| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/18/2024 Occurred: 3/11/2006 |

Page Views: 3288 | |

| Topics: #EdnaMaeCilwa #EdnaMaeBrown | |||

| My obituary for my mom, Edna Mae Brown Cilwa, who died on March 11, 2006. | |||

My mother, Edna Mae Brown/Cilwa, died March 11, 2006 at 4:15 pm EST of abdominal cancer. She was 93.

Mom was born Edna Mae Brown on June 18th, 1912 in Montclair, New Jersey. That was shortly after the Titanic sank, but Mom always insisted those two events were unrelated. She was the second child of Vernon L. Brown and Mary Virginia Chapman/Brown, but the first, a brother, had been stillborn; so Edna Mae was raised as an only child.

An enterprising youngster, when she was about five years old she found

discarded newspapers and sold them to neighbors for a nickel, explaining that

the funds were for the two orphans and both of them are me.

She attended kindergarten as the First World War raged. A popular ditty at the time went,

I lost my leg in the Army,

I found it in the Navy,

I dipped it in the gravy,

And gave it to the baby.

The kids were all taught the song and made to march around the classroom singing it. After a few choruses the children were told to sit down, but Mom pretended not to hear and sang all the louder. The teacher sent Mom to the principal's office.

Apparently Mom had been there a few times before. When she got there, principal Sister Lucy Agnes was out; so Mom sat herself down in the woman's big, wheeled chair and began rolling around the office, singing at the top of her lungs:

I lost my leg in the Army,

I found it in the Navy,

I dipped it in the gravy,

And gave it to Sister Lucy Agnes!

Of course, at the song's conclusion, you know who was standing at the door, glaring at the youngster…and probably struggling to keep from laughing.

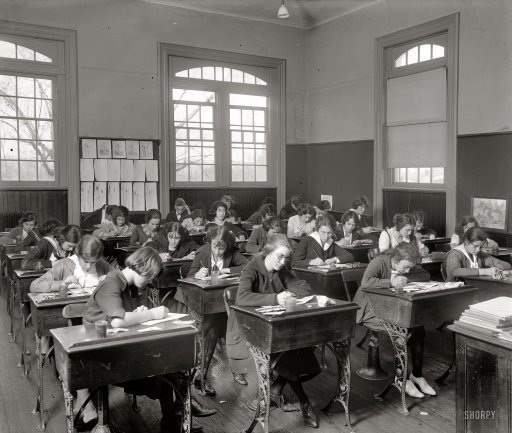

Mom's inventiveness came out a few years later. In fourth or fifth grade, the

kids found innocent fun in stacking their books in front of them, offset to

create the effect of rows of typewriter keys (obviously longing for the eventual

invention of laptop computers). For Mom, this wasn't realistic enough. She

suggested to the kids that they cut out little round letters from paper and

place them on the offset rows, which they did. It worked great, until someone

opened a window and the letters whirled around the room like confetti. It was

Edna Mae's idea!

the kids were quick to point out. Back to Sister Lucy Agnes'

office.

When the Great Depression hit in October of 1929, Mom, at 17, wasn't affected because my grandfather didn't invest in stocks; and, as a successful optometrist with his own office in Bloomfield, didn't have to worry about losing his job. In those days before air conditioning, anyone who could afford it had a country home to retreat to in the worst days of summer. Mom's was in Pawlet, Vermont. However, her father seldom accompanied her and her mother there, remaining in the city to work.

After high school, Mom appeared in plays put on by the Mercier Club, a quasi-religious social organization. It was there she met Lou Nosier, and fell in love. They dated for some time. It was only recently that Mom confessed to my sister why they broke up.

I was a kind of stinker,

she said, referring to a whimsical tendency to

play practical jokes. When Lou came to pick me up for a date, he always gave me

a little kiss. One night when I knew he was coming, I put straight pins between

my lips. They stuck him when he kissed me.

He never trusted her after that, and

stopped taking her out.

She dated other people but could never get him out of her heart. Even after Lou married, Mom wouldn't contact him because she didn't want to risk damaging his marriage—but she still loved him.

Single and in her 20s, Mom and her mother continued to vacation in the summers: in Pawlet, Canada, and Florida.

World War II came. Mom was only four-foot-eight, too short for the Waves and even for Red Cross; so she volunteered for Canteen, feeding soldiers and sailors on leave.

Mom's mother died of diabetes. Her father almost immediately remarried the secretary with whom he'd been working all those summers: Dorothy Weems. If Mom found this to be scandalous, she never said so; and, in fact, she and Mom (who were only 9 years apart in age) became great friends; and she became the woman I knew as Grandma.

At 38 years old, she was still single. She was spending a summer weekend at Cape Cod when one of her two best friends, Norma, introduced her to her new beau, Walter Cilwa. They attended a Halloween party together and by the time the party was over, Mom was smitten. They married when Mom was 39. Fortunately, Norma didn't care.

I was the first child, followed in stair steps by Mary Joan, Louise, and Dorothy Jean. However, Dorothy Jean died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in 1955. Mom was devastated.

Perhaps it was in trying to escape the memory of her lost baby that she convinced my father to move to Vermont, in spite of the fact that there would be no work for him there. She was, however, accustomed to a mother and her children living apart from the working father. So we moved to Victory, Vermont while my dad continued to work in New Jersey, returning home for weekends.

We moved in June. By November, the 400-mile commute seemed to be taking its toll. Dad was exhausted. The local doctor diagnosed high blood pressure, but it was more serious than that. In December, Mom's husband, my father, died of a brain tumor.

Mom tried to make it on Dad's Social Security checks but the house we'd bought was a century old and needed expensive repairs that tore through what money he'd left pretty quickly. She also began to worry that living deep in the woods of Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, with no phone or electricity, might not be the most prudent place for a widow and her three children. In 1961 we moved, with my grandfather, step-grandmother, and great aunt, to another place where she had happy memories: St, Augustine, Florida.

Great-Aunt Edna went into a nursing home pretty quickly. Grandpa died a few years later. After my sisters and I married, Mom and Gramma moved into an apartment. After Gramma died, Mom got her own little bungalow.

When Mom was in her seventies, she visited me in Virginia. We hiked to Mary's Rock near Skyline Drive. It was quite a hike for a woman her age, but she made it. Later, she said whenever things got rough, she'd remind herself she had "survived Mary's rock" and she could survive this.

Ten years later, she could still hike.

Michael

and I took one of his sisters to Sabbaday Falls in New Hampshire. Mom, having scooted ahead of everyone else,

realized she had left the rest of the party behind and scooted back, saying,

Would you like to rest, dears?

much to the annoyance of the younger, but

out-of-breath, members of the party.

She didn't like living alone but had said all her life she didn't want to be

a burden to my children.

Nevertheless, she moved in with my sister Louise

after Louise's older son got married, and began spending summers with me in New

Hampshire. After I met Michael, and he and I moved to Arizona, Mom continued to

spend summers with us. She spent every opportunity walking our local Wal-Mart,

making friends with the greeters and stock boys and cashiers, all of whom knew

her by name and kissed her each day when she arrived.

During her winters in Florida, our other sister Mary Joan drove Mom to and

from Mass each Sunday. One particular day, Mary Joan couldn't pick Mom up

afterwards, and Louise said she would as soon as she was finished with a

patient. You may have to wait a little bit,

Louise cautioned. But it's a nice

day; just have a seat in the park and I'll get you as soon as I can.

Oh, I couldn't!

Mom protested.

Why not?

Louise asked.

Mom looked at her as if she should know. I'm wearing this red dress,

she pointed out. People will think I'm on the make!

Just before Thanksgiving, 2005, Mom developed a severe stomach ailment which was diagnosed as abdominal cancer—the same thing that had killed her father. A minor procedure was performed to open her colon and take a biopsy, but the prognosis wasn't good. The radiation and chemotherapy treatments required to treat such a condition would be fatal to a woman her age and in her condition. She opted for hospice care, which manages pain without trying to cure the patient. In December I flew with her to Florida so she could be cared for by Louise, who is a nurse, and Mary Joan who could watch her when Louise was at work.

The paper typewriter incident of her youth was pretty typical of Mom's

ability to deal with technology. She never did understand the Internet; she

couldn't understand how pictures I had put into my computer at home could be

viewed on a demo computer at a store. As far as I know, she never did retrieve a

voice message on her cell phone. And one day a month before she passed, she got

Louise to put fresh batteries into her TV remote control. After Louise had done

so, Mom turned on the TV, looked at the screen, and said with satisfaction, Ah,

yes. The picture's much clearer.

Goodbye, Mom. I'm sure you have a clear picture now.