The place I work has occasional "morale-building" (read: non-compensatory) events. The one we're in right now is "shorts week". We can wear shorts to work, and T-shirts, and even sandals. Considering the outside temperature is above 110°, I would call this more "survival-enabling" than "morale-building" but, whatever.

Many of the employees here take these events very seriously. A co-worker, Ken, dressed for Carnival in Rio, demanded to know why I wasn't wearing sandals.

"I love wearing sandals," I assured Ken. "I used to wear them all the time. But my foot guy says they were drying out the soles of my feet."

"Your foot guy?" Ken repeated, puzzled. "You mean your podiatrist?"

"Actually, I don't have a podiatrist. My foot guy is a pedicurist."

Ken looked blank.

"He does pedicures."

Ken still looked blank, but gamely pushed on. "You get pedicures?"

"Trust me," I said drolly. "Getting pedicures is the best part of being gay."

Dempsey, my cubicle mate, choked on his coffee, laughing as it spurted from his nose. But Ken just cackled uncomfortably and left as quickly as he could.

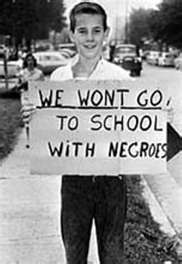

Ken is not homophobic. He just isn't comfortable enough around gay people to be able to joke about it. And I understand that perfectly, because I went through the same thing with a different minority group.

I saw black people for the very first time when I was about five years old. We lived in New Jersey, and once every few months my parents would go shopping at a department store called "Two Guys." I say my parents went shopping, because they always left my sisters and me in the car for the hour or two they spent inside.

It was a simpler time.

On one of these visits, my parents had returned to the car and my dad was just backing out of our parking space when he had to stop to let a family pass by. The family was black, but what I really stared at was how nicely they were dressed. (Even at five, I was gay.) The father wore a suit and tie; the mother wore one of those tight fifties skirts and jackets in two shades of violet; even their little boy wore a suit. Looking back, and considering that there were no other black people there, I suspect the family had gone out of their way to not give anyone an excuse to forbid their entering the store.

"Paul, don't stare!" That was my mother, in a stage whisper that could be heard in New York, using exactly the same tone she'd have used if she'd caught me gazing at a person in a wheelchair, or a pair of dogs humping. Mom came from the twin schools of "If You Don't See It, It Isn't Happening" and "If You See It, Pretend You Don't."

A couple of years later, on a day when I just did not want to walk down the street to my first grade class, I told Mom I didn't ever want to go to my school again. Mom explained that if I refused to attend Mount Virgin Elementary School, the law would force me to attend public school.

"So?" I asked. I had actually never heard of "public school" but was willing to entertain any alternatives.

"You wouldn't like it," Mom warned, clearly grasping at straws. "There are colored children there."

"Colored children?" I asked incredulously. Surely she was making this one up. "What color?" I was, of course, thinking of blue or purple or maybe green.

"Black," Mom said.

Oh, well. "I don't care," I said.

"You will," she warned. "Colored children smell funny."

Since the only "black smell" I knew was licorice, which I didn't like, I relented and finished out that year at Mount Virgin. But I saved that tidbit of information in that part of my brain reserved for Things I Don't Really Believe But I've Been Told.

I was ten when we moved to St. Augustine, Florida, a town that actually had a sizable black population. But in 1961 the black folks lived on one side of the railroad tracks, and we whites on the other. Whenever I actually saw a black person, he was a "yard man" or she was a maid. And, while my mother was always genuinely courteous, she still, unthinkingly, referred to grown black men as "boy". —Not to their faces, that I recall, thank goodness. But black adults were the only adults I was instructed to call by their first names, which made me very uncomfortable. I couldn't see any obvious reason for this exception to the "always call adults by their last name" rule.

Older kids in my neighborhood were not as tolerant as even my mother. Shortly after we moved in, I was walking with my sister when a strange boy challenged us. "Are you a nigger lover?" he demanded.

"A what?" I had never heard the term. Call it a sheltered life.

"Are you a nigger lover?" I still had no idea what he was talking about, but it was clear enough from his attitude that he intended to start a fight. My sister and I exchanged looks and high-tailed it to the house.

When I tried to ask my mother what a "nigger lover" was, she only got upset and wouldn't tell me. (That was the same approach she'd taken a few years earlier when she refused to define the word, "shit.") Eventually I worked out that the N-word was not nice and, from that, I developed an embarrassment about race. Not about people of different races; about the fact of race.

I just wouldn't talk about it.

By 1964, the turbulent civil rights years had come to our sleepy town. The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., visited. Black folks with picket signs walked back and forth in front of the Cathedral of St. Augustine during Mass; members of the congregation had to walk past them to go to church. Monsignor Burns invited them in, personally. But that wasn't the issue. Monsignor returned to the lectern, red-faced and furious. "As long as I am Monsignor," he swore, "I will never integrate Cathedral Parish School."

Despite his vow, the next year, four black kids joined my class. Some other kids integrated other classes, too. The world didn't end. And Monsignor Burns continued to be Monsignor.

But there are times when I think back to those days, and I can hardly breathe for admiration of the bravery of the kids who walked into our strange, white world. Ours was a small class and most of the students didn't mind integration at all; and the few who did—the ones whose parents did—kept quiet. But, still, going to a new school is scary enough. I had done it myself just a few years before. To attend a new school populated by kids who might hate you before even meeting you, must have been unbelievably terrifying. Yet the four of them, two boys and two girls, joined us, calm and dignified and brave.

The year passed without incident and, finally, it was time for our annual pre-summer class picnic. It was to be a pool party some fifty miles or so from school, and our teacher and school principal, Sister Trinita, asked for parent volunteers to drive us there.

My mother, who in spite of her 1912 birth date and quaint discriminatory manners, must have realized there would be a potential problem and insisted that I volunteer on her behalf. I was at that age where standing out in any way was utterly humiliating, but I saw it through—waiting for the other kids to leave the class, then making my way, red-faced, to Sister Trinita's desk.

"My moth—" I began, my voice cracking. I tried again. "My mother says to tell you, if they don't already have other rides, that we would be happy to drive Tom and Jim to the picnic."

The gratitude and relief on Sister's face was clear even to an eighth-grader. She took my hand. "Thank you!" she said. I'm still not sure if it was me she was thanking, or my mother, or, possibly, God.

So Thomas and James—I found out on the ride there that these were the names they preferred—rode with me and another boy, Dennis. When we got to the place where the picnic was being held, and everyone had gotten out of the car, I made a point of mentioning to Mom, "You know, they don't smell funny."

"What are you talking about?"

I reminded my mother of what she had told me all those years before. "I never said any such thing!" Mom insisted, and there was nothing I could say to convince her.

However, the fact remained that I probably blushed the whole trip to the picnic and back. Not because I was embarrassed to be seen with black kids, but because I was terribly afraid I would somehow make a fool of myself in front of them. I was okay as long as the conversation was utterly bland, but any reference to skin, hair, race, color or railroad tracks would bring the blood to my face.

After graduation, that summer, James was killed in a car accident. The whole class attended a memorial service for him…in the Cathedral.

High school at St. Joseph Academy held its usual angst for all of us, but as far as I know it wasn't any worse for the black students than it was for the whites—with two exceptions. (Remember, these are just the events I know about.)

Thomas had grown into a well-built young man who excelled on the football field as well as the basketball court. However, we were in the deep South, and on one occasion, Coach Drozd brought the team together and I, though not on the team, managed to overhear. It seemed the team we were scheduled to play that night had "just discovered" (!) that there were black players on the team, and they would not play us.

The white kids on the team immediately, and unanimously, declared that if their black teammates couldn't play, neither would they. Thomas then urged them to play, anyway—and win.

Which they did.

In football season, after the big "Potato Bowl" game against our rivals at Hastings High—another game we won—we stopped, the whole team (I was team photographer) and their families, at a hamburger joint for a celebratory meal on the way home. I was sitting with Thomas and his older sister Barbara when some Hastings toughs walked to our table and began swearing at Thomas and his sister. These guys were football-player size; I couldn't reasonably have taken them on but I never got the chance because I sat in shock during the entire exchange. The fact that I was experiencing racial prejudice hadn't even registered; I was immobilized by the appalling rudeness of these people.

Thomas and Barbara, apparently used to this sort of thing, never rose to the bait, determinedly ignoring the racists with quiet dignity. Consequently, no one around us even knew there was a problem—and I'm sure the racists had no clue they were surrounded by a victorious football team of which Thomas was a member and who could have easily handed their asses to them in a paper bag.

They left about the time Coach Drozd came charging up, possibly having caught the situation out of the corner of his eye. "Are those boys giving you any trouble?" he demanded.

"No Coach, it's okay," Thomas said.

They said the 'N' word, I wanted to say, but I was frozen in horror. This really was the first time I'd encountered mindless, bigoted hatred and it literally made me nauseous. For yet another time I was amazed at Thomas' bravery. —And at Barbara's as well. Dimly, I began to perceive that simply being black made demands on a person that a white person might never understand, demands that would either destroy a person, or make him or her unbelievably strong.

Deep down, I felt that by not speaking up I had been as guilty as the racists. I swore I would never sit quietly through such a display again.

I can't say that Thomas and I were really close friends—he was a jock and I was a nerd and we didn't really have much in common. But Thomas' family practically adopted me. As the school photographer, I needed to find a place to develop film. Thomas volunteered his father, who (among other things) was a professional photographer. Mr. Jackson took me under his wing, teaching me as much as he could about photography, film developing, print making and more. With my own father dead, and my grandfather crippled and in his eighties, Mr. Jackson became more a male role model to me than any other I had.

One day, waiting for her husband to come home from work, I sat with Mrs. Jackson as she prepared dinner. She chatted and casually remarked, "I was talking to a white woman at the A&P this afternoon, and she said…" I have no idea what the woman said, because until that moment I had never heard color prefixed to a person's description unless the person was not white. It was a revelation to realize that, to a black person, black was "normal" and white needed definition!

Then there was the time that Mr. Jackson casually showed me how to make a good-quality print of a group portrait in which some members of the group were black while others were white. "If you expose the paper for the white faces," he explained, "the black faces will be too dark, and you won't be able to see anything but eyes. But if you expose for the black faces, the white faces will be too pale and, again, you'll only be able to see their eyes."

Fortunately we were in a darkroom, and he couldn't see me blush. —Because the topic of race had come up.

"So what do you do?" I asked, furiously trying to focus on the issue at hand.

"It's called dodging and burning," Mr. Jackson replied. In the darkness, he pointed at the negative image of the football team projected dimly on the raw photographic paper. "If the crowd is mostly white, on the negative their faces are darker. Expose for them but during a fraction of the time you expose the paper, cover the faces of the black folks with your thumb so they don't get quite so much light—that way the paper won't make them so dark. Or, if the crowd is mostly black, make it a shorter exposure, but then cover everything but the white faces and give them a little more light, so they become darker."

Eventually, I realized that the essential embarrassment came from my not being able to use race as a joke. To me it wasn't funny; and that was because I was caught in the dichotomy between people for whom black was "bad" and others for whom black was "normal". After all, I made fun of everything else.

When I finally got past being embarrassed by the fact of race, it was because I finally realized my black friends were comfortable simply being themselves. I even know the day it happened. I was in junior college, seated in the student commons with perhaps eleven other kids, two of whom were black. One of the black kids, Jerry, had a very nice, chocolate-colored suede jacket with fringe, and Jim, one of the white guys, complimented him on it. "I have a jacket just like that," Jim added, "except mine is flesh-colored."

I snorted. "So is Jerry's," I pointed out, tartly. And everyone laughed, including Jerry and Jim. Score one for gentle racial humor!

Now, through all these years I also heard nasty things said about "queers" and the fact of sexual preference—which I understood far less than I did race—also became a source of embarrassment. And I have to assume that other people my age had similar experiences. But without good, solid models of what a gay person can be, they were as uncomfortable with the idea of gender preference as I would still be uncomfortable with the idea of race if the Jacksons hadn't been so kind as to spend time with me.

It isn't enough to be "out" as gay. Any black person is "out" simply by virtue of his or her appearance. But it's in the normal interaction of everyday life that we become comfortable with each other. The same is true of interaction between straights and gays; it doesn't do any good for the gay person to "act straight" (whatever that means), any more than it would have been helpful for my black friends to pretend they were white. There are cultural differences between American blacks and whites; and there are cultural differences between American straights and gays. Few straight men will get their feet done by a pedicurist, for example, just as few gay guys will get a cartoon of a hula girl tattooed on their biceps. Only by being comfortable with our differences, by joking about them, can we relax to the point that we can simply accept them with no rise in blood pressure.

A few years ago, I worked in a bullpen with several people who were rowdy, obscene, and very, very funny. These people were so comfortable with themselves, that they had no need to force anyone else to be any particular way.

One guy in particular, Todd, would make the most delightfully obscene references to everyone—in the group, on the phone, whatever. What made his jokes funny was that they were never mean-spirited; they were simply startling in their bawdiness. For example, when one of the guys showed up wearing glasses for the first time, Todd clucked and said, "Thank God you stopped masturbating before you went blind altogether." Just out of the blue. Funny.

Since they knew I was gay, I had pretty much given up hope of being accepted in the same rowdy, masculine way. But one day we were having a meeting about a program I was writing, and our supervisor expressed some security concerns. "Can't you write a 'back door' into the program?" he asked, referring to a secret way to make the program function without a password.

"Sure, he can," Todd immediately spoke up. "Gay guys know all about back doors."

I had been swallowing some Diet Coke when he said this, which I immediately spit onto my shirt. The supervisor was horrified, no doubt certain that I was going to sue the company over sexual harassment. But I was delighted. By being relaxed enough to joke with me on that intimate level that straight guys use when they work together, Todd showed that our difference in sexual preference didn't need to be divisive.

I think any time you have tolerant yet diverse people encounter each other, there's going to be a period of discomfort—not with the actual differences, but with the fact of difference. That's the most exciting time, when everything about the other person is new and ready to be explored; but it's also an awkward time, because there's no way to guess what innocuous detail will turn out to be offensive, embarrassing or just plain annoying to a person of the other culture. (I remember with chagrin the times I used the phrase "whip them into shape" without having the slightest clue it was a reference to slavery—I thought it had to do with creating a meringue!)

It's after that period has passed, when the relationship has reached the point where people who joke can joke, and people who don't, don't have to, that things get easy and comfortable. If you are dealing with a transient culture—say, the Gypsies have come to town for a of couple weeks—things can stay at the exciting level. But when a culturally distinct group has come to stay—like whites and blacks and men and women and straights and gays and Irish and Hispanics and Italians—the only hope for a relaxed, workable, long-term relationship is get things to the point where they're as easy as Sunday morning.

Somewhere between dodging and burning, is simple acceptance of the fact of difference.