| By: Mark Twain | Viewed: 4/16/2024 Posted: 2/21/2007 |

Page Views: 5461 | |

| Topics: #Spirituality #Metaphysics #MarkTwain #Synchronicity #Telepathy | |||

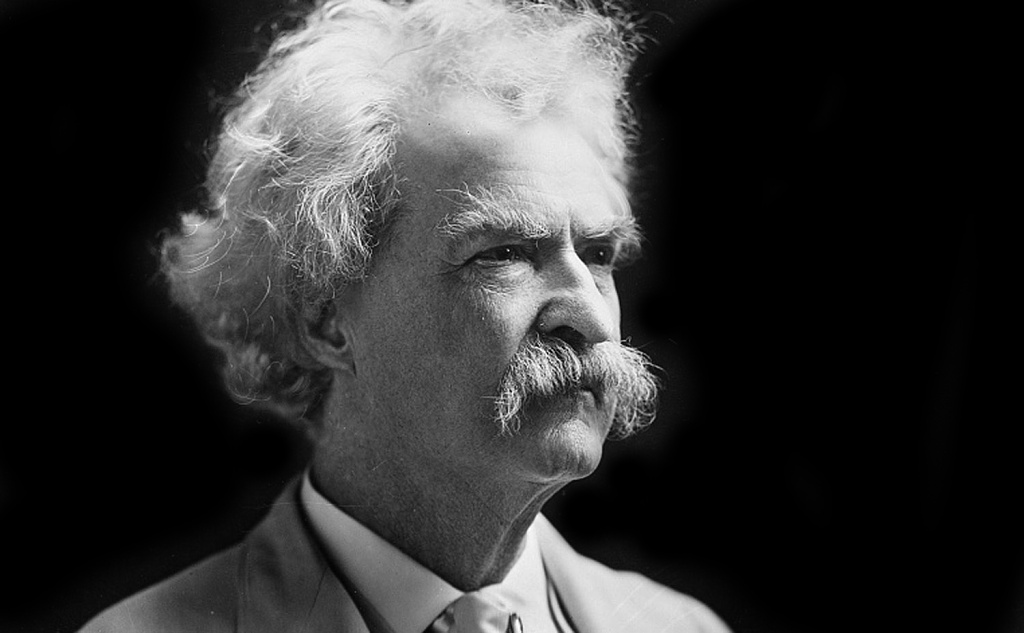

| Famous writer Mark Twain noted the existance of what we now call 'telepathy', and how to make it happen intentionally. | |||

One of my very favorite writers is Mark Twain—real name, Samuel Clemens, of course. Among his voluminous writings, are several serious pieces he wrote about what he called "mental telegraphy" (and we now call telepathy).

The pieces were serious, but because Twain's reputation was that of a humorist, he didn't want them published under his famous nom de plume; and as he wrote to a publisher,

I tried to creep in under shelter of an authority grave enough to protect the article from ridicule—The North American Review. But Mr. Metcalf was too wary for me. He said that to treat these mere "coincidences" seriously was a thing which the Review couldn't dare to do; that I must put either my name or my nom de plume to the article, and thus save the Review from harm. But I couldn't consent to that; it would be the surest possible way to defeat my desire that the public should receive the thing seriously, and be willing to stop and give it some fair degree of attention. So I pigeonholed the manuscript, because I could not get it published anonymously.

These are the pieces referenced by Robert A. Heinlein in Lost Legacy, when he stated that Twain had written about telepathy and even told how to do it, but that people only laughed. I intend to reprint these essays here over the next few days, for it's been far too long since they were seen in the light of day. But please, as you read these words that are over a hundred years old, consider: Since they were, indeed, published—how is it that, even now, the mainstream media makes light of the very kind of incidences Twain describes?

—Oh, by the way—in editing these pieces, I have modernized the spelling and, in one or two peculiar cases, the grammar; but otherwise these are Sam Clemens' exact words, just as he wrote them.

May 1878

Another of those apparently trifling things has happened to me which puzzle and perplex all men every now and then, keep them thinking an hour or two, and leave their minds barren of explanation or solution at last. Here it is—and it looks inconsequential enough, I am obliged to say. A few days ago I said: "It must be that Frank Millet doesn't know we are in Germany, or he would have written long before this. I have been on the point of dropping him a line at least a dozen times during the past six weeks, but I always decided to wait a day or two longer, and see if we shouldn't hear from him. But now I will write." And so I did. I directed the letter to Paris, and thought, "Now we shall hear from him before this letter is fifty miles from Heidelberg—it always happens so."

True enough; but why should it? That is the puzzling part of it. We are always talking about letters "crossing" each other, for that is one of the very commonest accidents of this life. We call it "accident," but perhaps we misname it. We have the instinct a dozen times a year that the letter we are writing is going to "cross" the other person's letter; and if the reader will rack his memory a little he will recall the fact that this presentiment had strength enough to it to make him cut his letter down to a decided briefness, because it would be a waste of time to write a letter which was going to "cross," and hence be a useless letter. I think that in my experience this instinct has generally come to me in cases where I had put off my letter a good while in the hope that the other person would write.

Yes, as I was saying, I had waited five or six weeks; then I wrote but three lines, because I felt and seemed to know that a letter from Millet would cross mine. And so it did. He wrote the same day that I wrote. The letters crossed each other. His letter went to Berlin, care of the American minister, who sent it to me. In this letter Millet said he had been trying for six weeks to stumble upon somebody who knew my German address, and at last the idea had occurred to him that a letter sent to the care of the embassy at Berlin might possibly find me. Maybe it was an "accident" that he finally determined to write me at the same moment that I finally determined to write him, but I think not.

With me the most irritating thing has been to wait a tedious time in a purely business matter, hoping that the other party will do the writing, and then sit down and do it myself, perfectly satisfied that that other man is sitting down at the same moment to write a letter which will "cross" mine. And yet one must go on writing, just the same; because if you get up from your table and postpone, that other man will do the same thing, exactly as if you two were harnessed together like the Siamese twins, and must duplicate each other's movements.

Several months before I left home a New York firm did some work about the house for me, and did not make a success of it, as it seemed to me. When the bill came, I wrote and said I wanted the work perfected before I paid. They replied that they were very busy, but that as soon as they could spare the proper man the thing should be done. I waited more than two months, enduring as patiently as possible the companionship of doorbells which would fire away of their own accord sometimes when nobody was touching them, and at other times wouldn't ring though you struck the button with a sledge-hammer. Many a time I got ready to write and then postponed it; but at last I sat down one evening and poured out my grief to the extent of a page or so, and then cut my letter suddenly short, because a strong instinct told me that the firm had begun to move in the matter. When I came down to breakfast next morning the postman had not yet taken my letter away, but the electrical man had been there, done his work, and was gone again! He had received his orders the previous evening from his employers, and had come up by the night train.

If that was an "accident," it took about three months to get it up in good shape.

One evening last summer I arrived in Washington, registered at the Arlington Hotel, and went to my room. I read and smoked until ten o'clock; then, finding I was not yet sleepy, I thought I would take a breath of fresh air. So I went forth in the rain, and tramped through one street after another in an aimless and enjoyable way. I knew that Mr. O______—, a friend of mine, was in town, and I wished I might run across him; but I did not propose to hunt for him at midnight, especially as I did not know where he was stopping. Toward twelve o'clock the streets had become so deserted that I felt lonesome; so I stepped into a cigar shop far up the avenue, and remained there fifteen minutes, listening to some bummers discussing national politics. Suddenly the spirit of prophecy came upon me, and I said to myself, "Now I will go out at this door, turn to the left, walk ten steps, and meet Mr. O______ face to face." I did it, too! All right, I could not see his face, because he had an umbrella before it, and it was pretty dark anyhow; but he interrupted the man he was walking and talking with, and I recognized his voice and stopped him.

That I should step out there and stumble upon Mr. O______ was nothing, but that I should know beforehand that I was going to do it was a good deal. It is a very curious thing when you come to look at it. I stood far within the cigar shop when I delivered my prophecy; I walked about five steps to the door, opened it, closed it after me, walked down a flight of three steps to the sidewalk, then turned to the left and walked four or five more, and found my man. I repeat that in itself the thing was nothing; but to know it would happen so beforehand, wasn't that really curious?

I have criticized absent people so often, and then discovered, to my humiliation, that I was talking with their relatives, that I have grown superstitious about that sort of thing and dropped it. How like an idiot one feels after a blunder like that!

We are always mentioning people, and in that very instant they appear before us. We laugh, and say, "Speak of the devil," and so forth, and there we drop it, considering it an "accident." It is a cheap and convenient way of disposing of a grave and very puzzling mystery. The fact is, it does seem to happen too often to be an accident.

Now I come to the oddest thing that ever happened to me. Two or three years ago I was lying in bed, idly musing, one morning—it was the 2nd of March—when suddenly a red-hot new idea came whistling down into my camp, and exploded with such comprehensive effectiveness as to sweep the vicinity clean of rubbishy reflections and fill the air with their dust and flying fragments. This idea, stated in simple phrase, was that the time was ripe and the market ready for a certain book; a book which ought to be written at once; a book which must command attention and be of peculiar interest—to wit, a book about the Nevada silver-mines. The "Great Bonanza" was a new wonder then, and everybody was talking about it. It seemed to me that the person best qualified to write this book was Mr. William H. Wright, a journalist of Virginia, Nevada, by whose side I had scribbled many months when I was a reporter there ten or twelve years before. He might be alive still; he might be dead; I could not tell; but I would write him, anyway. I began by merely and modestly suggesting that he make such a book; but my interest grew as I went on, and I ventured to map out what I thought ought to be the plan of the work, he being an old friend, and not given to taking good intentions for ill. I even dealt with details, and suggested the order and sequence which they should follow. I was about to put the manuscript in an envelope, when the thought occurred to me that if this book should be written at my suggestion, and then no publisher happened to want it, I should feel uncomfortable; so I concluded to keep my letter back until I should have secured a publisher. I pigeonholed my document, and dropped a note to my own publisher, asking him to name a day for a business consultation. He was out of town on a far journey.

My note remained unanswered, and at the end of three or four days the whole matter had passed out of my mind. On the 9th of March the postman brought three or four letters, and among them a thick one whose superscription was in a hand which seemed dimly familiar to me. I could not "place" it at first, but presently I succeeded. Then I said to a visiting relative who was present:

"Now I will do a miracle. I will tell you everything this letter contains—date, signature, and all—without breaking the seal. It is from a Mr. Wright, of Virginia, Nevada, and is dated the 2nd of March—seven days ago. Mr. Wright proposes to make a book about the silver-mines and the Great Bonanza, and asks what I, as a friend, think of the idea. He says his subjects are to be so and so, their order and sequence so and so, and he will close with a history of the chief feature of the book, the Great Bonanza."

I opened the letter, and showed that I had stated the date and the contents correctly. Mr. Wright's letter simply contained what my own letter, written on the same date, contained, and mine still lay in its pigeonhole, where it had been lying during the seven days since it was written.

There was no clairvoyance about this, if I rightly comprehend what clairvoyance is. I think the clairvoyant professes to actually see concealed writing, and read it off word for word. This was not my case. I only seemed to know, and to know absolutely, the contents of the letter in detail and due order, but I had to word them myself. I translated them, so to speak, out of Wright's language into my own.

Wright's letter and the one which I had written to him but never sent were in substance the same.

Necessarily this could not come by accident; such elaborate accidents

cannot happen. Chance might have duplicated one or two of the details, but she

would have broken down on the rest. I could not doubt—there was no tenable

reason for doubting—that Mr. Wright's mind and mine had been in close and

crystal-clear communication with each other across three thousand miles of

mountain and desert on the morning of the 2d of March. I did not consider that

both minds originated that succession of ideas, but that one mind originated it,

and simply telegraphed it to the other. I was curious to know which brain was

the telegrapher and which the receiver, so I wrote and asked for particulars.

Mr. Wright's reply showed that his mind had done the originating and

telegraphing, and mine the receiving. Mark that significant thing now; consider

for a moment how many a splendid "original" idea has been unconsciously stolen

from a man three thousand miles away! If one should question that this is so,

let him look into the encyclopedia and note once more that curious thing in the

history of inventions which has puzzled everyone so much—that is, the frequency

with which the same machine or other contrivance has been invented at the same

time by several persons in different quarters of the globe.

The world was without an electric telegraph

for several thousand years; then Professor Henry, the American, Wheatstone in

England, Morse on the sea, and a German in Munich, all invented it at the same

time. The discovery of certain ways of applying steam was made in two or three

countries in the same year. Is it not possible that inventors are constantly and

unwittingly stealing each other's ideas whilst they stand thousands of miles

asunder?

The world was without an electric telegraph

for several thousand years; then Professor Henry, the American, Wheatstone in

England, Morse on the sea, and a German in Munich, all invented it at the same

time. The discovery of certain ways of applying steam was made in two or three

countries in the same year. Is it not possible that inventors are constantly and

unwittingly stealing each other's ideas whilst they stand thousands of miles

asunder?

Last spring a literary friend of mine, W. D. Howells, who lived a hundred miles away, paid me a visit; and in the course of our talk he said he had made discovery—conceived an entirely new idea—one which certainly had never been used in literature. He told me what it was. I handed him a manuscript, and said he would find substantially the same idea in that—a manuscript which I had written a week before. The idea had been in my mind since the previous November; it had only entered his while I was putting it on paper, a week gone by. He had not yet written his; so he left it unwritten, and gracefully made over all his right and title in the idea to me.

The following statement, which I have clipped from a newspaper, is true. I had the facts from Mr. Howells' lips when the episode was new:

A remarkable story of a literary coincidence is told of Mr. Howells' Atlantic Monthly serial, "Dr. Breen's Practice." A lady of Rochester, New York, contributed to the magazine after "Dr. Breen's Practice" was in type, a short story which so much resembled Mr. Howells' that he felt it necessary to call upon her and explain the situation of affairs in order that no charge of plagiarism might be preferred against him. He showed her the proof-sheets of his story, and satisfied her that the similarity between her work and his was one of those strange coincidences which have from time to time occurred in the literary world.

I, personally, had read portions of Mr. Howells' story, both in manuscript and in proof, before the lady offered her contribution to the magazine.

Here is another case. I clip it from a newspaper:

The republication of Miss Alcott's novel Moods recalls to a writer in the Boston Post a singular coincidence which was brought to light before the book was first published: "Miss Anna M. Crane, of Baltimore, published Emily Chester, a novel which was pronounced a very striking and strong story. A comparison of this book with Moods showed that the two writers, though entire strangers to each other, and living hundreds of miles apart, had both chosen the same subject for their novels, had followed almost the same line of treatment up to a certain point, where the parallel ceased, and the denouements were entirely opposite. And even more curious, the leading characters in both books had identically the same names, so that the names in Miss Alcott's novel had to be changed. Then the book was published by Loring."

Four or five times within my recollection there has been a lively newspaper war in this country over poems whose authorship was claimed by two or three different people at the same time. There was a war of this kind over "Nothing to Wear," "Beautiful Snow," "Rock me to Sleep, Mother," and also over one of Mr. Will Carleton's early ballads, I think. These were all blameless cases of unintentional and unwitting mental telegraphy, I judge.

A word more as to Mr. Wright. He had had his book in mind some time; consequently he, and not I, had originated the idea of it. The subject was entirely foreign to my thoughts; I was wholly absorbed in other things. Yet this friend, whom I had not seen and had hardly thought of for eleven years, was able to shoot his thoughts at me across three thousand miles of country, and fill my head with them, to the exclusion of every other interest, in a single moment. He had begun his letter after finishing his work on the morning paper—a little after three o'clock, he said. When it was three in the morning in Nevada it was about six in Hartford, where I lay awake thinking about nothing in particular; and just about that time his ideas came pouring into my head from across the continent, and I got up and put them on paper, under the impression that they were my own original thoughts.

I have never seen any mesmeric or clairvoyant performances or spiritual manifestations which were in the least degree convincing—a fact which is not of consequence, since my opportunities have been meager; but I am forced to believe that one human mind (still inhabiting the flesh) can communicate with another, over any sort of a distance, and without any artificial preparation of "sympathetic conditions" to act as a transmitting agent. I suppose that when the sympathetic conditions happen to exist the two minds communicate with each other, and that otherwise they don't; and I suppose that if the sympathetic conditions could be kept up right along, the two minds would continue to correspond without limit as to time.

Now there is that curious thing which happens to everybody: suddenly a succession of thoughts or sensations flocks in upon you, which startles you with the weird idea that you have ages ago experienced just this succession of thoughts or sensations in a previous existence. (The phenomenon we now call "Déjà vu". —Paul) The previous existence is possible, no doubt; but I am persuaded that the solution of this hoary mystery lies not there, but in the fact that some far-off stranger has been telegraphing his thoughts and sensations into your consciousness, and that he stopped because some counter-current or other obstruction intruded and broke the line of communication. Perhaps they seem repetitions to you because they are repetitions, got at second hand from the other man. Possibly Mr. Brown, the "mind-reader," reads other people's minds, possibly he does not; but I know of a surety that I have read another man's mind, and therefore I do not see why Mr. Brown shouldn't do the like also.

Mental Telegraphy Part 2

| By: Mark Twain | Posted: 2/22/2007 |

Page Views: 4686 | |

| Topics: #Spirituality #Science #Metaphysics #MarkTwain #Synchronicity #Telepathy | |||

| The continuation of Mark Twain's writings on 'Mental Telegraphy'. | |||

Clemens talks about "accidents"—what we, today, call coincidences or synchronicity. The science of statistics wasn't well-established in Clemens' day, but today's statisticians try to tell us that "coincidences" are meaningless; that they are the result of the patterning human mind imposing seeming order on what is actually random chance.

Read more…

Mental Telegraphy Part 3

| By: Mark Twain | Posted: 2/23/2007 |

Page Views: 4329 | |

| Topics: #Spirituality #Metaphysics #MarkTwain #Synchronicity #Telepathy | |||

| The conclusion of Mark Twain's essays on telepathy. | |||

At the end of yesterday's guest blog, Sam Clemens described an odd circumstance which, while not exactly an example of his "mental telegraphy," nevertheless qualified as what we, today, would call "high strangeness." As he watched a stranger approach his house, the stranger seemed to disappear. When Clemens found the stranger had, in fact, rung and been admitted through the front door, he concluded that he must have unknowingly fallen asleep, or unconscious, for the sixty seconds (minimum) that it took the visitor to walk past him, ring the doorbell and be admitted.

Read more…