| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/16/2024 Posted: 3/14/2007 |

Page Views: 5438 | |

| Topics: #History #Photography | |||

| A brief tour of the processes and inventions that led to today's digital photographic revolution. | |||

It wasn't that long ago—two centuries or less—that ordinary people simply had to rely on their memories to recapture their pasts. Prior to 1790, anyone who wanted a visual representation of a person or event had to commission a painting of it—a relatively expensive proposition, and one which did not guarantee accuracy, if the artist had not been present at the event or did not personally know the subject. (For example, the iconic painting of Christopher Columbus that identifies him in most schoolbooks, is known to be inaccurate. The portrait, by Sebastiano del Piombo, shows Columbus with dark hair; but his contemporaries described the younger Columbus as a red-head, and as a man with white hair as he aged.)

In 1790, Americans joined the world-wide craze for silhouettes, those outline-only images that can capture a person's essence, without actually including any facial features or expressions. Named after Etienne de Silhouette, a finance minister of Louis XV who in 1759 imposed such harsh economic demands upon the French people that his name became synonymous with anything done or made cheaply, they were created by silhouette artists in a few minutes, with only paper, scissors and glue, and were thus quite inexpensive. However, they were practical only for representing people known to the artist.

That all changed with the appearance of the camera which, while technically invented as early as 1685, wasn't practical until Jacques Daguerre's popular daguerreotype process came along. The daguerreotype took advantage of the fact that a combination of exposure to light and certain chemicals could darken crystals of silver halide. Those particles were deposited upon a silver mirror and exposed to light focused through the lens of a camera—a lightproof box containing the unexposed daguerreotype plate at one end and a shutter and lens at the other—for a predetermined time. The plate would then be removed (in a completely dark environment) and held over a pan of heated mercury, so that the mercury vapor chemically bonded with the silver halide—but selectively, as more mercury bonded to the silver halide crystals that had been exposed to the most light (the brighter areas of the photo, such as that reflecting off a lady's white dress or a man's white shirt). The mercury was then removed, which left the darkened crystals where the dark areas of the photo (a man's coat) were, exposing the bright mirror backing in the lighter areas. Thus, the image was a positive. "Fixing" it in a solution of hyposulphite of soda—known to photographers today as "hypo"—made the image impervious to further alteration by exposure to light, so that it could be viewed.

Louis Daguerre had patented his invention in Great Britain; he closely controlled the patent and sued anyone for infringing on it, as did his successors. Consequently, the process never caught on in Britain. In the United States, where it was unprotected, the process caught on like wildfire; soon, every tourist community featured at least one daguerreotype parlor and traveling photographers brought the process to the hinterlands. Anxious to preserve the images of their loved ones (in an age with high child mortality), entire families would line up to be photographed when the daguerreotype man came to town.

But these images were extremely fragile. The only ones that survive were sealed behind glass in an inert atmosphere (generally, nitrogen). In 1856 daguerreotypes were made obsolete by the invention of the ferrotype, more commonly (though inaccurately) called the "tintype". Tintypes were sturdier than daguerreotypes, and exposure times were briefer as well. The daguerreotype shops quickly adopted the new technology. The odds are you, dear reader, own a few tintypes passed down from your grandparents.

In 1850 a process known as "wet plate" was developed. It was inconvenient (the plates had to be prepared just before use) so the tintype shops left it alone. However, the amount of detail and subtlety that could be captured by this process, made it irresistible to those who were more attracted to the art of photography than its lucrative aspects. This process produced a negative image of a scene, from which many positive images (negatives of a negative) could be produced. In 1861, Mathew Brady, a Washington, D.C. photographer, organized an army of photographers to go forth and capture the Civil War on film. His historic images still evoke the horror and futility of war.

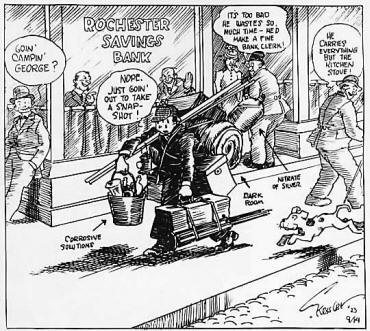

Wet plates used a glass substrate, as did the greatly improved dry plate process which followed, in which the silver halide was suspended in a gelatin rather than a collodion. Professional photographers (and ardent hobbyists) were the only people who could take such photographs, and our view of the world of that time is one seen through their eyes. But, in 1884, George Eastman took the basic dry plate process and, instead of adhering the gelatin to glass, adhered it to a flexible film instead. That film could be wound into a roll; the camera for amateurs had been invented. Eastman, a marketing genius, created the Kodak company to manufacture and distribute his cameras with this delightful concept: The camera was purchased with enough film inside to take 100 circular photographs. When the last was taken, the entire camera was returned to the company, which processed the film, and returned the re-loaded camera and prints to the owner.

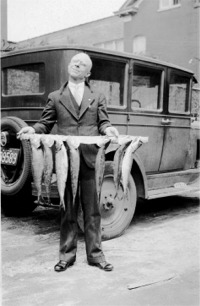

From that time on, photographs show the world through the eye of the average person. As might be expected, many such photos have little significance. Fortunately, most shots of the floor, the ceiling, and the very blurriest images were generally thrown away, leaving images that show a day long gone. Not only did such pictures serve as reminders of the near past—what Aunt Edna looked like when she was young, that young man mother met on vacation who later accidentally broke his neck and died—they have lived past their original purpose, now giving us an insight not only into the appearance of our ancestors, but a look at the way they lived: Their homes, their horses and cars, their recreations.

Moreover, people often take vacations in famous places and they always take their cameras with them. Thanks to the vacation photos of the past, we can chart the changes to Grand Canyon, the erosion of Niagara Falls, any alterations made by increases in visitor numbers to Yosemite. We can see the effects of erosion on the beaches of Florida, the no-longer-in-service train to Key West, the cumulative results of air pollution on statues in New York and Washington and Mount Vernon.

However, we are in danger of losing all this past. While the oldest photographic prints and negatives have lasted a long, long time—they are breaking down. And newer photos, those taken in color, are losing their integrity even faster. Photos taken in the 1960s have faded to the point that most of the color is lost; even color negatives, which are typically stored in the dark, exhibit severe color shift. And Ektachrome color slides have turned out to be subject to fungal infestations that, with time, can completely obliterate the image.

What can be done to preserve this heritage?

Fortunately, a completely new technology has come along that makes saving these images possible. Digitization, a process by which a photograph can be broken into millions of minute pieces, with a numerical value assigned to each that indicates intensity and color, can analyze a photograph and store it indefinitely with no possibility of information loss. You know this process as "scanning" and, if you are reading this on your computer, you probably own a scanner yourself.

Next we'll examine options for preserving your precious photographs so you can pass them on to your children, grandchildren, and anthropologists into the centuries to come.