| By: Agnes Steinberg | Viewed: 4/19/2024 |

Page Views: 7516 | |

| Topics: #AgnesSteinberg #Yorkers #NewYork | |||

| Memoirs of my dead ex-mother-in-law's childhood in turn-of-the-century Yonkers, New York. | |||

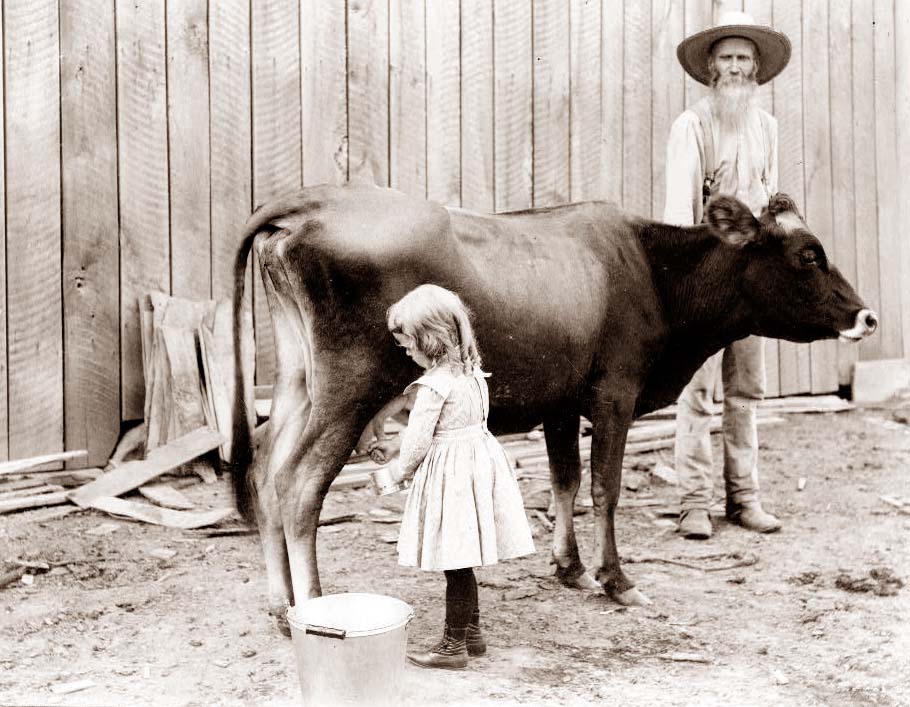

Agnes with my two oldest daughters, Dorothy and Karen.

Forward

Half-hidden in these purple shadows runs a narrow path. Few know that it exists. Stoop low and follow as it twists and winds and leads us on. Here is a spot where fact and fancy mingle. To linger is not safe. Shall we turn back? Too late! The way is already blocked. Perhaps this pointing sign may lead us out. Its blurred letters read, "To Days Gone By."

The Time, The Place

I was not a child prodigy, lived in no remote or exotic place, shared no amazing experiences. Why, then, bother to record the following?

It happened this way. The other day, business took me to the old neighborhood where I had lived. I explored the few blocks, standing stock still now and then, half hoping that out of the familiar haunts would emerge the forms of loved long-departed or childhood playmates who would remember, too. I noted what remained the same, recalled what had gone, sensed the past activities as truly as the walls of a house absorb the daily atmosphere of the life being lived within it. I walked on.

That night, unable to sleep, my mind kept adding a detail here, a scene there until the whole, like a play being enacted upon a stage before me, was vivid, complete, again alive. With a shock, I realized that, although not many years had slowly turned since we had moved away, time had worked so relentlessly that the environment, the interests, even most of the physical setting were now as much a part of by-gone days as the flowers of the Bouwerie or horse-car travel.

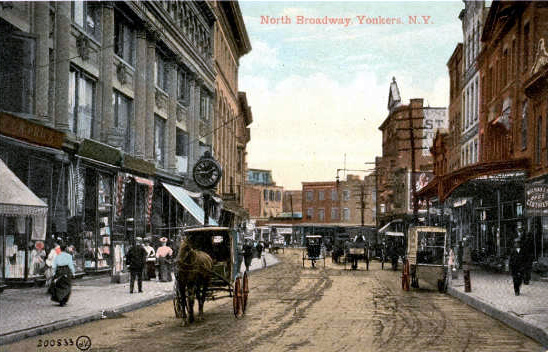

The era in question was somewhere around 1909, the neighborhood, genteel, quiet, middle-class. The street, between Lexington and Third Avenues in the East, was lined entirely with old, high-stooped brownstone private houses and a few new flat-fronted white stone ones.

On three of the corners were red brick apartment houses with brown trim, four stories high—each entire floor being an apartment. In one of the latter on the Northeast corner of Third Avenue, I spent eight or ten years of that blissful period of life in which there is no yesterday and no tomorrow.

No consciousness of the problems or trials which await, shadow the brightness of the current day. Like believing in Santa Claus, the fragile, fairy tale state is as real as earth or sky (though the scientist in us can lay no finger upon its fragile existence) and, like Humpty-Dumpty, once it has passed and been broken, "not all the King's horses and all the King's men" can put it together again.

The Exterior

Three windows of the long, second-floor apartment faced east; seven faced south, and the last room, the kitchen, faced south on East 34th Street, west towards the Park and north over a flagstoned back yard almost as large as the house itself. This yard was entered from the street by a huge, solid black door in a curving brick wall. Entering it always involved some risk or uncertainty as one never knew what was to be found on the other side.

Sometimes, it was a clothes-line man, climbing the high, thick pole to put up a line for an arriving tenant or to remove one for a family going away. Or a band of German musicians might stand playing precise, martial music or Viennese waltzes upon highly polished brass instruments. Sometimes a blind man gently fingered an old violin, or a couple sang a duet. On rare occasions, a voice of unusual beauty would rise quivering above the clothes-lines and pass searching through the open windows to tug at the heart strings of the housewife while she peeled her potatoes. Then, up on the shelf, the pewter mug would be opened, a penny or two taken out, wrapped in a scrap of paper, and flung to the entertainer below.

Occasionally, a suspicious-looking stranger loitered aimlessly there or in the next yard, separated from ours by another wall and entered by a small door. No! Back yards were definitely not regions to be explored when alone. Even when in groups, we entered timidly.

Access to the house itself was through a wrought-iron fencing about three feet high which guarded each side of the doorway. A pair of solid, high wooden doors opened wide in the daytime, and closed and locked after 10 p.m., led into a small vestibule at street level. Halfway up on the left wall were three letter boxes, each one surmounted by a mouthpiece sunken into the wall and having beneath it a lever. When pulled down, this lever started a bell jangling in the kitchen in an apartment above. Also in the kitchen was a corresponding lever which, when operated, wreaked havoc with a chain on the inside of the inner, frosted-glass doors of the vestibule. This clanking procedure wrestled with the door lock and finally admitted the entering presence.

Mischief

In moments of idleness, we used to lie in wait inside for an unsuspecting visitor. When one came along and rang the bell, we stealthily disconnected one of the links of the opening chain so that admission was impossible. On the second and third attempt the bell was rung more emphatically by the impatient guest. Always the answering but futile jangling of the chain followed. By this time the infuriated visitor would dash out into the street and look up at the windows of the apartment to be visited, seeking an explanation. The expectant host, hanging halfway out the window, would wrathfully inquire what under the sun was the matter with him, that he didn't open the door and walk up. At that precise moment, we quickly connected the chain again and innocently sauntered into the street, whereupon the visitor, seeing the slowly closing door, made a dash to get through it and up the stairs. Needless to say, it was unwise to attempt a repeat performance with the same guest upon any of his future visits.

Two long flights of carpeted stairs brought him to the second floor. Here a choice of four entrances, all leading to the same apartment, presented itself. The first door belonged to a hall bedroom; the second led to the parlor; the third, to a sitting room; and the fourth, to another hall bedroom. Before heading for any of these, he usually waited until the unbolting of a lock and a ray of light indicated by which one he was to enter. the selection of the door to be opened marked his status as irrevocably as the caste system of the East.

Important persons, business connections, little-known guests and those upon whom an impression was to be made were ushered into the parlor and left to sit in cool silence while the proper member of the household was summoned. Doctors, clergymen and others on official sick calls were conducted personally through the hall bedroom portals with softly murmured pleasantries. Members of the family, relatives and close friends were greeted by a kiss and a hug or a wave of the hand, and allowed to follow at will through the dining room door left wide for their convenience. Well, indeed, might they smile with satisfaction who had been assigned to the last-mentioned entrance, secure in the knowledge that they bore the stamp of approval and really "belonged."

The Interior

On the inside, the rooms and furnishings were probably typical of any similar home of that time—with two exceptions. I know the dining room was unique; I like to think the kitchen was, too.

Here I shall have to inject a brief explanation as to why the dinning room was used for dining on Sundays only. My father having died when I was eighteen months old, my mother, heartbroken and scarcely caring whether or not she lived from day to day, returned with me to her mother's home. There we were welcomed with open arms by my grandmother and two maiden aunts. When I was six, one of the aunts entered a cloistered convent and vanished forever from our family circle, but never from our hearts, thus leaving a family consisting of Grandma, Mother and Aunt Mary. The latter was the real businessman and breadwinner, Mother assisting with shopping and Grandma keeping house and cooking.

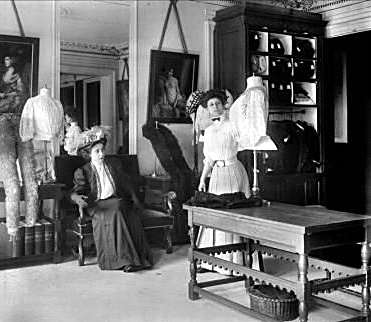

Our means were limited, indeed. Aunt Mary was an excellent

dressmaker and had a number of good, steady, well-to-do customers

most of whom were driven up to our door in their own coaches. But

the orders were spasmodic; now plentiful, now scarce. The dining

room was, of necessity, the work room. No carpet could be spread

upon the floor. Two long, bare tables, with drawers for scissors,

pincushions and tape measures were the chief pieces of furniture. A

dressmaker's form, adjustable to the size of thin or stout ladies,

decorated one corner and an old Wilcox and Gibbs sewing machine

stood by the window. A fireplace with black marble mantel between

the two windows and a curtained dish closet reaching from ceiling to

floor completed the decor. Here the breadwinning took place from

daylight till six or later at night. Around the tables sat the girls

who were employed, their number indicating the prosperity or

slackness of the season. In the evening the instruments of trade

were put away, the floor swept clean of pins, scraps and threads. A

white sheet was thrown over a line strung catty-corner from wall to

wall, upon which hung the current and always fine products of a

creative mind and patient fingers.

decorated one corner and an old Wilcox and Gibbs sewing machine

stood by the window. A fireplace with black marble mantel between

the two windows and a curtained dish closet reaching from ceiling to

floor completed the decor. Here the breadwinning took place from

daylight till six or later at night. Around the tables sat the girls

who were employed, their number indicating the prosperity or

slackness of the season. In the evening the instruments of trade

were put away, the floor swept clean of pins, scraps and threads. A

white sheet was thrown over a line strung catty-corner from wall to

wall, upon which hung the current and always fine products of a

creative mind and patient fingers.

But, Saturday night wrought transformation! Sweeping, scrubbing and dusting removed every sign of dirt and work. The machine was closed. A large fine damask cloth and matching napkins covered the two tables now pushed together in the room. The best dishes and platter emerged from their hiding place in the closet; a glass bowl of fruit appeared in the center of the table. Chairs were placed around and places set with cups and dishes turned face down. The week was ended with finality, kept as a day apart. In the cycle of the days of the week, it stood out as the jewel in the circle of a ring.

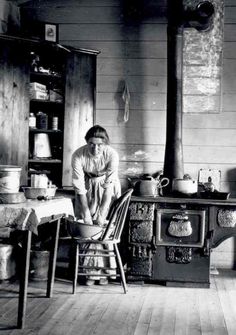

The kitchen was the favorite spot. A square, cheerful room, not too large considering its many uses, it was sunny in winter and cool in summer because of the awnings, three-way exposure and tall trees towering outside close to the walls. There were the usual sink and covered washtubs of the period, long dish closet, high narrow window with pasted, paper lattice in black and red diamond-shaped design, a table at which the family ate meals on week-days, two larger windows with deep inside windowsills. On the latter, the cat slept among geraniums in winter and pansy pots in summer, and I curled up and read for hours on many a rainy day. The charm of the kitchen was its simplicity. It contained no unnecessary items. Yet, as functional as its predecessor, the one-room cabin of the pioneer, it satisfied completely all fundamental needs.

How many starched petticoats, dimity dresses and broad blue or pink satin sashes were ironed in this room? How many family washes rose cleansed and steaming from the tub? How often Grandma sat with a wooden bowl upon her lap and chopped giblets or hash! Here she dozed rocking slowly back and forth by the hearth, as all old folks should doze for a little while each day. Here molasses taffy, sharpened by a drop of vinegar and a pat of butter, was spun on winter afternoons. Here corn was popped in the fall. No wonder that I loved the kitchen. For me its activity was unhurried and unplanned.

Within it also was to be found a corner unlike any other in the houses of friends or relatives. A low, small coal stove, squatting flat, evidently replaced an open hearth for the latter protruded beneath it, and the red brick fireplace still stood, framing the stove on top and sides. Saturday brought rejuvenation to the stove, also, its lids becoming satiny black and its handles bright. Lifter and pot holders and a set of irons standing on end reposed on the mantel, flanked by a pair of beer steins. Coal scuttle and shovel and round bundles of wooden blocks stood ready at the side.

Today, we switch on and off the controls of radio, refrigerator or car with thoughtless ease and instant result. Gone is the personal touch that tempered the heat of the iron or scrubbed spot. How many today could compete with the sure, swift, simple skill that built the fire, turned dampers to send flames roaring up the chimney or banked the red embers to hold a cozy warmth for a long winter night?

Last of all, standing aloof and watchful in its corner, was that lifeline of earlier days, the dumbwaiter. A shrill blast of the whistle announced that something awaited below. The door was opened. A loud "YES?" was sent down into the dark depths and a feeble answering reply returned. Perhaps Tony the ice-man was raising a block of ice, or a three-foot bag of coal was rising with its accompanying bundle of wood. Perhaps, protruding from a basket, tonight's dinner was arriving; or the news of the universe, via the Pulitzer World, clamored for admission. Change making was also carried on. A dollar bill fastened down with a large bit of coal descended in payment. In due time, three cents arose. What a versatile gadget it was!

A very exciting process, but one frowned upon by elders, was to open the door a few inches to note, as the laden conveyance slowly passed, what Mrs. B. on the floor above would be feeding her family.

The descent was, if possible, of even greater interest. About five o'clock in the afternoon blasts were heard in each kitchen, indicating that the janitor below was ready to collect and remove refuse. The empty dumbwaiter, light in weight, with ropes slapping the sides of the shaft, swiftly rose to the top floor. The family there deposited its garbage can and bundles of sweepings and papers on the top shelf. It slowly descended to our level. We likewise filled the second shelf, while a discerning eye couldn't help noting that at last Mrs. B. was discarding the hat with the pink feather, that Jane had broken her doll beyond repair or that the crash earlier that afternoon must have been the brown crockery tea pot now reposing in fragments before us.

Nor was the procedure without its moments of pathos. I remember standing rigid while I watched the small white form of my kitten spread limp and lifeless on the shelf, start on its last journey. It had been my pet for just three weeks, yet part of my heart descended into the black depths with it, as I stood licking the salt tears that rolled down my cheeks.

Each To His Own

Within the home lived three very different persons.

My grandmother, short and plump, even of disposition and tolerant of nonsense, was our ally and conspirator at times. The sharp emotions of so many years had left her a stability which nothing seemed to move too deeply any more. With easy grace she finished each culinary chore in her domain—the kitchen.

Sometimes of an evening, having had more than my fair share during the day, I would help myself to more of the chocolate peppermints which some thoughtful guest had brought and which were kept in Grandmother's neatly arranged bureau drawer.

If the pilferage were soon discovered, I dropped to my knees at the bedside as if for evening prayer, peeking out from behind clasped fingers at the progress of the chase and secure in the knowledge that my devout grandmother wouldn't disturb the child while she was "talking to God". In this way the moment of retribution was postponed and the incident always purposely forgotten by the time my "prayers" were finished.

Rain drops drumming on the window never failed to summon her to cross the sea in spirit and to stand again, a gray-eyed lass beside the Shannon or to walk the Limerick road. The present slipped away. In song and verse she had learned long ago and now repeated letter-perfect and always fraught with longing, I met her fisher folk, I listened to the winds that moved the boats or watched the mounting clouds, the flight of birds that tell of the storm. In dark and misty bogs, the Faerie lights of Ireland would begin to twinkle while eerie leprechauns were busy at their pranks…

But should a sudden rainbow flood the sky with green and red, we would hurry back again, my grandmother and I, the visit still unfinished, to await the story-telling hour of another rainy day.

The business aspects of the home were precisely managed by Aunt Mary. Taller than the rest of us, thin and always delicate of constitution, she never spared herself. The fingers of her hands were knotted with unceasing toil. Spare of word and keen of judgment, in her nature early hardships had left their mark, and much of Puritan severity remained. All things were measured by the yardstick of their eternal values.

No time was wasted in idle gossip or in visiting. Yet she was hospitality itself when company came. She made things pleasant, often giving up her own bed that they might stop overnight and doing, herself, much of the "fancy" cooking for the guests. Aunt Mary might tell you bluntly that the question to which you sought an answer was not your affair, but there would be no dealing in evasion or "white lies". Her word was her bond. With the landlord, her spoken agreement held more weight than the signed lease of our neighbor. A shipment of fine-quality yard goods might arrive solely in response to a verbal request. Mrs. T's dress promised for Tuesday, would be delivered on that day, through its completion required an all-night sewing session.

As I grew, great admiration developed within me for my aunt. I found the strict adherence to the letter of the law was chiefly for herself. An overwhelming kindliness for others evened up score.

To me, no word of praise was ever given, lest I grow conceited. Yet, she would shield me from all things that were a hardship to her, as a child. An unexpected bag of candy appeared when funds were low. A new school coat was bought, when season after season she had been wearing down the cuffs and elbows of her own. Here was a gift, hand-made while orders waited, if one could not be bought, that I might be present at someone's birthday party. A bunch of pink sweet peas might blossom on a winter morning for a little girl in bed with tonsillitis. So many different things revealed the deep devotion of which, like any true New England daughter, no one ever heard her speak.

A whiff of drifting perfume, gay laughter, brown eyes beneath a veil, a feminine gesture, violets and fur waiting on the table—my Mother had passed by; and, trailing her, a cluster of admiring glances. All things frivolous and social came her way. She loved them. Visits to relatives, plays at school, friends in to supper on a Sunday night—these were no small part of my mother's life. And beaus came, too, to play cribbage or to take us for a carriage ride. They came, but just so far—no further. The gay exterior was but the armor of a promised heart.

Have you ever seen a woman walking through a dark and empty hallway, carrying a candle, its sputtering flame protected by her hand? Just so I've seen my Mother walking down the years—the stealthy years that slowly make so many subtle changes. In time, her quick light step grows slow and falters. Brown hair turns to gray and then to white. Shoulders straight and strong grow frail and rounded. The gay, high voice is low and very seldom heard.

Yet there are things that never, never change. For to me it always seems as though she carries the candle high, the shining symbol of unwavering love. The lips are ever uncomplaining. The mind knows what it seeks. The eyes are steady, looking forward into darkness, but darkness broken by the rays her candle sheds. Beyond, my mother feels, a heart is waiting, and a hand she lost to clasp her own once more. The steadfast flame, so carefully guarded through a lifetime, reveals the lovers to each other at life's end.

Romance

A broadening and interesting factor was contact with the "customers"—those ladies of upper middle class gentility who came, sometimes by trolley or "el", sometimes in their own small carriages seeking the skill of Aunt Mary in making or remodeling dresses.

The fittings took place in the parlor. Thither my aunt would hasten, bearing pinned to her bosom a pincushion studded with pins and needles, and carrying over her arm lovely rustling taffetas or organdies, rich broadcloths, or velvets.

The fitting over, and the important lady standing before the mirror puncturing her feathered hat with hat pins of great length, an invitation was often forthcoming for the child of the family to "come in". As in all circles of life, the clientele was composed of very different personalities. With some, I was shy; with others, friendly. Some could not entice me into the room upon the second visit or thereafter.

Among the most faithful of customers were the wife of a prominent surgeon, her two grown daughters and her mother. Mrs. D. requested that a long pocket be put into the folds of all her skirts, as a convenient place for carrying small change, etc. Into this mysterious hiding place I was always invited to thrust my hand. Sometimes it would contain a pretty carved figurine from China (the two daughters had been missionary workers in the Orient); sometimes, a pair of silver buttons, a tiny doll, or a fancy pencil. The uncertain nature of the gift held fascination. Could it be this same expectant urge which pilots me today to auctions and antique shops?

The greatest thrill of the dressmaking business, however, was provided by the brides. Oh, the beautiful, beautiful brides! Every once in a while the daughter of one of the patronesses would promise her hand to a suitor. Or perhaps it would be the lady herself, a widow striving to replace in a second marriage a lost love, or a spinster coming perilously close to the brink of abandoned expectations who would present herself to be arrayed as the chosen one.

On the occasion of such a fitting, white sheets were spread over the parlor carpet in advance; the shades outside the curtains drawn down to the windowsills, the latticed blinds closed on the shades, thus excluding all possible daylight. Then at the touch of the gas lighter equipped with a sliding wax taper, each of the four frosted glass globes branching off from the center pipe burst into a mellow glow, giving somewhat the effect of candlelight.

The stage was now set; the ring of the doorbell awaited. Farther back in the dining room, I crouched in hopeful suspense. Would I be asked to "come in" today? Oh, voluminous folds of lush satin! Oh, crispness of net and lace! Oh, delicate scent of sachet, as the white-sheeted bridal outfit was whisked away through the door and disappeared into the parlor.

Pinning and snipping and fitting completed to satisfaction, I was summoned into the presence, invited to view the vision.

And a vision indeed she always was, with a flush on her cheeks, a light in her eyes, as she turned and swayed, looking over her shoulder to see the great mirror, a long swirling train, graceful narrow sleeves, the soft glow of seed pearls, the shimmer of satin.

The bride-to-be was pleased! She was joyful! Then, glancing at me, she sought confirmation. What greater proof could she ask than the speechless adoration seen in a child's wide eyes? Truly her hour of fulfillment was at hand. The white glory of the bride without, but faintly echoed the radiance within.

Business of the Day

On those delightful occasions when school was not in session, the day officially began when, breakfast over, and dressed in suitable seasonal attire, the younger generation arrived upon the street. "Equipment" which varied from day to day was carried—usually an old thread or candy box. Today, it might contain a set of jacks and ball; tomorrow, a small china doll with bits of lace, material and thread for making costumes. another day might call for a stamped table doily and strands of different-colored embroidery floss. One good look up and down the street sufficed to settle the question of who was out, who still had to be called for, what was going on and the best means of getting the situation in hand. If ever a street was played upon from dawn till dark, it was that one long block between Lexington and Third.

Besides the five families who possessed offspring and whom we descended upon in droves from time to time, we children had a speaking acquaintance with not one household. In fact, I do not remember ever having seen a single person go into or out of any other house. Did their owners stand behind the long lace curtains of the parlors and watch our antics with amusement or perhaps resignation? Or were they so preoccupied as to be unconscious of our existence? Whatever the answer, to their credit be it said that very, very seldom was a butler or maid dispatched to curb our activities. And they endured much.

In groups we sat upon their lower steps for hours. When the summer sun burned, we retreated up the stoop and entrenched ourselves beneath their front door awnings. Area gates were mounted and swung upon. Across their sidewalks in winter were formed sliding ponds of thinly-fallen slow. Icy igloos and forts were built before their coal holes. Heavy solid marbles, the size of a plum, were bounced hundreds of times without a miss upon the flagstones—often glancing off up into the air and teetering dangerously near the area windows. The center of the street and sidewalks were covered with great chalk "potsie" circles in which we jumped through the spider web from "start" to "home". Lines formed to wait a turn at jump rope. When hide-and-seek was in vogue we hid behind their outer opened doors. Yet the greatest trial of all must have been to watch and listen as whole armies of shouting roller skaters flew up and down the sidewalks or skated clockwise on the wide spots.

Whatever their destination in another world, may tranquility descend upon them as, in bygone days these long-suffering proprietors granted us our unmolested freedom.

We played with gusto and a directness that would have confounded the theories of many a philosopher. If a game was good, we repeated it again and again till we were exhausted; if we didn't like it, it was taboo. All, without exception, turned their attention to the same recreation at the same time, as though a gong had been sounded for the ending of one sport and the beginning of another.

With the exception of a few rousing games of "Cops and Robbers" or a few good snowball fights, the boys kept pretty much to themselves. A girl was considered a tom-boy if she had much to do with them.

A most peculiar feature of those years was being "best friends". The basis upon which the selection was made is hidden in history. If you decided to be "best friends" with Mary, from that moment forward, you were her partner in all games, her second in arguments; you shared her secrets, candy, and skate key. In other words you became each other's shadow. The system had many advantages, not the least of which was moral support in a crisis. The alliance might last for ten minutes, for a day, or for years. Either party could terminate it at will with the brief and blunt statement that she no longer wanted to be the other's best friend. Yet, while it existed, no documented and signed contract between individuals or nations was ever maintained with greater fidelity.

Like No Other

When weather cleared the street of the noisy flock, novel local spots were to be visited. The bakery around the corner, owned by Helen's father, claimed first attention. There behind windows frosted with steam, Mr. G. presided over shelves of tempting pastries. Small, ruddy-cheeked, dark-eyed and sound as an apple, his good business management always succeeded in making a very fine living. Mrs. G., blond and gentle, arrayed in a long white apron like her husband, assisted behind the counter as did the older sister and brother—although the latter could most often be found rising from the basement stairs to the sidewalk like a white apparition, carrying high above his head immense tin trays laden with cakes fresh from the oven.

As Helen's "best friend", I was granted carte blanche to the premises. We roamed through the family's apartment above, looked in on the goodies cooking in the kitchen pots, had kaffee klatch or supper at the back tables of the store and, occasionally, were even permitted a trip through that mysterious region: the basement. Here, beneath the sidewalk, squads of bakers working day and night took care of all those amazing processes which resulted in the masterpieces displayed on counters above. It was a privilege allowed to no others, to roam below unsupervised and tantalized by the odors of fresh dough, of dried apples, cherries, citron, raisins and nuts, and snatching a morsel here and there as we passed.

No more generous family ever lived. A dozen rolls always numbered thirteen. One day a pair of fine ball-bearing skates arrived for Helen, and a second pair for me. Weekly, the square, black carriage of the Little Sisters of the Poor pulled up before the entrance. A huge empty clothes basket entered the store and in a few minutes emerged creaking under its weight of food donated. The blessings of the departing Sisters must have lingered for this family prospered. "Bread cast upon the waters" seemed to return with the success of every new store opened.

Not far away, the pungent odors of tobacco circled. Two of our playmates, noses pressed flat against the rain-spattered door of their father's cigar store, gazed out past the painted wooden Indian posing erect and virile in the torrents. Entering, we stopped to chat, unimpressed by case after case of gold-banded cigars. In the rear behind a curtain, a half-dozen workers stooped over tables laden with brown, dry leaves. The rolling, shaping, clipping, and boxing of cigars went on hour after hour with monotonous precision. No color, no prettiness, no pleasing flavor arose to greet our appraising senses. A visit here might help to kill time on a dull day, but one or two such would suffice for the year.

Wind and rain tearing around the corner assisted our flight halfway up the block. A white stone building boasting of two entrances gave greater promise and here a halt was called.

Hopefully we rang the bell. Perhaps the horses would be out! "The horses?" a stranger, startled, might have enquired. "Out?" Yes. This was the carriage house where dwelt others of our tribe.

Mr. F., thin and wiry, Mrs. F., plump and patient in spite of the brood clinging to her skirts and the baby carriage always standing in anticipation of the next arrival, lived on the top floor. The second floor housed the animals. On the street level were numerous carriages opened and closed, awaiting the summons of the owners to banquet, ball or burial.

A Gothic arch spread high and wide across three-quarters of the front; a small ordinary door was squeezed in at one side. Through the first impressive portals pranced the chestnut darlings of the rich, coats brushed to a luster, hoofs blackened and polished. Liveried coachmen perched upon the seat of the delicate carriage might well have been made of wood. Through the narrow side gate flowed the life of the family, their bundles and friends.

Should the stalls be occupied, there would be no fun today. If the horses were elsewhere earning their oats, we might jump in the hayloft, play hide-and-seek in the dark corners of the harness closet, race up and down the ramps and prance between the carriage shafts like the best-trained of quadrupeds. Our liking for our playmates who dwelt there was not lessened by the privilege which knowing them entailed.

I wonder. Did Queenie and Prince, Jerry and Beauty, upon our return, resent our intrusion, much as the Three Bears when they discovered the use of their chairs and bowls by Goldilocks?

The Sea

Each year when vacation securely locked the doors of schools an excursion was in order. A sizzling July morning found a group of neighbors burdened with blankets, bathing suits and boxes of lunch climbing the narrow stairway to the "el".

Via this means of transit the first half of the trip took us to City Hall. As we were transported through the lower sections of the metropolis, children with arms outspread on car windowsills watched the houses whirling by and received an introduction to some of life's less pleasant phases seen without.

At Brooklyn Bridge, mothers clutched the sticky hands of children and transferred the group from train to train. Barely had the last empty seat been filled when several discoveries were made. A doll and pocketbook were missing and little Tommy was not with us anymore. With one accord we rose to search. Tommy, discovered standing on the platform, his finger in his mouth and weeping copious tears, assumed a new importance, since his absence had the power to stay the whole excursion. The other errors were beyond correction. Again we took our seats. The snake-like string of cars pulled out and meandered through the various parts of Brooklyn and Flatbush, as though uncertain of their destination, finally pulling to a standstill not far from Luna Park.

Car sickness and excitement were by this time accounting for many throbbing heads. Grown-ups, too, were beginning to question the wisdom of the trip and to wonder who had first suggested it. The mingled scents of roasted peanuts, sawdust, corn cooking, monkeys, and the sea came to meet us. Vendors' shrill whistles, hecklers calling, carousel music, the splashing of the waves bade us hurry.

Through the hot streets of Coney Island to the still hotter sands the party wound its way. At last, the first sight of the water! An unoccupied tent was soon captured and filled with our possessions. Blankets, stretched from center pole to sides, formed individual compartments in which each child disrobed and dressed for bathing.

We raced each other to the shore as if the ocean were about to pull away. A few hesitant footsteps with soapy foam licking our ankles. Cold. Cold. Icy cold! A few shivering dips and we were really wet all over.

As though from earth's distant inlets, strange herbs had been gathered and brewed beneath the sun into a healing infusion, the ocean now drenched our bodies with its life-giving waters. Who can explain this mysterious gift of the sea?

With luncheon spread out upon a checkered cloth, the last sandwich unwrapped, the last ripe tomato peeled, a summons was sent out for all hungry members to report. No sooner had we gathered round the fringes of the cloth, our appetites whetted to a razor's sharpness, than some passerby would cast a pail of sand close enough to cover exposed morsel with grit.

Sand castles were built, holes dug, shells gathered to take home, numerous dips made into the waves, a constant bronzing took place beneath the sun. So the day passed. At sunset we were no longer the wan creatures who had set out that morning, but instead a tribe of husky, reddened warriors.

When evening came, against the darkening sky, Steeplechase and Dreamland flung their strings of lighted pearls, competing with the crescent moon hung low above the sea.

How grand had been the day! How lovely was the night! But, oh, the price we paid was high. Most of us were restored to normal by a rest of several days in bed: sunburns, upset stomachs, swollen tired feet our memoirs. And yet, we'd like to go again.

Temptation

Who, living in that era, could remain long unaware of that institution known as the corner saloon? Here it squatted, two-sided, with the eye of one window looking west on East 70th Street and the other watching South on the Avenue as if fearful lest the housewives of the section descend upon it in wrath.

Its swinging doors were indeed functional. Deep scroll carvings shortened them at top and bottom, allowing plenty of air and light to enter the dark and questionable cavern beyond. Yet the opaque quality of the wood so concealed the customers within that nothing was visible except legs, in their usual inoffensive activity of standing. The absence of locks or handles made egress a simple matter, too, for one whose brain might not at the moment be functioning to full capacity. Swinging freely back into position of themselves, the wooden panels allowed the departing guest to leave in haste, wiping his moustache with the back of his hand, his mind innocent of any plan for closing the doors behind him. (With what welcome, indeed, would he be received back into the bosom of his family?)

This front entrance, all but reeking of brimstone and sulfur, was considered the first step in the downward descent which would eventually lead to an uncomfortable and fiery hereafter. Mrs. X., whose husband was known throughout the neighborhood as a regular patron, was looked upon coldly and with lifted eyebrows. Children passing by walked with averted eyes and kept close to the curb, thus putting all possible distance between themselves and contamination.

Yet, illogical though it was, Mrs. Z. might with impunity stand upon the threshold of the side, or "Ladies", entrance, ringing the bell and holding a black cotton bag tightly by its drawstrings and partially hidden in the folds of her full skirt. A portly bartender with white towel draped crosswise over his broad stomach answered the summons. Admitted into the small vestibule, the lady slipped the cotton casing from a tin beer can. A few words were softly murmured; several coins changed hands. The can disappeared into the inner region and returned shortly, its sides beaded with sweat, its character forever sullied. It was again encased in the black bag. The gentleman bowed, thus concluding the transaction. Mrs. Z. departed, flaunting the perky little feather of her hat in a most righteous manner and smoothing the pleats of her skirt with a nicely-gloved hand. Nor did she forget, in passing the swinging doors, to cast a look of withering scorn at the standing legs whose owners were, no doubt, engaged in the dastardly act of quaffing a glass or two of beer beyond the range of vision.

Enchanted Evening

Leaden skies brought swift ending to a gray afternoon. A sudden chill penetrated deep into one's bones. The scent of snow was in the air.

By the time supper was over, the first spitting flakes of the season were tapping at the windowpane. This was the signal! By long-standing agreement, Helen and I, each in her own house, prepared for "The Great Adventure".

Long, inner drawers, always worn to the ankles in winter and covered by thick black stockings, were now encased in padded leggings, the latter buttoned up the sides and slipped over shoes and rubbers. Wooly hat, scarf, mittens, sweater, a blue chinchilla coat lined with red flannel were added and the squirming creature within was ready to play with whatever breath and movement might be possible beneath such armor. Out we went, like two bullets released from opposing batteries, out into the cold darkness, with the tingling touch of snowflakes on our cheeks—to meet beneath the great iron clock which stood towering high above the jeweler's shop, halfway between our two houses.

The street was deserted. Together, we ran around the block, skidding, sliding, kicking up the soft fluff. In a few hours, the new-fallen snow would lie like whipped cream, thickly covering sidewalk and door post, stairway and tree trunk, in the rich darkness of a winter's night.

Silence and softness and whiteness were still untouched by footprint or shovel. Diamond-dust sparkled in the blue and orange flame of lamp posts! Diamond-dust, strewn freely for rich and poor alike, the beautiful gift of Jack Frost.

Noel

But topping all other events, and mounting in an ever-rising crescendo, came Christmas. Floated in on a note of tingling expectation, and scarcely pronounced as other sounds were, this single word was sufficient to start in motion an overwhelming torrent of physical and emotional activity.

The first warning usually came in the form of a tiny sound breaking in upon the quiet of a gray November afternoon when the family would be engaged in reading the Sunday papers or in taking after-dinner naps. A light tapping on the dining room door—ever so faint—repeated several times, had the effect of an electric current upon all youngsters present. The elder would lay aside the paper, cock aside an ear in that direction, place a finger on lips and nod wisely in confirmation. Of course! It had been Santa Claus listening in outside, having come around for an early check on good and bad children. If the slightest doubt remained, a dash into the outer halls and a futile search through them must convince one that no other than that august presence had been there but a minute before. The wheels had been set in motion, the spell woven.

Not until many years later did a growing mind associate with these early tappings a visit from an uncle which always seemed to have occurred about a half-hour after the excitement had subsided.

Next in logical sequence, came the evening shopping trip. From its resting place in the closet emerged a brown leather traveling bag. A trolley ride brought mother, aunt and myself to a large department store, crowded and gaily decorated. Here I was led to some innocuous spot (such as the stocking counter) and kept there by one watchful relative while the other took the brown bag and vanished, in a most disconcerting way, amid the maze of counters and shoppers. After a brief wait, the shopper's reappearance brought some little ray of hope, enhanced by the knowing looks exchanged by the grown-ups and the twinkles in their eyes. But hope had been raised only to be dashed to the ground. The adults would trade places, and I again would have to wait quietly—perhaps now at the stationery counter—while the other took a turn shopping.

Upon testing its weight, I did, however, note with satisfaction that after each voyage the leather bag would have become slightly heavier. Towards the end of the evening, too, its sides began to strain over bulges which I patted speculatively. As a grand finale, we would climb upon high stools to sip beef tea or hot chocolate. I kept my eye on the luggage tucked beneath the counter at our feet, now and then giving it a secret little kick in the hope that the clasps and lock which were apparently ready to burst open would do just that and reveal at least some of the tantalizing contents.

A much simpler approach, of course, would have been to just leave me at home. But this I could never endure—each tiny ounce of anticipated joy must be savored. My wheedling and coaxing always won out. I was taken along, even though my presence complicated matters.

For a long while, the packages found beneath the tree and the contents of the shopping bag were two distinct and separate phases of the Christmas episode. Just when, in the blur of association, they merged into one and the same thing, I do not know.

About this time each year, a hall bedroom which was not in use suddenly became forbidden territory: "Santa's Workshop". Into it the brown bag disappeared after its shopping tour. The door remained locked till after Christmas, yet activity was certainly going on! A sound of movement could be heard whenever some grown-up remained closeted within. A strange odor of paint seemed to drift from the keyhole, too. And, coincident with these events, familiar objects began to disappear. Jenny, my rag doll with the tin head, just couldn't be found in any of the usual places. When it was time to put the bisque doll, Pinky, to bed, no carriage was there to cradle her. Even my little red rocking chair was missing. Puzzling and strange! Very, very strange—like so many things that were happening these last few weeks.

Slowly the days passed (far, far too slowly for fast-beating little hearts). Slowly, too, but surely, additional signs began to appear. Rehearsals started for the Christmas play; and, finally, the play itself was presented, when familiar classmates, no more angelic than oneself, took on a strange, unearthly appearance. Heads ordinarily flanked by stringy locks were now surrounded by bobbing curls. Grimy, fidgety hands shone with cleanliness and reposed (for a while, at least) in graceful positions. Plaid skirts and middy blouses were exchanged for flowing white cheesecloth robes and the trembling creatures within fairly staggered beneath glistening wings edged with tinsel, the hallmark of celestial inhabitants.

Packages from distant friends began to arrive. The turkey must be carefully selected and its necklace of fresh cranberries strung. Nor could the steaming of the plum pudding be omitted. Holly wreaths appeared in windows. The pungent scents of fir and pine permeated vegetable stores, schools, churches. Tall forests seemed to spring up out of familiar sidewalks as the trees stood awaiting the selection of buyers. Oh, joy unbearable! The day was nearly here! Could one possibly wait any longer?

At last! Christmas Eve, at twilight, became unlike any other day the year round. Each task was performed with finesse and delight. Long stockings fastened above the kitchen stove were tested for security, a tall white taper was lighted and placed in a window, the sky above was scanned for any trace of fast-travelling reindeer, the dining room was cleared as if for Sunday. All was now ready, not a detail forgotten.

Brushed and scrubbed to a painful luster, I was popped into flannelette nighties and tucked into bed early—fiercely determined not to close an eye the whole night long. I intended only to wait and listen and watch. A long silence followed. Someone cautiously peeped in at the bedroom door. Then there were footsteps; hurried, yet soft, continuous sounds kept up beyond a drowsy consciousness. I remembered I was going to stay awake. To wait…to listen…

My eyes opened slowly. Darkness. Silence. Suddenly I realized that hours had passed. I leaped out of bed and dashed to the kitchen. The stockings bulged queerly. Oh, joyful day! It was true. Santa had come! I rushed into the parlor. A softly shimmering tree towered there, and piles and piles of packages rested beneath it. There was the missing Jenny, a rosy glow upon her freshly painted cheeks, a new set of rice teeth showing between her parted lips, her tin head sewn securely back upon a body newly dressed in gingham. And Pinky, a black curly wig replacing her worn golden curls, peeped out from her carriage, now adorned with luxurious robe and pillows of satin. How lovely my little red rocker was, now with a cane seat and red leather back reinforcing its aging frame! (Would that we, too, might be withdrawn to "Santa's Workshop" for rejuvenation when time and cares have had their way with us!)

It must have been all of five a.m., but the whole family was astir. A hurried dressing and a hasty exit through the heavily locked outer doors brought us into the silent street. Night was still with us, but a chilly dawn already streaked the east with blood-red streamers promising snow.

At church the statues of the shepherds knelt motionless before the manger, fir trees banked around them. The first Mass began. Deep, deep, deep into the hearts of young and old sank the profound peace that is Christmas.

Afterward, we returned home to the color and excitement, the tinsel and glitter, the gifts and the goodies. We could barely touch our favorite breakfast of sausages and pancakes swimming in syrup and butter. After what seemed like an eternity we left the dishes unwashed and hurried into the parlor.

The long-awaited moment was here. From stuffed stockings tumbled oranges, nuts, small toys, and notions. Faster, faster flew the ribbons, tags, and papers until the very furniture was snowed in under a blizzard fantastic: dolls, paint sets, candies, wooly nighties, a white fur muff and scarf, perfumes, handkerchiefs, pocketbook and cash, knitted slippers, skates, games, sweaters, gloves, a brown teddy bear, a camera…

For a fortnight afterward the kitchen would lose its prestige, the parlor having been transformed into a fairyland. Here I would spend long hours beneath the spreading branches, reading books, playing games with friends, tasting nuts and sweetmeats, and examining my gifts again and again.

But on Christmas night, an enchanted circle formed around the tree: the nearest and dearest, the thoughtful and laughing, the youngsters, the aging. Of the latter, each, in her heart, was remembering other Christmases. Each, in the wavering shadows, seeking: seeking, as though on this night of nights, drawn from afar by the magnet of love, the presences missed might return to hover unseen in the glow of the tree.

With what care had the candles been set that no flame might reach a branch! One by one they were lighted, a sheet spread beneath catching the wax as it dripped. Just as a precaution, a filled water pail, damp cloths and a broom were kept nearby. How red the isinglass glowed in the rounded sides of the stove! Hot toddies and caraway cakes were passed out, with hot lemonade being the beverage of choice for the children. Someone began to softly hum a carol. Soon everyone was singing; before the candles had burnt down to their holders, a full chorus enveloped the tree.

The hands of the clock pointed to ten. It was over! But each night till after the New Year, the same routine would be followed with one group of guests or another. Yet, it would not be quite the same. Only Christmas touches the heart.

The Earth Turns

After the holidays, winter, bitter cold, sheathed in ice, settled upon us. Before one blanket of snow could be banked at the curb, the wind swirling down from the north buried the city again under fresh layers of white. Men fought the storm with shovel and broom while the soft deluge descended. Children ploughed their way to school waist deep in the drifts.

Sometimes tandems of four, straining against the gale, tugged heavy coal trucks through ruts. Often the wheels, embedded in snow to the hub, refused to turn. Drivers climbed down from their seats to shove with the beasts, lashing, the while, the steaming flanks of the horses who lurched in vain. In mute pity children stood watching the sad plight of the servants of man. A truck stranded thus in the morning might be left all day long in the blizzard, the horses covered with blankets, their heads bending low against the sharp wind, icicles hanging from nostrils and bits and forelocks. Then, just before dusk, their poor backs would be stripped again for the whip and more horses added. If this last effort failed, almost too frozen to move, and sore from their beatings, the weary beasts would be unhitched and led back to the stalls while the truck was left blocking the street.

A cold spell, a slight thaw, a storm. So it continued for weeks at a time. One forgot there were sidewalks beneath the uneven paths through the snow. Milk was delivered frozen up and out through the neck of the bottle. Sometimes, with the cold of evening increasing, a match applied to the gas jet brought forth no answering "pop". The gasoline had frozen, brining annoyance to the grown-ups and pleasure to myself, in my innocence excited at any change in routine.

Here and there we placed stub ends of candles, set into cups and secured in their own hot drippings, in the room. Gigantic shadows leapt to the walls, no longer fashioned of plaster but transformed by a touch of imagination into the logs of a cabin. I imagined gusts of snow beating against the window were but the brushing of an Indian head dress. Stew ladled into bowls became the finest of bear meat, caught last week in the forest. How much more exciting to live so in the pages of history! Of course, imagination unbridled may travel too far, so that my spine tingled with draughts from the dark hallway, seemingly threatened as much by redskins as by cold.

How dark the street seemed without its accustomed lamplight! How dim the flicker of flame seen in the houses of neighbors! How short the evening!

On just such a night, then, settled deep under the quilts, I might be dreamily watching the smoke from an extinguished candle as it rose in eerie pattern against the white blur of the window, when unexpected, unwanted, a high wail of terror pierced the air. The signal of fire! Had someone tipped over a candle? Or moved it too near a curtain? Whose house was in danger?

We leapt out of bed. Nearer and louder grew the shrill note of warning. Our noses pressed flat against every pane, our shivering bodies stood rigid while all eyes marked the progress of the flaming chariot. Closer and closer it came, three beautiful beasts, as though winged, bearing it on. The sparks struck from the tracks by their hoofs were as bright as the fiery volcano pouring out of the smoke stack. Oh, may they not slip, nor dash against one of the pillars supporting the el! Now they had passed and were turning into a side street. A dull red glow and a puffing of smoke above roof tops marked the place of disaster.

The winter was hard. It was brutal; but color, emotion and movement punctuated the nights and the days.

Breaking the monotony of the stinging March winds, came nights when milder weather sent rivers of slush rushing down the gutters and dense murky fog drifting overhead.

Then the foghorns, mournful and constant, created an uneasy, tension within the house. Lifting her eyes from the darning, my grandmother stirred restlessly in her chair. How often, a half century before, had she listened to these same minor notes playing over the New Bedford hillside? How often had they guided into harbor my grandfather's whaling vessel returning from the churning waters of distant seas? In those earlier days foghorns were harbingers of news—of whale oil taken and scrimshaw carved, of profits made and seamen lost. Now they denoted the restless stirring of winter which presages the coming of spring.

Little by little the weather relented. Snow had withdrawn from its last shaded holdout. Tiny green blades pierced the sod in the iron-grilled garden nearby. April was gentle and warm. At the wide-open windows white curtains puffed back into rooms where the clean smell of suds and hot iron on clothing persisted.

Wherever I turned, signs of young life appeared. In store window corrals, fluffy yellow chicks, and soft brown bunnies, gazed out in innocent wonder upon a world they were so soon to leave. From flower shop doorways, tall lilies nodded to the crowds. The organ-grinder's monkey arrayed in gay-colored pants and bolero, danced in dappled sunshine at the curb. No smug satisfaction of befurbelowed matron as she joined the Easter parade could match the honest pride of my Molly marching her freshly-preened kittens across the alley way. The world was alive to the touch of spring.

Yet it was in the open, in garden and park and grassplot, wherever a patch of black earth appeared, that life was most abundant. Impossible, after the turmoil of winter, the storm's desolation, the killing frost! Impossible, truly! But, look—cracking the surface of the earth, setting at naught the cold death of winter, the flowers were rising: fragile, undaunted, defiant of weather and man, with a force and a sureness astounding.

Here sturdy hyacinths bordered a path; there, clustering daffodils nodded in the breeze; beneath trees, wild violets hid in the grass. Like the insistent words of a love song, repeated again and again, the flowers were telling a story. Clothed in textures of rarest beauty, in regal purples and gold, in delicate pink and blue, the flowers were rising again in a response to a Summons Divine.

Spring slipped gently into summer.

Could anything ever be more restful than one of those summers filled with day dreams and languid activity carried on beneath friendly tree or hospitable awning?

On Sundays while the family sat chatting leisurely after dinner, I was dispatched, hugging a shining dish of pressed glass, to the ice-cream store nearby. Lucky indeed was she who found a vacant place, for here, perched on high stools, for all the world like a flock of crows on a fence, and leaning half-way across the marble counter in impatient expectancy, were to be found most of the children in the neighborhood. In unison, their heads followed the scoop on its trips to right and left as it flashed, now poised above mysterious icy depths, now plunging downward to reappear in a second filled to overflowing. How horrible the thought that perhaps the stock may be depleted before my turn arrived!

At long last I was waited upon. As the coin of barter offered jumped in value from a nickel to a dime and, finally, to a quarter, with each raise a goodly new portion of cream was dug out of the deep bin and slapped into the waiting dish. Each extra nickel warranted, too, the addition of a new flavor. By the time a quarter's worth had been compiled and covered with a piece of white paper, there was sufficient ice cream to feed a whole family and colors enough to inspire the making of a patchwork quilt.

Pegasus, on his winged course, never traversed the airy by-ways with greater speed than did I with this precious burden. Even in flight, the paper was lifted again and again so that a surreptitious thrust might catch some of the oozing luscious contents.

The sun crossed and recrossed the heavens. Sweltering days passed. Nothing hurried.

Old Dobbin of snow-storm fame, wearing his straw hat at a rakish angle and flickering his protruding ears, cast an indolent eye over the top of the horse trough. Dobbin drank long, with a grateful nod now and then in the direction of the driver who had called a halt in the shade and let down the reigns. The, with a devil-may-care shake of his dripping head, he shambled off again refreshed, but with sweat still trickling down his heaving sides, his legs stewing in the heat waves that rose from the pavement.

Open trolley cars rattled along the avenues, the conductors swinging from seat to seat in the pursuit of fare collection much as monkeys swing on the bars at the zoo.

Like bees unwilling to leave one drop of sweetness ungarnered, we gathered again as the long evening faded. A request for a chocolate soda (purposely made in the presence of my friends) could scarcely be refused. The nickel was handsomely given and the troupe clattered off to the ice-cream parlor for a long, noisy session.

And now the last few cherished moments of freedom approached. On the soft darkness of the night, thin gray-blue scrolls were traced by smoke from Chinese punk sticks. Their glowing red tips and aroma of sandalwood together with the flash and snap-snap of cap sticks and the flare of hissing sparklers provided a dramatic finish to the fullness of the day.

I said goodnight and reluctantly departed, trailing incense and clasping to my heart the fabrics with which to weave dreams.

When the first cool breeze whispered to the summer that its hours were numbered, people bestirred themselves. Feverish activity replaced the lackadaisical life of the last few months. Apparently, everyone had suddenly remembered some urgent business without the completion of which the world might stop turning.

School clothes were fitted, lengthened and aired. With tempting arrays of needed supplies shopkeepers lured unwary youngsters from their play. The speed and delight with which the children bought might lead one to believe that school was a fascinating place—that is, if one were only six and had not been there before. Pads and blankbooks were selected. School bags woven of hemp were fitted out with rulers, erasers, crayons, sharpeners. No end of pencils were crammed into black lacquered boxes, the key so securely stowed away that it might never again be found. Was ever such eagerness for the tools of learning before displayed? What masterful compositions, what accurately solved problems, how many colored maps and correctly listed dates would appear on these pages? With a flourish and vigor would the first week's assignments be done, deceiving incredulous teachers into believing that the millennium had come and that last year's pupils had changed into scholars during the summer vacation. Little need they wonder at the miracle, for the first burst of enthusiasm would soon peter out and dwindle into a negligible and unwilling effort, leaving teacher and pupil in their age-old status quo.

Of more enduring nature was the activity of my mother and Aunt Mary. Awnings, beginning to rattle in the brisk wind, were removed; windows polished, woodwork scrubbed. As the covers were peeled off, I remembered having seen the red plush furniture before. The figured carpet looked familiar, too. What wonders were worked on the wide gilt picture frame by a mere coating of powdered gold leaf and banana oil! If no poles were available, the lace curtains could stand of themselves like screens before the windows, such had been their starching.

Sunlight entering the kitchen picked up the deep clear purple of jelly and silhouetted the sticks of cinnamon imprisoned within each glass. At closed windows, the mingled odors of grapes and spices battled in vain to escape. Then, captured, they remained indoors to tantalize and goad small children into pilfering a spoonful—or two—or a jar.

With the lengthening of chilly nights, my old friend the rounded stove stepped out of the closet and backed itself up against the parlor wall. Here on a tin mat it would sit for many a day, whistling contentedly while draughts sucked smoke through the long black pipe. How good to note again the scent of burning wood.

Without, the temperature was dropping. The sighing winds were housecleaning, too, dusting the branches of trees. Yellow leaves, gliding to earth, turned to wave farewell to gray skies.

The house withdrew into itself as if unwilling to be friends with winter again. Let the cold and the winds have their way. Within, coziness awaited. Fires glowed red; shades were drawn; supper simmered on the stove. Let the family draw close, for there was more to be shared than the simple food before us. Meat and bread would nourish for today and tomorrow but the spirit of home sustains the heart for a lifetime.

Gilded Cages

On rare occasions, high adventure in the form of a trip downtown beckoned. Dull and drab enough in its way, the day was always to be endured for the sake of its climax. Then, tired after endless hours of shopping, led by the hand, I was conducted into the heart of a large department store and seated upon a chair whose fragile legs of twisted wire seemed to be made of some magical substance. For no sooner had I been seated upon it, drawn a breath and turned to glance around, than all weariness slipped away.

Here blossomed an interior fairyland in which the senses might revel. Ears listened to the musical dripping and splashing of a huge center fountain whose myriad fine jets, illuminated by sparkling lights, played out in all directions and sprinkled the ferns planted around.

Encircling the ferns, a great circular counter displayed unbelievable amounts of candy upon which eyes might feast and mind speculate while the sweet, tart and creamy flavor of a strawberry soda quenched one's thirst.

As if this were not enough stimulation, the walls of this glittering spot offered still another thrill. For they had been fashioned of tall metal shafts in which, trapped in open-work gilded cages, like animals in a zoo, solemn groups of humanity rose and descended precariously, in response to the pull of slow-moving cables, and much to the fascinated delight of those safely sipping refreshments below. (No wonder the slogan, "Meet me at the fountain!") Truly, it was too much! Heavy lids began to droop; my head to nod, my shoulder to ache for the softness of my own little pillow at home.

Departure

Then came years when mid-June found us requesting Adams Express Company to call for luggage and deliver it to Westhampton. Several well-to-do customers had houses on the ocean front there or in towns nearby. The dressmaking trade followed.

Our summer dwelling was not in the fashionable section but about a mile inland from the shore. An elderly couple rented us their furnished farmhouse and moved, for the summer, into an older homestead on the same large property. Advantages derived from this triangular arrangement were not to be denied. For us, there was a continued source of income and a summer in the country; for the customers, the close proximity of Aunt Mary's skillful hands.

What a to-do of preparation took place! Trunk after trunk was filled with linens and clothes, the overflow being packed into a huge straw hamper, its lid bound tight with ropes. Windows were closed; awnings lowered and tied, so that metal frames would not puncture panes nor cloth rip.

Just before the apartment was left in semi-darkness with padlocked doors, at the very last moment, the birdcage was lifted from its bracket and protected with a dark cloth to shield the sensitive little inmate from the terrors of the journey. How thoroughly dismayed was Molly the cat by all this confusion in her usually tranquil world! How shattered her feline dignity when hastily lifted by the scruff of the neck and stuffed into a hat box punctured with air holes. Nor could the affront be easily dismissed because the box contained a bit of meat and marrow bone for consolation in her seclusion.

Last minute pick-ups and lunch were wrapped; a collection of umbrellas tied together. This assortment of possessions was then distributed among the members of the family. Finally—we were ready to leave!

A trolley approached gaily down the avenue, lurching from side to side. The motorman twirled the metal handle of his controls with finesse born of long experience. His world was rosy; the coast was clear. He whistled his favorite tune. A sudden frown appeared, a furrow deepening between his eyes; the ditty ended on a high, unfinished note. Our party had been spotted. The trolley slowed and came grudgingly to a halt. It it was to continue on its way, there was nothing for the motorman and conductor to do but assist in hoisting aboard our group of four, with its bundles and live-stock.

After our arrival at Pennsylvania station, there was much nervous checking of tickets, timetables, etc. and numerous trips to the water fountain before we finally struggled through the opened gates and down the ramp to sink at last onto the red plush cushions of a waiting train. With many a groan and heave, the family tree had been uprooted for transplanting to another soil.

Certainly a summer on Long Island could not warrant such magnitude of preparation. Central Africa or the mountains of Tibet must be the fitting destination!

Arrival

Before seven that evening, the conductor walking through the cars announced "Westhampton! Westhampton!" The brakes uttered a little screech; the coaches shuddered. A footstool placed beneath the lowest step helped us to alight.

Backed against the platform were several carriages, their lamps already lighted. One or two cumbersome autos of early vintage stood awkwardly nearby. The public coach with luggage rack on top and drawn by two horses waited for those passengers who would not be met by private conveyance. Walking towards us, his rough, brown hand extended, a suit coat covering his work shirt and overalls out of respect for our arrival, came Mr. R.. The welcome in his bright blue eyes he did not need to voice.

The train had more important business to attend to and would not be bothered by these trifles. With a shrill whistle and a few snorts it waved its plume of gray and salmon-colored smoke and disappeared around the bend. It would return for us in the fall.

The autos had lumbered off; the last of the carriages was following in clouds of dust. We looked around. This was, indeed, a different world, and one less ancient and less worn. Across the nearby fields a counterpane of daisies had been thrown. Neither day nor night could claim the moment for its own, and silence was a part of everything.

Jed the horse, his mind on oats and hay, stamped impatiently and neighed. We filled the carriage to capacity. The reins were lightly slapped across his haunches; the harness strained, the carriage creaked and moved. Our way led over fields and through the woods where hazel branches reached in to touch us on the arm. At the cemetery gate, tall cypresses eyed our passing with suspicion while they stood guarding ancient tombstones sagging and awry. Wheels ground the sandy soil. Jed trotted on. Long shadows stretched across the pond and crickets chanted in the lonely evening.

How friendly was the news of ten long months concisely reported as we rode! The winter had been long and hard. Old Mr. Smith had passed away in March. The Browns' son was home from his first year at college. Our garden was all planted. Mary Ann had eloped with the grocery boy. There was a new dog on the farm this year.

Jed felt the load heavy as he brought us over the crest of the hill onto Old Country Road. There was the hedge still framing the low, white farmhouse; lights shone from the windows, the smoke of a wood fire rising from the chimney. Beneath the grape arbor, her old face creased into a thousand lines of joy, her arms outstretched to greet us, stood "Aunt" Ida.

What a furious barking and jumping took place! Gyp, the new water spaniel, resented these strangers, while Rod circled the carriage waving his tail at the smell of old friends. Tommy Cat sat in his favorite spot atop the covered rain barrel, as though he had not left it since September. His plume-like tail swayed gently while he carelessly scrubbed his whiskers with his paw. Now he stopped, paw arrested in mid-air, eyes cool with recognition as Molly jumped from her hat box and stretched luxuriously before him. Roddie, too, brushed gallantly against her to renew last summer's friendship. But Gyp had to be chastised for ungentlemanly snarls.

The oak tree spread its arms above; the night chill deepened as we stood outside the kitchen door. Here we belonged. This was our "second home".

Salt of the Earth

Supper waited. We must sit down at once. The hanging lamp stirred slightly in the breeze, and cast a mellow glow that flowed around the table to bind us close together.

Our hostess, swathed in blue checked apron and chatting briskly

all the while, served her country fare——each dish a product of the

farm. A fowl, pot-roasted brown and tender and swimming in a soup

tureen of gravy, was placed upon the trivet. Covered vegetable

dishes kept hot the "parsley potatoes", steamed dried corn, and new

peas plump and green. Jellies and pickles set about in dishes spiced

the meal. From the oven came a loaf of well-browned bread. A butter

pat of roses passed from place to place. Strawberries picked that

afternoon and rich with cream rounded out the feast.

pat of roses passed from place to place. Strawberries picked that

afternoon and rich with cream rounded out the feast.

Nor had the pantry been neglected. Later, when aunt Ida had gone home, the items needed for next morning's breakfast were discovered ready on its shelves.

Rough and hard might be the hands that set the table; plain and out-of-date, the clothes. The speech was marked by local twang and phrasing. But none surpassed and few could equal hearts like these in warmth and kindliness of feeling. These were the gentlefolk of earth.

It had been a strenuous day, but one with a lovely ending. At last we climbed the narrow stairs. The rooms above were cool and filled with honeysuckle scent. Rag rugs were scattered on the floors. Each bed was covered with a patchwork quilt, and sheets and pillowcases had come from chests where basil leaf had left its fragrance. We turned the oil lamp low and blew it out.

Inspection

A cock crowing announced the coming of morning. The eastern sky grew gray, then white. Pink clouds appeared above the flat horizon. Then, in a burst of flame-red glory, the sun was fully up. The day would be extremely hot.

How clear and fresh the sunlight, reflected in every trembling drop of dew! How sweet the air blowing through the kitchen door! Its gray-painted walls, subdued and restful, tempted one to linger over breakfast. But who would tarry with the whole world waiting just outside?

Milking time was over and cows were being watered and led to and fro for staking in green pasture. The barn, being of major importance, merited my first attention. Yes, it was very much the same. Each horse still had his own large stall. Jed munched his feed contentedly, oblivious of my visit. Light brown in color, of sturdy build and tenuous of muscle, he drew the heaviest of loads. At my approach, Dick rolled his eyes, laid back his ears and moved uneasily. Thin and black, high-strung and nervous, he responded well to the hand of a kind and firm master, but should never be harnessed for a woman's driving. Ah, Jerry! My favorite, stable and even-tempered, put down his head to have the white star on his forehead rubbed. Hay-wagon shaft, carriage harness or plowshare were all the same to him as long as he was moving. Jerry asked no favors but his food and water. Sugar, and apple, or fresh grass were always lifted from my palm with utmost delicacy and the faintest tickling touch of his soft nuzzle. We understood each other very well.

The two cats, now rubbing their sides against the stalls, had accompanied me ostensibly motivated by pure friendship, but really with an eye to forgotten milk pans or to any mouse that might stick its silly head out of the hayloft to see what all this commotion was about.

Outside in the yard, the poultry roamed, each family a separate social unit. The Rhode Island Red and her nearly full-grown brood chose the flower bed and scrutinized the stalks and leaves for bugs. The Plymouth Rock, heavy and overbearing, her chicks half-grown, would hold the fort right here in the grass plot! Let other families move about! The Leghorn, light and graceful, with tiny, fluffy offspring, withdrew into seclusion. Up and down the garden rows they pecked their way, the babies chirping shrilly. Each brood received its morning lesson from the mother hen. This was the better way to scratch. These were the choicest morsels. A reluctant worm might be induced to leave his ground hole thus. Dogs need not be avoided, but cats were temperamental. One never knew; it was best to keep out of their way, especially when chicks were very young. This was the water pan. The head was lifted, so, in drinking.

A family of ducks passed, too, waddling heavily from side to side. The roosters strode alone, with plumy tails and most insufferable airs.

Only the bull, of all the animals, remained in isolation, tethered by a lengthy rope within a barbed-wire fenced. With him I had no dealings, nor did I offer stalks of corn. I kept my distance, too.

Last to be visited, and only for a few brief minutes, were the pigs. With tails curled to perfection and little prancing hooves, the young ones came to meet me at the fence and squealed loudly for corn.

The sun was high. The morning was far spent, with little left to see but the flowers. Across the flat top of the hedge the spider hopefully spun his web. Within the yard were rows of dahlias and gladioli not yet come to bloom. Upon a wire screen climbed tall sweet peas of every hue, both pale and bright, that could be thought of. A butter tub propped on a bed of rocks held cornflowers of the deepest blue.

Listen! Across the acres between the other house and ours, deep and mellow, came the steady ringing of a monster cow bell—the call for all hired men to wash and come for lunch. It marked, unconsciously, in a slow and measured rhythm, the tempo followed on the farm by man and beast.

Sanctuary

Early afternoon was even warmer than morning. The buzzing of "hot weather birds" increased the sense of heat. Naked fields vibrated with it. Corn loved this weather. The stalks stretched in exultation and seemed to grow taller by the minute. The shiny blades waved and gloated in the scorching sun.

Row after row led to the edge of shady woodland, a sanctuary where all things grew wild and good. Here socks and shoes were done away with. Cool shallow water running swiftly over stones soothed my burning feet. I splashed my face, a free young thing among free young things. Moss formed a spongy bed on which to lie and view the passing clouds above the topmost bow. All around, I had a feeling, little eyes were watching to see if it were friend or foe who lingered, uninvited, in their parlor. The brook whispered a tune, accompanied by the rustling of the silken garments of the trees. Nature guarded jealously her treasures. To those alone who would sit down and visit with her were they shown. Here, if one waited long enough, one might discover the universe anew and even find one's self.

Here also was nature's candy counter. Fragrant mint grew at the water's edge. Dark green leaves, protecting pure white berries, if crushed, would fill the air with the scent of wintergreen. The root of sassafras was good to nibble and young birch bark shoots were delicate in flavor. A tangy gum had oozed from cracks along the trunk of the wild cherry and hardened into lumps for chewing. All of these, since time began, had quenched thirst on a summer's day.

Seated high up in the branches, out of sun and out of sight, I could view the clearing which stretched from one wood to another. Snuggled in between the gardens and the corn fields were eight houses with their barns and sheds. These formed our little world. Here we must live together in harmony, each family distinct, yet each somewhat dependent on the other.