| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/19/2024 Posted: 3/15/2007 |

Page Views: 4392 | |

| Topics: #Photography #DigitalPhotography | |||

| How to digitize your photo and slide collection before the pictures fade any further. | |||

Chances are, somewhere in your home, you have a row of photograph albums on a shelf containing photos of your childhood, the births of your children, your vacations and graduations and proms—and that haven't been opened in years. Or you may have box after box of color slides, carefully inserted into slide trays even though you couldn't put your hands on the slide projector if your life depended on it.

Even so, you know they're there; and that alone can spark a memory of a treasured photograph or a particularly beautiful slide.

But are they there—really? The dyes that make up color images have been fading in the years since you had them developed, causing color shifts (where the yellows, for example, remain bright but the other colors fade, leaving a strong yellow cast to the image). Black and white images are more stable, but even they fade with time; and both color and black and white negatives are prone to damage from dust and scratches, and some color slides actually attract colonies of fungus that can obliterate a priceless picture.

What's a photo lover to do?

Until a few years ago, nothing could be done. But now your photos and slides can be digitized, meaning they can be turned into computer files, in which form they can never discolor or become scratched or infested with fungus. The common name for this process is scanning.

But what if you aren't particularly fond of computers? Well, that's what this essay is here to address. 'Cause you probably have a computer, or plans to get one, or a relative with one. And this job has to be done now, before your precious photos can deteriorate any more than they already have.

The first step is to gather your photos together. Clear a table, and bring those boxes of slides in from the garage or hall closet, those albums from the bookshelf. You're especially fortunate if you still have some (or all!) of the negatives that made the prints in those albums, because negatives contain more information than prints, and can usually make higher-quality scans.

Next, organize your photos by decade—this will help both to break the work of scanning into manageable pieces, and to assist you in organizing the scanned image computer files when you have them.

Now you have to decide: Who will scan these? If you don't own a scanner, the answer is simple: Someone else! But even if you do have a scanner, you may chose to farm out at least part of the work.

The reason is that high-quality (and high-priced) scanners exist that do especially effective jobs, not only of scanning slides and negatives, but of repairing them as they are scanned! Such scanners make use of what is called Digital ICE (Image Correction and Enhancement), a set of technologies that locate imperfections in a color image and compensate for them. For example, a dust mote can be hidden by interpolating the picture around it, so that a good estimate of what the mote is covering can be generated automatically, making the dust mote effectively invisible. The same thing can be done with scratches. Unfortunately, Digital ICE currently can only be applied to color negatives and slides; but since the majority of photos take one of those two forms, that's a great help right there.

Now, you can certainly buy a scanner that incorporates Digital ICE; many hobbyists do. Just remember:

It will only be cost-effective if you have thousands and thousands of negatives and slides to scan.

There's a learning curve involved in discovering how to make optimal use of such a scanner.

It takes a lot of actual time to do the scanning, especially of that many photos.

So, it may be to your benefit to send your slides and negatives to a professional for scanning. There are many such places listed on the Internet (Google "scanning photos negatives"). Make sure you see "Digital ICE" somewhere on their web site. I cannot recommend using a drugstore or discount store service, as I have always gotten inferior results. (I use Memories Renewed, and have always been happy with their work. Once you find a place that does a good job for you, you tend to stay with them.)

If you've kept your negatives, you probably have the prints as well. Keep them aside for emergency use: If a negative is particularly damaged, or missing, you can still scan the print.

You can farm scanning your prints out as well, but Digital ICE doesn't work on prints so there's no real advantage to doing so if you have a standard scanner. (Good scanners can be purchased for well under $100.) In tomorrow's essay I'll cover what you need to know about scanning.

I recommend you do the scanning of your pictures in batches. That keeps both the cost, time, and scope of the job from overwhelming you. If you've been able to organize your photos into decades (or even years!), so much the better—just let a decade equal a batch and get on with it.

Having cleared your table to accommodate the original photos, slides and negatives, you'll also need a place in your computer to store the digitized versions in. If you are using the Microsoft Windows operating system, you already have a My Pictures folder (it's a subfolder of My Documents). Users of other operating systems can simply make one.

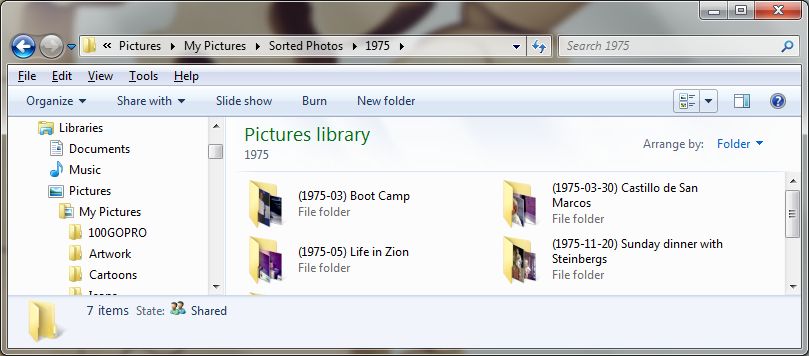

Within My Pictures, I recommend creating sub-folders for each year; it makes individual pictures so much easier to find later. In some cases, for example Grandma's old tintypes and early photos, it may be more practical to name a folder for a range of years. In my case, I have folders named 1850-1950, 1951-1957, 1958, 1959, etc. (I was born in 1951; hence the division between the pre-Paul pictures and the with-Paul pictures.)

Within each of the year folders, I create further subfolders for dates and events. For example:

Notice the formatting for the date: YYYY-MM-DD. This will automatically sort the folders by year, month and day. Also notice that I don't always know the exact date; I can usually narrow it down to a month, though, based on whether there's snow on the ground or the trees are turning or other clues. Generally, people work their way through a roll of film, taking several pictures at once and then several more days or weeks earlier. If your photos are still in the original envelopes from the drug store, they are chronological but grouped by film roll. Now, in the computer, you can more logically group them by event.

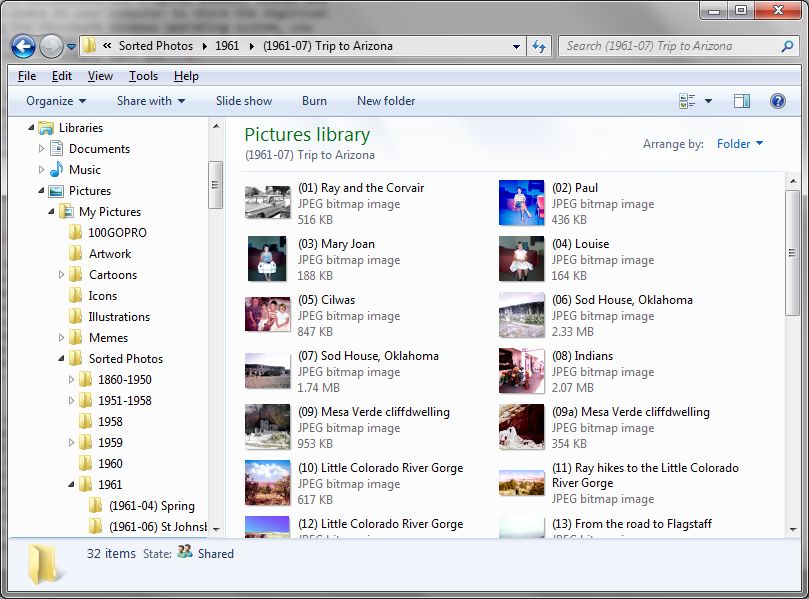

Whether you farm out part of the job or not, your images will come back to you with meaningless names (such as "Image00002" or "Pic032"). It's unlikely that the numbering scheme will have any relevance (I'll explain why tomorrow, but take my word for it, for now). So you really are going to need to name each photo. I recommend using descriptive names, and where people are in the photo, I use their names in a right-to-left, top-to-bottom order. It isn't necessary to repeat the date of the photo if it's in the folder name. But I do recommend preceding the descriptive name with a number (which I put in parentheses). This is for the dual purpose of ordering the photos, and allowing the same description to be applied to several photos in the same folder.

For example, if you visited, say, Grand Canyon and took 20 photos of it the same day (not at all unreasonable), odds are you don't really remember what, exactly, each photo is of, in spite of the fact that each peak and valley in the Canyon has been given a name. That's fine. You might have the following names in the folder:

The leading zero in the number is to allow proper sorting of two-digit numbers. If, for some reason, you have a hundred or more photos in the same folder, you'll need two leading zeros in the beginning, to allow proper sorting.

If you do your own scanning, you can either place the scan files directly into the appropriate folder, or into a "work folder" for safekeeping until you can perform final corrections on the picture (repairing scratches, adjusting color, cropping, and so on). I don't recommend you let the work folder get away from you, but there is a logic in doing a bunch of scans, then a bunch of corrections, followed by the final placing of the images in their destination folders (which you can think of as "albums").

It is possible to append additional information to your scanned photo files. File Metadata is a relatively new concept that allows supporting data to be physically attached to a file, without changing its basic binary format. There are several stand-alone programs that allow you to append this information on a file-by-file basis, as well as the newer photo editing programs that we'll be discussing tomorrow. (In addition, some of this information is supplied by high-end digital cameras.) This information can identify where and when a photo was taken—even to latitude and longitude, if you know it—and allows lengthy descriptions, such as the fact that Aunt Lou was your dad's favorite sister, or what your mom was actually getting out of the medicine cabinet that caused her to have such a horrified expression when you surprised her with the camera.

While you're at it, don't miss the opportunity to scan other images that may be deteriorating, like pictures you or your kids drew or even ticket stubs or other items you might normally have placed in a physical album. Believe me, the image of your ticket to that 1977 Little River Band concert will evoke as much emotion on your computer screen as would the yellowing stub itself, and will last longer.