"Technically," Ted corrected, "we didn't put up the tent in Vietnam. We had aides, remember?"

"You have AIDS?" I blurted, astonished.

"Not AIDS. Aides. Assistants," Ted corrected. He nodded in the direction of the boatmen, who were busily engaged in tying up the rafts, putting a tarp over the kitchen, and setting up the porta-potty. "Damnedest thing I ever saw," he said.

"What's that?" I asked.

"I've been watching closely. And I cannot see how Robby gives orders to his men."

"Orders? Robby?" I laughed. "He doesn't give orders. I mean, he's the trip leader but they all just know what to do. Each person just looks to see a job that no one else is doing, and he does it. Nobody has to order anyone."

"Trust me, young man," General Butch advised. "Any operation that runs smoothly has a chain of command. We've known this since the days of Alexander the Great—the first great human discovery, more significant even than fire."

The sides of the canvas tent were sodden. "Is this going to keep you dry?" I asked doubtfully.

"Of course!" General Butch assured me. "It kept us dry in Korea and Vietnam, two places that really know how to rain. For six months of the year it never stops! A little drizzle like this is no problem."

"And even if the tent does leak a little," General Ted added, "it won't matter because our sleeping bags are waterproof."

As it turned out, the sleeping bags may have been waterproof; but they no longer were. In the morning all three generals were shaking with cold and absolutely drenched. Robby, Rusty and I peeled the men from the soggy bags and poured hot coffee into them while Tony and Brian started a fire. Robby said they should strip; it was just a suggestion but they obeyed his every word as if it were a command from President Clinton himself. After the fired had warmed them, they donned dry outfits and their rain gear. It took ten of us to strike the soggy canvas tent and get it onto Cathy's baggage raft, weighing it down. Cathy glared at the generals and lashed it tightly to her oar frame.

The rain had stopped before dawn but the day remained cloudy and damp. To keep warm I asked to row more than I had previously. By now I was allowed to run rapids up to level 4 on the Canyon scale. This day Robby let me row eight miles, rapids and all, while he napped in the back of his raft. Virginia was one of the passengers, and she got a wetter ride with me than with Tony, since I had neither the skill nor the intention to find "drier" routes. We went where we went, and were damned lucky to come out upright, I thought.

That night clouds hung heavily overhead, seeming to swallow the beams from our flashlights. The passengers ate quickly and most retired to their tents. Even Rusty had disappeared. Carol, Matt, Larry and I remained on a damp bluff, our rain gear keeping our butts dry. In the distance we saw Virginia and her cane tapping about the beach.

Matt sighed. "I don't think it's right," he said, "to allow someone like that to come on a trip like this."

"She seems to be handling it all right," I pointed out.

"Not for her," Matt corrected. "For us. Whatever raft she's in, the boatman holds back. I want to get wet, I want to be scared. But my experience is diminished because she's with us."

"If it's the boatmen who hold back, then it's not her fault—it's theirs," I pointed out.

"She's coming this way," Carol whispered. And true enough, Virginia unerringly made her way to where we were sitting.

"Do you mind if I join you?" she asked.

"Please do," Carol urged.

Virginia plopped herself onto the sand and collapsed her cane down to the size of a pen. "Turn off your flashlights," she asked.

"Excuse me, but—how did you know they were on?" Matt queried.

"I can see glows," she replied. "Light and dark." We turned our lights off. "Now, wait," she directed. Puzzled, we did as she asked. At first, the night was utterly impenetrable; I couldn't see my hands in front of my face. Within a few minutes, though, I became aware of a faint grayness surrounding us.

"Talk about spooky," Larry said in a whisper. "This is almost as bad as a smoggy day in L.A."

"Look up," Virginia suggested. "What do you see?"

Above us the clouds were slightly lighter. Immediately above us, though, was a circular brightness—not very bright, but distinct enough that one couldn't deny its presence.

"A full moon above the cloud?" Matt guessed.

"No, the moon is new," I argued. "It set about the time the sun did."

"Venus?" Larry offered.

"Venus is never more than 28 degrees from the sun. You can't see it in the Canyon because the walls get in the way."

"What then?" Carol asked.

Virginia hesitated. "Do you believe in UFOs?"

"You're kidding," Larry said, as I asked, "Have you been talking to Rusty?"

"No, and no. When I was on my way to my tent I sensed it overhead."

"Sensed?" Larry asked, eyebrow raised.

"I know you've heard that blind people develop compensatory skills," Virginia stated.

"You mean, psychic skills?"

"In some cases. When I was a girl, I had normal vision. I was walking on our farm in Washington when I came upon a landed craft. I hid, and got as close as I could. When they took off, I was almost directly beneath it and got severe radiation burns. My parents found me and took me to the hospital. I healed except for my eyes. By the time the week was over, I could only see dark and light. But I began to develop other ways of seeing. And I always know when another craft is near."

"How do you know you know?" Matt asked, practically.

"By verifying it with others, such as you," Virginia replied.

"I'm not saying I believe in them," Larry said. "But if they're real, what are they here for?"

"I don't know," Virginia and I answered together.

"So," Matt said after a pause. "What you're saying, Virginia, is you're not really blind…you only present the illusion of being blind."

Virginia nodded slowly, her pale eyes reflecting the subtle glow from above. "I guess you could say that."

"And the boatmen are taking it easy on you because they've bought into that illusion."

"Have they?" Virginia demanded, suddenly incensed. "I suspected as much! —Except for you, Paul. When you were rowing I really felt as if I was in danger!"

"Greater praise no boatman could hope for," I responded wryly.

"So, there's—maybe—a flying saucer overhead," Larry said. "So what do we do about it?"

I shrugged. "What can we do? Just add it to the mystery that seems to be the lot in life for an abductee."

"I am not an abductee!" Carol insisted. Just then a crack of thunder split the night. There had been no lightning preceding it; we all jumped—and Carol screamed.

"Funny," I said, when she had calmed down. "The one night we get into a legitimate UFO conversation, and Rusty's nowhere in sight."

"Yeah," Larry agreed with mock suspicion. "And we can never find Clark Kent when Superman is around! Do you suppose…?" Mike groaned and Carol laughed shakily.

"Rusty isn't what he seems," Virginia announced. "I've only met him once, but that was my impression."

I kept my jaw set. I couldn't reveal my suspicions about Rusty without spilling the whole story about Arcadia.

There was another lightning-free thunderbolt and raindrops began to thud into the sand. A bobbing flashlight from the vicinity of the boats came closer and resolved into Robby and General Ted.

"Hey, Paul," Robby said. "I gave our spare tent to Butch and Will. Since you're the only passenger in a tent alone, I wonder if you'd mind sharing with Ted."

"Not at all," I said. "I'll show you where it is. I'm ready for bed anyway." I said goodnight to the others, led General Ted to my tent and crawled in ahead of him. He stuffed a sleeping bag through the opening—one of O.A.R.S.' sleeping bags, not his soggy Korean war model—and followed. After he'd wriggled in, I said, "So…how do you like the new sleeping bags?"

"They're amazing," General Ted replied. "I'm really astounded that the camping industry has gone so far past what we have in the Army."

"When I was in the Navy," I remarked, "I had the job of repairing radio equipment with parts that cost hundreds of dollars—but the radio itself could have been replaced for $20 by a unit from Radio Shack. Forget the defense industry; what you guys really need is good shoppers."

By day we continued downriver, playing in waterfalls, hiking the edges of sheer cliffs and in general doing everything our inner 12-year-olds desired. Ted and I shared a tent for the remaining nights to Whitmore Wash. He generally hit the sack before I did; I spent the evenings with Matt, Larry, Carol and Virginia discussing metaphysics, perception, illusion and reality. Rusty kept to himself.

One night we discussed hypnosis. When I mentioned that I knew how to hypnotize people, Virginia suggested I hypnotize Carol.

"Why me?" Carol asked.

"Because you have a bizarre fear of thunder," Virginia promptly replied. "Something must have happened to you to cause it."

Carol took a heavy breath. "I'd rather not know," she said.

"But knowing what it is could free you from it!" Matt pointed out. "Just think—you could go through the rest of your life, not fearing thunderstorms at all."

"It is tempting," Carol admitted. "But, in the end—I would have to recall whatever it is that's so awful my mind has suppressed it. Storms don't last. That memory, whatever it is, would. I'd just rather not know."

The last day before we reached Whitmore Wash, I rode with Tony. The canyon had opened up at this point, far-ranging vistas of rising hills having replaced sheer walls. Tony pointed to one of the hills. "It use to be," he said, "that whenever we came to this point, we could see the sun glinting off some kind of metal. So we used to say it was a plane wreck. One day, a group of government scientists reserved an entire expedition for themselves. No civilians, and we boatmen weren't allowed to talk to them."

"That must have been boring," I remarked.

"It made for a quick trip," Tony replied, "because we didn't do any hikes—just rowed. When we got here, the scientists told us to wait for them. They went hiking toward the metal. A few hours later, a helicopter flew overhead and landed in those hills. Only one of the scientists came back to the boats, and he told us to leave, that they were all flying out. We'd been rowing hard so we took our time. Just as it was getting dark, the helicopter took off with some kind of cargo lashed under it, wrapped in a black tarp."

"A flying saucer?" I guessed.

"I have no idea," Tony insisted. "I only know what I told you."

"Was Rusty on that trip?" I asked.

"Rusty?" Tony sounded surprised. "He doesn't really work for O.A.R.S., you know. He's just friends with George, the owner."

"But was he on that trip?"

Tony's brow furrowed. "Y'know…he might have been, at that."

That night Tony and Anne played some ‘60s rock ‘n' roll on their cassette deck while we danced. Turtle, who usually spent evenings in his personal space on his raft, drank a six-pack of beer and suddenly showed up on the "dance floor"—a level section of beach. To our surprise, he started break dancing! Whirling around and around on his forearms, spinning on his back, flipping over and over. The rest of us just got out of his way and stared in amazement. When the music ended we applauded. It was quite a display of strength, skill and talent. He staggered away from us, stood at the edge of the river, threw up, then returned to his raft.

We followed the dance with an impromptu talent show, featuring Mike's recitation of The Shooting of Dan McGrew and Larry's stand-up routine. I recited my mother's poem Pa And The Camera. Then General Butch, who had regained use of his legs, stood and praised Robby for his "outstanding leadership qualities."

"It's one thing," General Butch said, "for a man to direct his men by shouting instructions at them. It's quite another, and a rare trait this is, for a man to have so carefully trained his crew that they know what he wants them to do without having to say a word. So, 'General' Robby, we salute you!"

That night in our tent, I asked General Ted if he still thought that Robby "led" the boatmen in some sort of chain of command. "I listened to what you said the other night," he replied. "And I've watched. I think you're right. They all know what to do so well and they're so motivated that they truly don't need direction. But you'll never convince Butch of that. The chain of command has been his whole life. Real or illusion, he'll never see the world in any other way."

Just like Carol, who preferred her traumatic memories hidden. Just like Tony, who preferred the fantasy world in which everyone is heterosexual. Just like Virginia, whose illusion of blindness affected others no more than her own illusion of capability influenced her.

We all have our illusions, and they effectively screen the reality that lies behind them from us. Was my being an "abductee" also an illusion? And, if so—what reality was the illusion hiding?