| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/28/2024 Occurred: 4/1/1969 Posted: 1/5/2024 |

Page Views: 345 | |

| Topics: #Autobiography #Photography | |||

| Ny personal experiences with creating false apparent realities. | |||

When I was ten, I experienced a pivotal moment that set the stage for a lifelong fascination with photographic special effects.

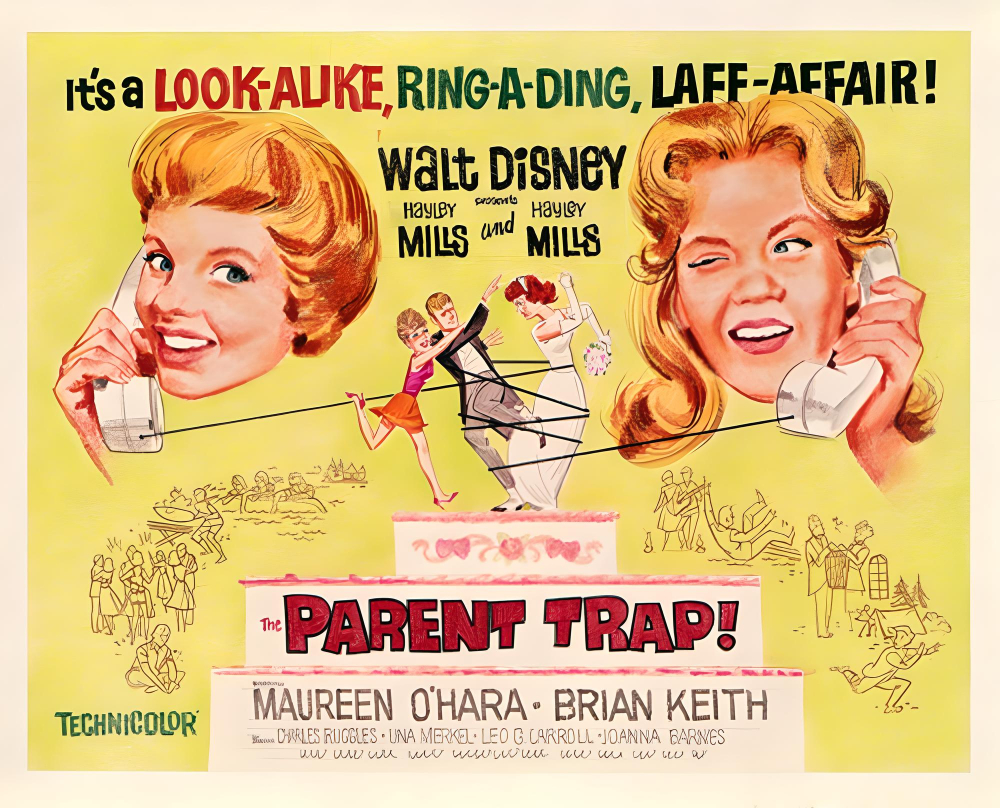

My grandfather, out of the blue, decided to treat my sisters and me to a movie. It was Disney's The Parent Trap,

ostensibly about divorce—a word I'd literally never heard before, but instinctively knew I'd better not tell

my mom—but blowing that aside was my astonishment at viewing two girls onscreen at the same time that

I knew were played by one actress. The advertisements and posters made sure we knew it: Starring Hayley Mills and

Haley Mills

! The sheer magic of seeing two identical Hayley Mills characters seamlessly sharing the screen was,

for lack of a better term, mind-boggling. I was captivated, utterly enchanted, not by the possibility that the same person

could exist in two places at once, but that they could, convincingly, appear to be.

At ten, I knew the difference between reality and film presentations. Three years earlier, when we first returned to Vermont after my father's death, I saw a movie on TV. I tuned in late and didn't catch the name of it, but I now know it was the classic Topper Returns, a 1941 comedy thriller about a ghost who enlists the help of a banker named Topper to find her killer. The film featured many in-camera special effects, such as invisible ghosts, moving objects, and trapdoors, that were inspired by the Universal Invisible Man films. The film was nominated for the Academy Awards for Best Special Effects and Best Sound Recording.

Now, considering my father had died just months before, and that my mother had to explain to me what a ghost

was,

you'd think that I'd have connected the two and asked uncomfortable questions. However, I didn't make the connection;

instead I was fascinated by seeing things on the flickering, black-and-white screen that looked real but I knew were

impossible…like the magically appearing footprints in soft sand, or the semi-transparent ghost of the woman

only Topper could see.

At seven I could become fascinated with the idea of creating a false reality. But at that time, I hadn't been permitted access to the camera. (I did sneak it out and took a photo of a tree, the summer before, but that film hadn't even been developed yet.

But then, at the more sophisticated age of ten, I not only had access to a camera; I had been elected family photographer. So as the credits rolled for The Parent Trap and the lights came back on, a spark had been ignited. The allure of in-camera special effects had taken root, and I found myself daydreaming about the endless possibilities that could be unlocked through the lens of a camera.

We had a Kodak Starflash, introduced in 1957. This compact and user-friendly camera became a popular choice for amateur photographers, offering simplicity without compromising on features. The Kodak Starflash boasted a fixed-focus lens, allowing for easy point-and-shoot functionality, making it ideal for capturing everyday moments. However, what truly set the Starflash apart was its ingenious protection mechanism against double exposures. In an era where accidental double exposures could easily mar a roll of film, Kodak implemented a foolproof system to prevent this common issue. The camera featured an automatic film advance mechanism coupled with a frame counter, ensuring that each exposure advanced the film precisely to the next frame. This thoughtful design not only simplified the photographic process but also safeguarded against the frustration of unintentional double exposures, making the Kodak Starflash a reliable companion for photography enthusiasts of its time.

However, in-camera special effects almost always require a double exposure. So, while the Starflash was an excellent beginner's camera, I soon outgrew it as a creative tool, though of course I continued to document family occasions and my second passion at the time, photos of the Florida jungle, with the reliable little camera. But I looked with lust at my grandparents' Kodak Duaflex.

My grandfather, who had been an optometrist, was of course fascinated by lenses; and he had a beautiful Kodak Duaflex that, I knew, did permit double exposures. The Kodak Duaflex, introduced in 1947, represents a classic chapter in the history of medium-format photography. This twin-lens reflex camera was designed to provide amateur photographers with an affordable and user-friendly option for capturing memories in a square format. The Duaflex's distinctive feature was its fixed-focus lens system, simplifying the photographic process for users who were not necessarily well-versed in the technicalities of focusing a lens. With its Bakelite body, the Duaflex was lightweight and durable, making it an accessible choice for enthusiasts.

The camera featured a unique, large viewfinder on top, allowing photographers to compose shots with ease. The Kodak Duaflex gained popularity not only for its functionality but also for its affordability, which made medium-format photography accessible to a broader audience. Its iconic design and straightforward operation contributed to its lasting legacy, making it a beloved vintage camera among collectors and photography enthusiasts alike.

Plus, it had a tripod socket in the bottom, something the Starflash lacked. Practically any in-camera effect requires the camera be rock-solid and unmoved between exposures; and that pretty much requires a tripod.

So, equipment set up, all I needed was a model. My mom was usually game for these things, and not a bad actress; so I got her to stand with a TV Guide on one side of the TV, and took the first exposure. But I also held a sheet of black construction paper in front of the camera, obscuring the half of the scene Mom wasn't in. Then, without advancing the film but moving the construction paper to the other half of the scene while Mom swapped sides, I took the second exposure. Here is the result:

It's not flawless; the camera did move slightly between shots. But considering it was my first attempt to do something Disney took months to perfect, and that I was by now about 15, I'd have to say not too shabby.

But by two years later, I had mastered the "ghost" effect, as well as time exposures for night shots. In the below photo, taken of myself and my friend Rosemary Hankins, the difference in light colors was not apparent when I took the photo; but it was a serendipitous accident that made the photo much more interesting.

Finally, another type of in-camera effect: One in which the filming is straightforward, because the film itself is special. Kodak’s infra-red film was a type of film that could capture the invisible near-infrared light that is reflected by plants, clouds, and other objects. The film was originally developed for military and scientific purposes, such as camouflage detection and vegetation analysis. The film came in both black-and-white and color versions, with the latter producing false-color images that had a distinctive and surreal look. The most popular color infra-red film was Kodak Aerochrome, which was introduced in 1942 and discontinued in 2009. The film required special filters, handling, and processing to achieve the desired results. However, without any special filters, most vegetation came out red instead of green, and the sky pink. Below is a shot of my sister, Mary, at Washington Oaks State Gardens.

In my senior year at St Joseph Academy, I branched out into literal cutting and pasting, and the effects weren't very satisfying. It turns out I'm much better at working digitally than I am with actual scissors and glue!