| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/24/2024 Posted: 3/28/2007 |

Page Views: 4111 | |

| Topics: #DigitalPhotography | |||

| Learn how photos are displayed on a computer screen by comparing to embroidery. | |||

In previous posts, I've vaguely described digital photographs (including scans of traditional photos) as being broken into a great many pieces, with a numeric color value assigned to each. That's the substance of a digitized photo. But since you are going to need to deal with computer files containing these photos, and there are several popular formats for these files, we're going to have to understand what forms these files take, at least, at a high level. I could simply list the file formats and ask you to trust me. But I think it's a lot more interesting if you know—at a high level—what's going on inside.

To begin with, please imagine some of the needlework embroidery you may have seen your grandmother do. One form of this embroidery is called cross stitch. Here's an example:

This is a very simple cross stitch pattern, shown to reveal the fact that the cloth is printed with faint squares, onto each of which may be sewn a simple X in one color or another. My Aunt Edna always used checkered gingham for her cross stitch work, but any material in which a grid can be utilized by the embroiderer will do. And don't underestimate the complexity of pictures that cross stitch can create; here's a more impressive example:

If the squares that make up the grid are small enough, and sufficient distinct colors of thread utilized, and the embroiderer patient and skillful enough, any picture can be cross stitched—even one photographic in its detail.

In the 1970s an alternative approach to displaying graphical information was tried by the company Tektronix. Instead of working the way televisions do, the Tektronix computer terminal bore a screen that retained an image that was drawn on it with an electron beam.

In computer terms, that grid, with each square assigned a color, is called a bitmap. The bitmap is the basis of all computer graphics; and every other type of graphic must resolve to a bitmap in order for it to be displayed.

When creating cross stitch embroidery, the size of the squares directly addresses the degree of detail in the finished result. This equates to PPI (pixels per inch). Another factor in a bitmap is the color depth, which, keeping to our cross stitch analogy, compares the number of different colors of thread the embroiderer is using.

The physical space taken up on your hard disk by a bitmap depends not only on its two-dimensional size (resolution), but on its color depth. For example, while a monochrome bitmap only requires one bit per pixel (one bit can represent "black" or "white"), a sixteen-color bitmap requires four bits, and a full-color (photographic) bitmap requires at least twenty-four! That means that a full-screen, 800 * 600 pixel, full-color bitmap, requires about 1.3 megabytes of storage! (And today's larger screens and higher resolutions need even more.) It is possible for a program to calculate how many distinct colors are actually used in a bitmap; and in the days when the raw bitmap file formats were in common use, that was often done to save space. However, there's a better technique now.

Raw bitmaps are uncompressed files, which means that if the finished bitmap takes up 1.3 megabytes, the file will take up a little more space than that on the disk.

For comparison's sake, here's a bitmap of a Valentine's heart:

Here's our heart graphic reduced to just 256 colors. You can see that the glow and shading around the heart is slightly less subtle than in the full-color version, but not objectionably so. Yet, as a bitmap, the second version takes one-third the space of the first!

Even more space could be saved by dropping to 16 colors, and using a technique called dithering (the same technique that is used by magazines when they print a photograph). As you can see below, the results are inferior to those of the fuller-color versions; yet the intent of the graphic remains. And in some cases, reducing to sixteen colors—especially in the case of a cartoonish-like figure like this one—results in no visible deterioration of the image at all.

However, full-color, natural photographs did suffer from such compression. And, although this file format worked fine on home computers, it was far too large for Internet connections—especially when those connections were made over telephone lines! You could have a cup of tea while waiting for the transmission of one picture to complete.

Before everyone was on the Web, there was CompuServe, an online service which made use of the LZW compression algorithm to form the Graphics Interchange Format (commonly known as GIF). Although CompuServe at first claimed exclusive proprietorship of this format, the LZW people took them to court; and now the official position, in the words of CompuServe's vice president, is that "CompuServe is committed to keeping the GIF 89A specification as an open, fully-supported, non-proprietary specification for the entire on-line community including the World-Wide Web." So, there!

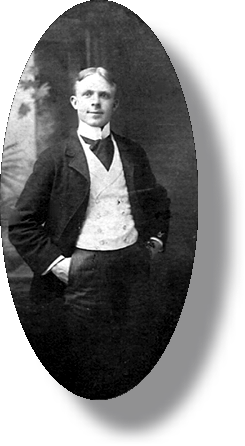

The GIF specification allows only a 256 color palette, so it is generally better for drawings and cartoons than full-color photographs. It is compressed, but not lossy. Its main feature, though, is that GIFs can include a transparency channel, that is, an extra bitmap that indicates which cells are to be transparent and which will come from the graphic, itself. The transparency channel is just one bit wide; so a given cell is either transparent or it is not. That allows for limited subtlety in the graphic. But since black and white bitmaps never use more than 256 levels of gray, and many old photographs were mounted in non-rectangular mounts, the GIF format is a natural for irregularly-shaped, older photos because it allows a background to show through the transparent areas:

My grandfather, Vernon Brown, in 1897

Now, with all that said, the most common file format for photos on the Web, is called JPEG (pronounced jay-peg, and and usually has a .jpg extension).

JPEGs (extension .jpg) are a compressed, "lossy" format for storing photo-quality images. "Compressed" means they take up far less space than a bitmap; "lossy" means this is accomplished by not storing every single bit. If you repeatedly load and save a JPEG image, it will become more and more "washed out", like a copy of a copy on a Xerox machine. However, the degree of lossiness is controllable; you can choose lossiness over size to obtain the smallest possible file without losing so much quality that the image becomes unusable. I used to save my photos at 95% quality (5% compression). For web use, I dropped to 85% quality. Few people can tell the difference. Nevertheless, I now save my jpgs at 100% quality. They are still a manageable size; and since most web viewers have high-speed Internet access, there is no noticeable increase in download speed.

JPEG is short for Joint Photographic Experts Group. This is a group of experts nominated by national standards bodies and major companies to work to produce standards for continuous tone image coding.

JPEGs are always stored with a full palette of 16,000,000 colors; but they have the attribute of being expanded into however many colors are available. In other words, if you display a full-color JPEG on an old computer that can only display 16 colors, the JPEG expander will automatically dither so that the result is the best possible for the display.

There's a couple of other formats you should know about. TIFFs can be compressed by an optional lossless algorithm; they are used when absolutely optimal quality is required (for example, by professional printing houses). TIFFs therefore may take up less space than equivalent bitmaps, but still more than equivalent JPEGs.

PNG (short for Portable Network Graphics) format files are compressed and lossless with the added advantage of supporting 256 levels of transparency, which allows for subtle drop-shadow effects GIFs can't support. Since the PNG format is newer than JPEG, not all image editing software supports it. All the newest Web browsers do, however, which enhances your ability to be creative in the Internet environment if you wish to take advantage of it.

Here's an example of a PNG with a "shadow", superimposed over a background. What you see will depend on the age of your browser. (Internet Explorer 7+ displays PNGs correctly.)

My grandfather, Vernon Brown, in PNG format (with a shadow).

So, what should you order when you get your slides and negatives scanned? I ask for high-quality JPEGs, which are less expensive and take up less space. Even though the format is lossy, it doesn't lose very much—nothing you can spot, really. And I convert them into bitmaps before working with them, so I can open, edit, and close them repeatedly without losing any quality each time. (I may make a pass to crop a batch, then a separate pass to color correct, and another to retouch dust and scratches, etc.) When I'm done, I save them as high-quality JPEGs.